The last few weeks have seen an extraordinary cross party agreement that environmental regulation of development needs reform. The Prime Minister wants coordination with the states streamlined; the Leader of the Opposition wants it devolved altogether. While the Greens naturally maintain that all existing environmental controls be defended, is there substance underpinning the vehemence of business dislike for the environmental approval process? And what will be the consequences for the environment of any new process?

First it needs to be understood that Commonwealth interests, while substantial, are a relatively narrow subset of the hundreds of issues with which the states have to deal. The Matters of National Environmental Significance governed by the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act only include Commonwealth seas, threatened or migratory species, world and national heritage sites (of which the Great Barrier Reef gets special mention), important wetlands and nuclear issues.

Secondly the Commonwealth and the states already have in place systems that allow the States to undertake environmental assessments as a single process, taking account of Commonwealth interests.

The green tape debate therefore arises about the relatively small number of projects referred to the Commonwealth for consideration (most projects are too small to come under Commonwealth scrutiny) and where the Commonwealth insists on a separate Environmental Impact Assessment for the matters over which they have constitutional powers. Often in such cases the Commonwealth has tended to be more risk averse than the states, leading to tensions and extended negotiations.

Both sides have a case. Conservative state governments in particular are trying hard to rush through approvals for mining developments, even if the approvals come with hurriedly applied conditions in order to comply with state legislation.

The risk of misjudging environmental risk is greatest for the largest and more complex developments. In these cases approval comes not from the environment departments, where there is usually some level of expertise, but from more powerful departments for whom rapid economic development has high priority. Public servants in these departments rarely have the background, or the interest, to understand such issues as landscape continuity or threatened species population dynamics.

On the other hand the Commonwealth has sometimes used its powers clumsily. Commonwealth public servants can be excessively cautious about risk to the assets protected under the EPBC Act. Sometimes conditions appear to be imposed simply because they can be, not because they will reduce risk to the environment. For companies such conditions are but a pin prick in their profits, but pin pricks irritate, especially when the conditions imposed both delay a project and achieve little.

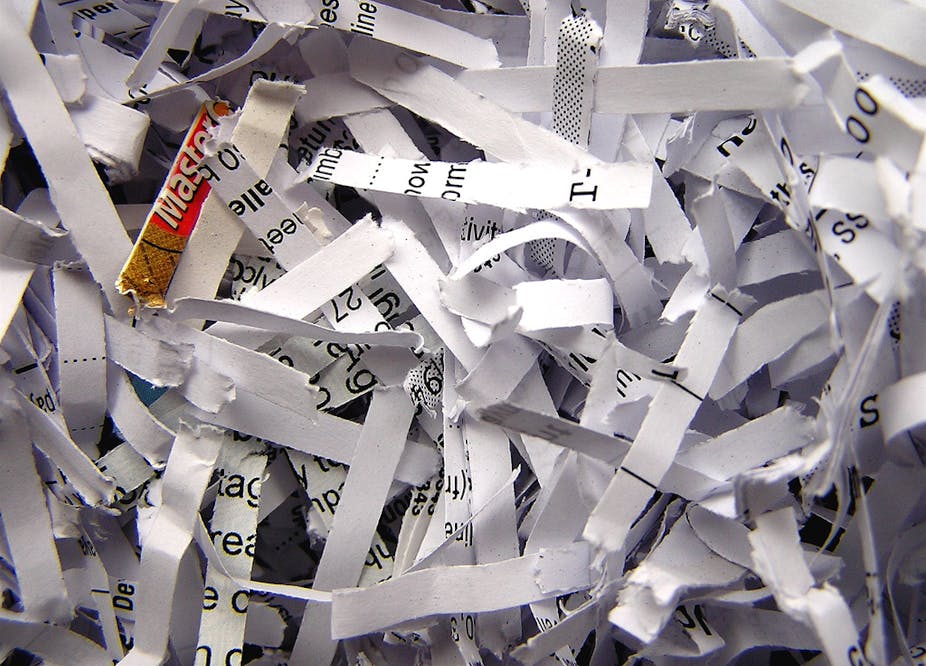

The Commonwealth’s reliance on the cumbersome and bureaucratic environmental impact statement (EIS) process doesn’t help either side with effective or efficient risk management. A recent EIS sent for public review was nearly a metre thick. Not surprisingly the public rarely provide effective input to such documents.

As it is, when conditions are imposed by an EIS they often aren’t audited. If audited, monitoring to determine whether they have achieved their desired effects is rare, and more rarely made public or tested through independent peer review. And almost never does the result of monitoring get fed back into revised environmental practice.

Sadly, given the optimism when obligatory EIS became standard practice, much of the result appears to be tax-deductible greenwash, as well as being the type of green tape now suffering from political backlash.

So what might happen if Abbott’s green tape proposals are implemented? Conceivably the results could be more realistic, and deliver tangible local benefits, given that Commonwealth public servants are often ignorant of local context. On balance, however, the results are likely to be worse for the environment unless there is more fundamental reform.

The pressure to approve developments will increase as the scale at which decisions are being made gets smaller, so local councils and the smaller states and territories will find it very difficult to control large proposals. The skill levels of those involved in environmental decision making are patchy: poor performers will need oversight. And, environment departments are almost always low in the departmental pecking order. They may struggle to have their conditions imposed unless, as now, there is external insistence on compliance from the Commonwealth.

However the focus on green tape could be a blessing. Managed well, the proposed reforms could actually improve environmental management. For instance the Commonwealth EPBC Act powers could be codified so decisions are not subject to the whims of individual public servants (or Ministers) imposing their own levels of risk aversion. The EIS system could be reviewed and the good elements distilled into something both useful, respected and genuinely accessible to the public. In a reformed system, there could be greater investment in expert review of risk, rather than placing the full burden on harried public servants who are forever torn between compliance with legislation and responding to their elected masters.