Prime Minister Anthony Albanese did the right thing in dashing off to Alice Springs this week in response to the publicity about that city’s crime crisis. But in doing so, he set up a test for himself.

That test will be early, and tough. The first round will come next week, when Albanese and Northern Territory Chief Minister Natasha Fyles receive a report on whether alcohol bans should be reimposed on Indigenous communities.

It’s clear the PM believes they should be. He has canvassed an “opt-out” system to replace the present arrangement, under which communities have to opt in to stay dry. The NT government installed the “opt in” arrangement to replace the bans which lapsed when federal legislation expired last year.

The territory government argued the bans were racially discriminatory, although Fyles has now (sounding reluctant) agreed to an “opt-out” scheme being on the table.

Does the “racism” argument justify what has been the NT’s policy? Undoubtedly imposing bans on Indigenous communities is racially discriminatory, curbing the rights of the Aboriginal people who live there. But the bans also promote “rights” – notably, the right of women and children to a safe environment.

Those who reject bans simply on the grounds of discrimination must be willing to accept some moral responsibility for the harm to the vulnerable that binge drinking is doing.

Albanese still has a way to go to get everyone to agree to the opt-out program. Community consultations are underway, and there’ll likely be mixed views. And he has to keep the NT government on the same page.

Presuming he can announce the opt-out approach, the federal government also needs, within a reasonable time and in conjunction with the NT government, to come up with a comprehensive program for tackling the extreme disadvantage in NT communities in general and the town camps around Alice Springs in particular.

As those on the ground point out, the Alice Springs crisis goes way beyond the alcohol issues, and is endemic. The evidence indicates it is also beyond the capacity of the NT government to cope with it.

The challenges in Alice Springs shot to national prominence just as the debate about the Voice referendum is becoming more difficult for Albanese.

Polling indicates people haven’t got their heads around what’s being asked (indeed, they are unlikely to engage until much closer to the vote). Critics are attacking from the right and the left, including Indigenous Greens Senator Lidia Thorpe.

A range of factors will influence those who are uncertain: the force of the arguments put forth by the government and other advocates, where the Liberals land on the Voice, fear-mongering from “no” campaigners.

Opposition leader Peter Dutton and his spokesman for Indigenous Australians, Julian Leeser, this week again insisted Albanese must put out more detail. Leeser said people he’d have expected to support the referendum were cautious. “They’re saying to me things like, ‘Look I want to vote yes, but I’m just not sure I can because no one can explain to me how this will work.’”

Read more: What do we know about the Voice to Parliament design, and what do we still need to know?

Albanese had hoped keeping the emphasis on the principles of the Voice – pointing out the detail was for parliament – would maximise the referendum’s chances.

But many voters who are uncertain won’t be satisfied without a more precise model. Referring people to the extensive Indigenous Voice report for these details doesn’t wash, especially as the government hasn’t said precisely which parts of that report it accepts.

The public needs the Voice’s skeleton – which may amount just to the government gathering and clarifying what’s out there and putting it into a succinct, clear presentation that also covers off on contentious matters. “Detail” doesn’t mean endless fine print.

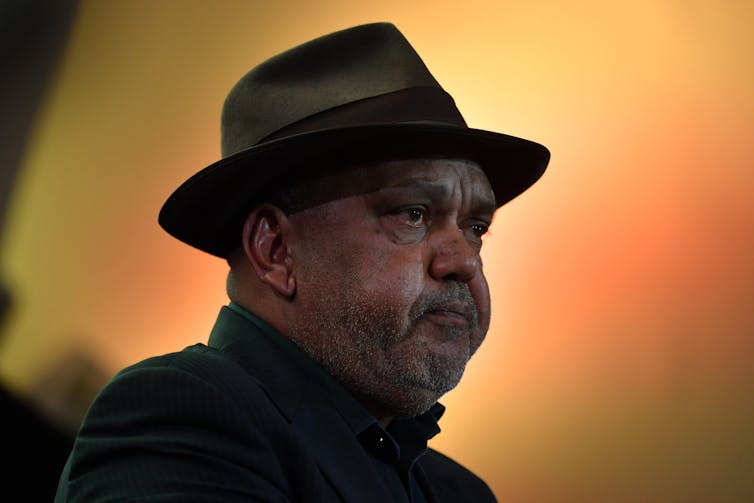

If the government does this, the onus will be on Dutton. It will test whether his questioning is genuine and reasonable, or (as First Nations leader Noel Pearson fears) he is just playing a “spoiling game” – laying the ground for declaring the Liberals will oppose the referendum, as the Nationals have already done.

The issue is complicated for Dutton, whose party will never be united on this. He will be open to damaging criticism if the quest for detail is confirmed as spurious.

Albanese, pushing for bipartisanship, is going out of his way to get Dutton on board (or to wedge him, depending how you see it). This week, he invited Dutton to attend a meeting of the referendum working group, which is advising the government, so he can glean more information. Dutton has accepted.

The Liberals being naysayers would play badly in “teal” seats, at least some of which Dutton needs to win back to secure government. If the referendum went down, Dutton would be loaded with a large share of blame.

Pearson, an Indigenous figure much praised by Liberal leaders at various times, wrote this week: “By playing a spoiling game, the federal opposition will be responsible for destroying the three-decade quest for reconciliation”.

There has been speculation the Liberals might not take a formal position; this would be expedient for Dutton but a failure of leadership.

As the referendum debate intensifies, the stakes rise. Pearson says, “I cannot see how reconciliation will be a viable concept in Australia if the referendum fails”. The fallout from a loss would be huge.

On the flip side, the proponents of the Voice are wrong to raise unrealistic expectations for the body, even if their motives are understandable.

If it comes into being, the Voice will be symbolically important and, if it works effectively, it will institutionalise a compelling and authoritative source of first-hand advice.

Read more: An Indigenous Voice to Parliament will not give 'special rights' or create a veto

But it won’t have all the “answers”, for obvious reasons. Views among Indigenous people are not unanimous. Why would we expect them to be? They are not even unanimous about the Voice. Those serving on the Voice would argue among themselves, as do members of any other democratic, representative body.

More fundamentally, the complex issues bedevilling Aboriginal affairs are “wicked problems”, too often intractable even when governments seek and listen to Indigenous advice.

Those who over-hype what the Voice could do are paving the way for later disillusionment about the body and its role. It is important to be realistic.

Tom Calma, co-author of the 2021 Indigenous Voice report, described its potential value in his Wednesday speech accepting the award of 2023 Senior Australian of the Year. “We must have enduring partnerships, so Indigenous communities can help inform policy and legal decisions that impact their lives and we can recognise the special place of Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander peoples in Australia’s history.”