Tony Abbott and Bill Shorten are both desperate, for their separate reasons, to get the metadata legislation cleared away this parliamentary fortnight rather than have it hanging until the budget session.

Apart from being under pressure from the police and security agencies for the legislation – which forces communications companies to retain data for two years – the government fears potential problems if the issue drags on. It’s having to make special arrangements for journalists – with more time, other groups (lawyers, clergy) might press claims.

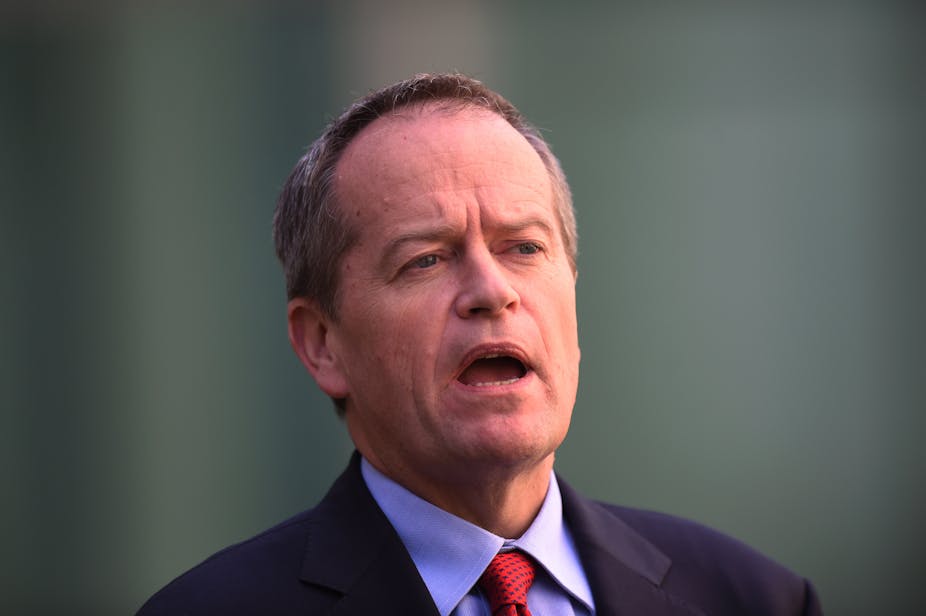

Shorten is anxious to keep bipartisanship on national security; apart from anything else, he doesn’t want to give the government an opportunity to wedge Labor.

So far, Shorten has been remarkably successful in his aim. There has been agreement between the government and Labor on extensive changes to Australia’s national security framework, after the parliamentary committee on intelligence and security thrashed out amendments, which were accepted by the government, allowing the opposition to say it had had influence.

On Tuesday, the Labor caucus voted overwhelmingly to back the metadata legislation, provided the wording of a proposed protection for journalists – that a warrant would be needed to access their metadata for the purpose of identifying a source – was considered satisfactory.

Shorten received the amendment shortly before 5pm. Labor will discuss the detail with the government on Wednesday.

In the caucus debate, which lasted almost an hour, some Labor MPs raised objections to the legislation. The criticisms were both substantive and political – that the accountability and protections did not go far enough, and that “we [Labor] keep digging the government out of its own shambolic mess”.

The situation of journalists – who need to protect confidential sources – was always going to be one of the more difficult points in the legislation.

The parliamentary committee made two recommendations.

It should do a further inquiry, running three months, into “how to deal with the authorisation of a disclosure or use of telecommunications data for the purpose of determining the identity of a journalist’s source”. This inquiry would consult media organisations and look at overseas best practice.

Second, it recommended that when journalists’ data was accessed to identify sources, a copy of the authorisation should be provided to the Ombudsman or Inspector General of Intelligence and Security (depending on the agency doing the accessing), and this also should be passed on to the parliamentary committee.

The second amendment has been accepted. As to the first, the inquiry started and scheduled media organisations to appear on Friday.

Abbott said in a letter to Shorten this week that the government did not believe the additional amendment – the requirement for a warrant – was necessary but would move it “to expedite the bill”.

Abbott demanded an assurance that the opposition would agree to abort the parliamentary inquiry as part of the deal.

With the warrant and the review process, the legislation will contain protections which don’t exist now, when journalists’ metadata can be obtained without a judicial application.

On the other hand, critics point out the police or security agency would only have to establish they were investigating an alleged crime – the leak of official information to a journalist – and they would get the warrant.

It’s unclear how much trouble from media organisations the government will still face over the issue of journalists’ metadata. Labor has said the government should consult them before a final point is reached. Late on Tuesday this hadn’t happened.

Gail Hambly, Fairfax Media’s company secretary and general counsel, told The Conversation a warrant is “very much second choice”.

“We want a judicial warrant obtained before a judge instructed in the legislation to take into account the need of journalists to protect their sources. A journalist should be entitled to notification if a warrant is being sought. And there needs to be an appeal process,” Hambly said.

If the media companies react strongly against the amendment, this might put pressure back on Shorten, although he will be anxious to avoid that.

Independent senator Nick Xenophon is pressing the need for tougher protections for journalists, with amendments that would give organisations the right of reply when warrants were sought. But when the government and Labor are in agreement, Senate crossbenchers suddenly lose the great power they so often have.