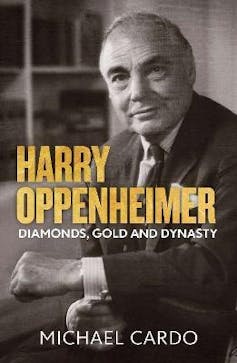

In Harry Oppenheimer: Diamonds, Gold and Dynasty, his outstanding biography of the South African mining magnate who died in 2000, Michael Cardo shows that there is still mileage to be made in the study of dead white males who played a role in the making of South Africa. Based on a remarkable depth of research, it is written in an elegant style which makes for a delightfully easy read.

It is rendered the more impressive by the author’s deep conversance with the debates over the relationships between mining capital, Afrikaner nationalism and apartheid. Cardo is an opposition MP.

Cardo’s reckoning is that Oppenheimer transcended his country’s parochial political arena to become a significant figure on the world stage. As chairman of both Anglo-American Corporation and De Beers Consolidated Mines, he expanded their global reach and dominion.

In South Africa, the Anglo powerhouse came to dominate the economy, which by the 1980s accounted for 25% of South Africa’s GDP and an estimated 60% (or more) of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange.

Meanwhile, for all the limitations of his liberalism – and there were many – Oppenheimer made a vital contribution to political and economic progress in a country hamstrung by rival racial nationalisms. (pp.442-43)

Three dimensions of this biography stand out. First, it paints a fascinating picture of Oppenheimer as a person. Second, it offers a careful assessment of his liberalism. Third, it profiles his behind-the-scenes influence as a magnate.

The man behind the money

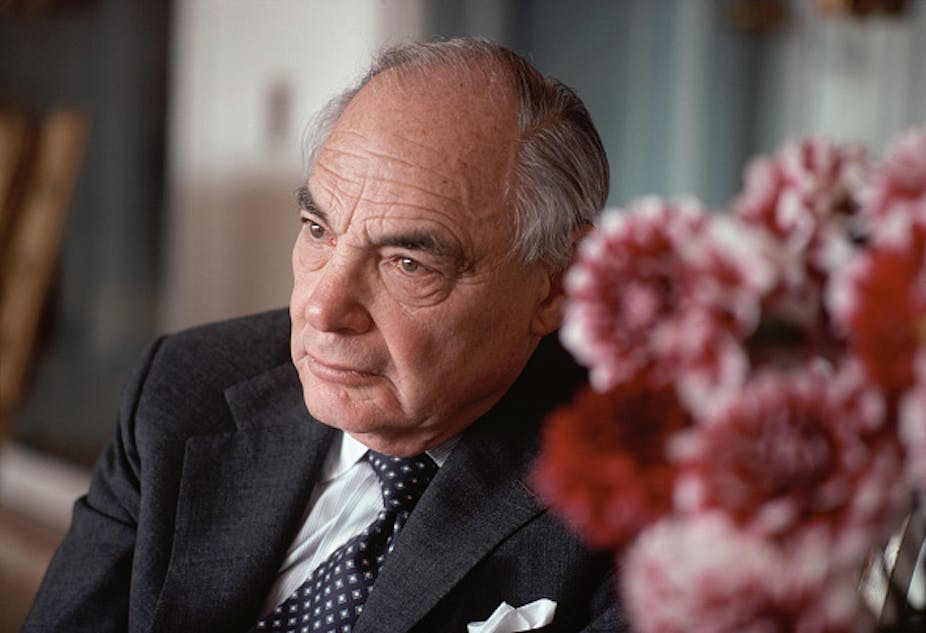

The Oppenheimer empire was built on cheap black labour. Yet Oppenheimer emerges from this study not as a “malevolent monster” (p.1) but as a personally likeable individual, intensely loyal to his friends. One who was highly cultured and sophisticated, with a deep love of art, literature, old books and antiques for their own sake, rather than for opulent display.

His devotion to his Anglican faith was deep and real, underlying his perhaps too-convenient conviction that wealth and power could be combined with “doing good”. He was also highly able. His father, Ernest, was the founder of the Oppenheimer empire, but Harry would become its consolidator (p.18).

By the time of Ernest’s death and his succession by Harry as chairman of both companies in 1957, Anglo had become the world’s largest producer of gold while its twin, De Beers, commanded 90% of the world’s diamond trade.

Born in 1908, Harry enjoyed an exceptionally close relationship with his father, who had converted to the Anglican faith in the mid-1930s. Harry followed in his wake, his Anglo-centricity shaped by his education at public school (Charterhouse) in England before “going up” to Oxford in 1927.

After returning to South Africa in 1931, Harry began his long apprenticeship to his father. After settling at Brenthurst, the “English country house” built by Ernest in Johannesburg, he lived a “blend of business, politics and pleasure”. Then, after a brief (but brave) period in the army, his status as heir to Ernest resulted in his early return to civilian life in 1943.

Oppenheimer now plunged into business, developing Anglo’s interests in the Orange Free State goldfields. By now married with two children, he watched his father meld business with politics. Much impressed by the liberal philosophy of citizenship promoted among troops during the second world war, he sensed the urgent need for social reform. However, while supporting the recommendations of prime minister Jan Smuts’ Fagan Commission that black urbanisation must accompany industrialisation, he clung to a belief in political segregation. His liberalism allowed for more humane treatment of black people while denying them equal rights (p.116).

The conservative liberal

Oppenheimer served as a United Party (UP) MP from its defeat in 1948 by the National Party, which went on to formalise apartheid, until 1957. He left parliament to become chairman of Anglo after his father’s death. He served as the party’s financial spokesman and was touted as a future leader.

Later, when liberals formed the Progressive Party, he lent them his firm support. He became the party’s main funder and power behind the throne.

Cardo characterises Oppenheimer’s liberalism as “pragmatic”, opposing the idea of a universal franchise. Instead, he favoured a common roll qualified franchise. On this basis, he met Albert Luthuli, leader of the African National Congress (ANC), to see if he would play ball (which he wouldn’t). Nonetheless, he gave discreet financial backing to the defendants in the Treason Trial which, beginning in 1956, saw 156 anti-apartheid activists, including Nelson Mandela, accused of treason. Thereafter, he backed proposals for constitutional reform which would steer a middle path between the ruling National Party’s racial exclusivism and the ANC-led Congress liberation movement’s demand for universal franchise.

Regarding himself heir to British colonialist and businessman Cecil Rhodes, he deplored the threat to civilisation represented by “primitive tribesmen”. Yet he had to accommodate Africa’s new heads of state if his ever-expanding commercial empire was to flourish. He struck up cordial relationships with both presidents Kenneth Kaunda (of today’s Zambia) and Julius Nyerere (of today’s Tanzania), despite questioning their socialist policies. Indeed, his fondness for Kaunda survived the latter’s (catastrophic) nationalisation of Anglo’s operations in Zambia in 1974.

Shocked by the Soweto uprising in 1976 and fearing bloody revolution and the installation of a Marxist government, he collaborated with fellow tycoon and philanthropist Anton Rupert to establish the Urban Foundation. Its goal was to improve the conditions of black urban dwellers and promote a property-owning black middle class, thereby laying the ground for an orderly political transition.

Oppenheimer supported a qualified franchise until 1978, but Soweto had changed the game. He now gave his wary support to the Progressive Party’s proposals for constitutional negotiations. These were underpinned by the principles of a universal franchise, federal government, a bill of rights, executive power-sharing between majority and minority parties, minority vetos, and a constitutional court as the final arbiter of disputes.

The influential magnate

Even after his retirement in 1982, Oppenheimer’s influence did not wane. His views remained highly sought after, especially internationally. He exercised all the soft power at his disposal, through Anglo and his personal contacts with politicians locally and internationally.

His advice to prime minister and president PW Botha to inaugurate multiracial negotiations was ignored. But when Botha’s notorious “Rubicon” speech in August 1985 prompted a massive outflow of capital, he urged US companies to resist the disinvestment drive. Meanwhile, he backed initiatives for democracy which would not crash the economy.

All these efforts were capped by Gavin Relly, who had succeeded Oppenheimer as chairman of Anglo, meeting with the ANC in exile. Oppenheimer considered Relly’s initiative “unwise” (p. 375), yet he did not move to stop it. When the meeting was held at Kaunda’s safari ranch in Zambia, it was a roaring success. There was a friendly but robust exchange of views between the old white corporate elite and the new black political elite about the inevitability of liberal democratic governance (p.376). Even so, he confided in UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher that the ANC’s economic strategies were unrealistic and reinforced her own view that support for the ANC was exaggerated and that Mangosuthu Buthelezi, leader of the Zulu-ethnic Inkatha movement, was the dominant black political leader in South Africa (p.377).

Oppenheimer and Anglo now reached out to leading figures in the ANC to reshape their ideas on the economy. In Nelson Mandela they found a man who was willing to listen. Soon he became a regular dinner guest at Brenthurst. Yet, famously, it was not Oppenheimer and Anglo who shifted Mandela’s views on nationalisation, but the advice of Chinese and Vietnamese socialist leaders at the meeting of the World Economic Forum at Davos in February 1992. Oppenheimer grew in confidence as his intimacy with Mandela developed, and the message that private enterprise was essential was getting home. He foresaw a new government with which business could work (p.399). Nonetheless, he had long since sent much of his money abroad! (p.401).

Cardo discounts leftist suspicions of a bargain between powerful white capitalists and the black political elite. He argues that the formers’ influence was marginal and that the repositioning of the ANC’s approach to economic affairs was primarily a result of the collapse of communism and other global pressures. At most, he argues, the ANC’s retreat from its Reconstruction and Development Policy – a redistributive economic framework – and its transition to the conservative Growth, Employment and Redistribution macroeconomic policy was “accelerated” by Anglo (p.413). Yet he does allow that the white business establishment felt an “understandable compulsion” to demonstrate their bona fides to the new government.

Their solution, pioneered by Anglo and Sanlam, the historically Afrikaans insurance company, involved the transfer of unbundled assets to ANC luminaries. They established the model later codified as Black Economic Empowerment (p.413). Ultimately, Cardo concludes, this gave rise to an undesirable form of “comprador capitalism” – the alliance between big business and dependent political elites– for which Anglo and Oppenheimer must share the blame. But he also asks: what else could they reasonably have been expected to do?

This book does not offer a radical re-interpretation of either the Oppenheimers or the Anglo-American empire. But what it does do is to valuably complicate both our understanding of “white monopoly capital” and its relationship to liberalism in South Africa.