Well over 5,300 people have been infected and over 2,600 have died in the current Ebola outbreak in West Africa. But these numbers are thought to be gross underestimates as even the most conservative projections now suggest a tenfold increase in deaths before we can hope to contain the outbreak.

The international community has been slow to react to this unfolding humanitarian crisis, but in the past week new commitments have come from a variety of countries and institutions.

So where is Australia in all this? Given the country is home to some of the world’s best-trained health-care workers and medical scientists, you might expect it to be sending teams of highly qualified people to help.

Not helping, blocking

The most notable assistance for the affected West African nations will arrive in the form of 3,000 US military personnel. They will help train health-care workers and build 17 new 100-bed patient care facilities.

The United Kingdom has announced that it too is sending military personnel to the region to assist. The Chinese government has sent a mobile laboratory for testing for the virus and a 59-person team of epidemiologists, clinicians and nurses. Cuba has sent 165 health professionals.

Late last week, the United Nations established a new mission for Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER), and the United Nations Security Council passed a resolution (2177) declaring Ebola “a threat to international peace and security”.

This development alone, which is only the second time in the history of the UN Security Council that it has declared a health issue a security threat, speaks to the gravity of the outbreak.

Back on our shores, some 12 Australian doctors have already travelled overseas with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) to help care for the sick and dying. But they have done so independently and without any support from the Australian government.

In fact, to date the government’s response has been disappointing to say the least.

Last week, the prime minister announced he was offering A$2.5 million to MSF, which has been providing frontline care to those infected. This was the response of the non-governmental organisation:

Médecins Sans Frontières cannot accept any donation of funds from the Australian government. We have been asking countries, including Australia, to evaluate their emergency medical and logistics capacity and make a contribution beyond financial support for over two weeks now and we continue to urge them to do so.

Another A$2.5 million has been allocated to the World Health Organisation to help upscale its efforts. A further A$2 million will be provided to the UK government to support its frontline activities in Sierra Leone.

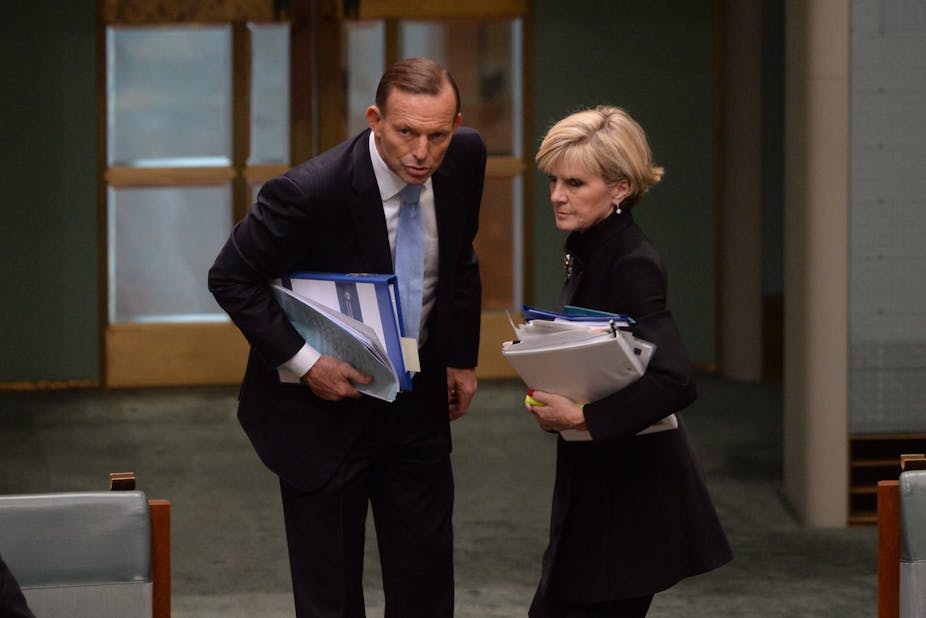

Beyond this, the government has not only ignored calls from the Australian Medical Association to assist countries affected by Ebola by sending medical experts. Foreign Minister Julie Bishop announced last week that any Australians travelling to West Africa must ensure their employers can extract them if they become ill as the government “did not have the capacity to evacuate them”.

Ebola is a priority too

Australia’s actions stand in clear contrast to the activities and measures offered by other countries, such as the US, the UK, China and Cuba. They also stand in stark contrast to the measures the government has proposed to combat the terror sect calling itself Islamic State (formerly ISIL or ISIS) in northern Iraq. These measures so far include an indeterminate commitment of over A$500 million per year and 600 troops.

No rational individual can doubt that IS must be eliminated and that it will take considerable resources to do so. The Australian military is also ill-equipped to offer the type of assistance made available by the US and UK forces. Our military hasn’t been trained to do this type of work and we don’t have anywhere near enough military medical doctors and nurses to send overseas.

Even so, Ebola poses a serious global threat and civilian health-care professionals are ready to be deployed. But the government’s refusal to guarantee it will help any Australian citizens come home if they get sick leaves the decision of whether people can go help to individual employers – and their insurance brokers.

MSF has been overwhelmed by the need in West Africa; it is turning away patients because it simply doesn’t have the personnel or facilities to care for them. In the last few days, local health-care workers in some areas have been murdered over fears they may be spreading the virus.

Money will undoubtedly be needed to help those governments affected by Ebola recover economically once this disaster is over. Until then, what is needed – and needed desperately, urgently – is people on the ground to help contain the outbreak. This means sending multidisciplinary teams of scientific, medical and humanitarian experts, supported by security personnel, to help as soon as possible.

If left unchecked, Ebola poses just as big a threat to Australia’s national interests as Islamic extremists – both are conceivably just a plane ride away.