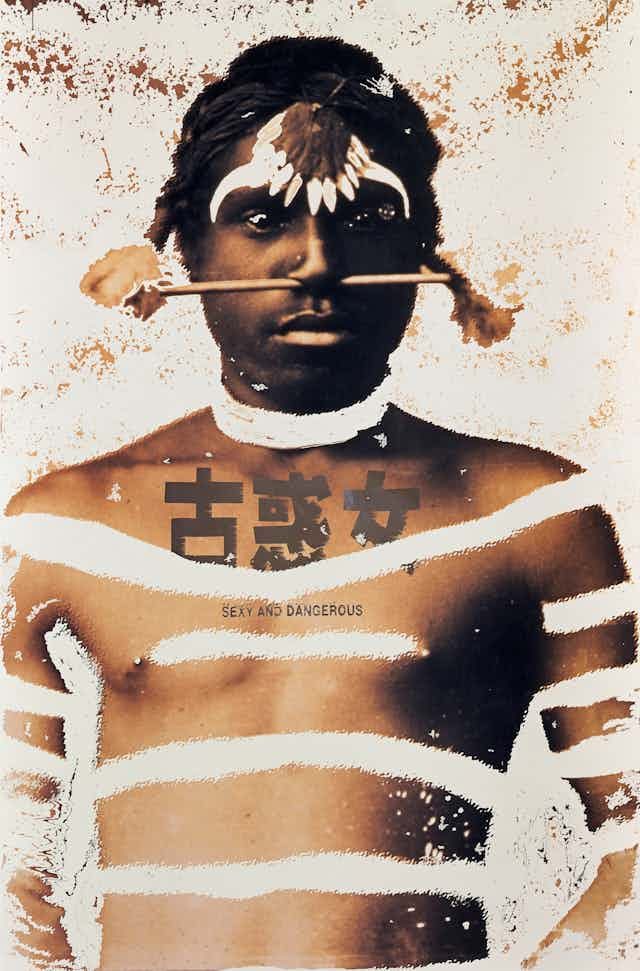

The young warrior looks out at us, his gaze averted. Dressed in his elegant headgear, a rod through his nose and his hair braided, he is photographed naked to the waist. His body decorations in bold white, suggestive of war paint – including one ominously encircling his neck – delineate his strong torso and arms. On his chest are two tattooed inscriptions. One in English reads “Sexy and dangerous,” the other in Mandarin loosely translates as “female cunning” or “shifty femininity” or “mischievous girl.” Who is he?

Brook Andrew appropriated this image of an unnamed “Aboriginal Chief,” a Djabugay man from North Queensland, from the archive of photographs made by Kerry & Co. in the first decade of the 20th century. The Kerry & Co. studio produced images of Aboriginal men and women, often posed in tableaux in front of a painted backdrop and with props of branches and undergrowth to situate them in the landscape.

These photographs on glass plate negatives were reproduced as Cartes de visite (photographs glued onto visiting cards, the forerunner of postcards) to document the “exotic” inhabitants of Australia for the tourist trade. Sometimes named, though in this case only identified as a person of authority, he is dislocated from any sense of locale by judicious cropping of the studio tableau in the background.

Comparing Andrew’s Sexy and dangerous with the original Kerry & Co. photograph there are obvious variances.

Firstly, the rendering in colour of the sepia original brings this man to life, and the enhanced scale to larger than life size underscores his physical presence. He is depicted as a powerful man whose authority is evident in his demeanour, rather than suggested by the anonymous cipher, “Aboriginal Chief.”

The reworked image is designed to hang from the ceiling so as viewers we must confront this man individually, rather than control him in the palm of our hand. We walk around him in the space he occupies in the gallery, he is alongside us, and we are encouraged to engage meaningfully with him.

However, Andrew subverts our encounter by over-painting his body markings, beaded necklet, and armbands so that they seem to slice through the image, segmenting his torso and severing his head. This aggressive rendering of his body echoes a history of brutality inflicted upon Aboriginal people in this country.

The body painting as recorded in the Kerry & Co. version would have likely acted as a means of communicating status or belonging, but in Andrew’s work, it is used to rupture his image. The physical fracturing further reinforces this man’s displacement from country, which is removed in both versions but more obviously erased in Andrew’s painted-out surround. In Andrew’s rendering of the image, this anxious warrior occupies no clearly defined place and the detached sections of his body merely hover in space.

Most intriguing though is the addition of the two texts: “sexy and dangerous” and “female cunning”. Through this overlay, Andrew fuses together the multiple readings he has already chronicled visually with additional inferences about sexuality and otherness.

In the smaller font English text, the sitter’s humanity is established forcefully as erotically charged but also threatening. We see him through the lens of our humanity. He is much more powerful and hence potentially more to be feared than in the Kerry & Co. original. He is the epitome of “rough trade,” who simultaneously evokes dread and desire.

The second and larger font text in Mandarin further complicates our reading of an image that has already engrossed us completely. Its suggestion of queer sexuality may reinforce the notion of rough trade, or it may be that Andrew is reminding us that Australia is now a part of Asia as much as it is a far-flung colony of Britain.

Andrew created Sexy and dangerous around the time of the confrontation in Tiananmen Square, and hence it can be read as underscoring the need for resistance in the face of oppression. Is Andrew urging us to readjust our understanding of what it means to occupy a country whose sovereignty is made manifest in this image of the Aboriginal Chief?

So who is he, this young man photographed over 100 years ago? We are told he is an Aboriginal man from North Queensland whose name was not recorded. He is now dead: all that remains is his image, yet through his act of re-presentation, Andrew gives him life.

As with much of the artist’s work, this image is also a conduit for exploring the slippage in identity by examining how we construct ourselves and how we are constructed through the gaze of others. Depicted with the slick production values of global media culture this Djabugay man is once again made visible.

His presence is palpable; he has iconic status in the gallery, in the media, and on our screens. In his ubiquity, he focuses our attention on the crimes of the past, on the failures of the present and urges us to work toward a just and accountable future.

Brook Andrew: The Right to Offend is Sacred is at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia until June 17.