The decision of a committee of the Oklahoma legislature, by a vote of 11-4, to stop funding for Advanced Placement History classes is national news. Whether this committee vote will actually lead the legislature to stop funding advanced placement history classes is yet to be determined.

As a professionally trained historian who has taught at the University of Oklahoma for more than twenty years, I hope that the legislature and the governor do not ultimately take this step.

Those who favor this withdrawal of public funding claim that the AP standards emphasize the “bad” or “negative” aspects of American history, at the expense of the idea that the United States is “exceptional” because it has grown up without the class conflicts and religious strife that divided many parts of Europe for centuries.

I support the AP history standards because, first of all, I have actually read them. A fair reading of the standards released in the Fall of 2014 is the most effective refutation of the indictment that there is a political agenda at work.

To be frank, however, I fear that these opponents of AP history will not be moved by any evidence that a history professor like me would offer them.

What causes us to disagree so strongly is a deep difference over what history actually is and how its mastery should be measured.

Is history a story of how great people became “great”?

Is history the story of how a self-evidently great people came to be “great”? Some people clearly believe this, and they are not all “political extremists.” Any visit to any book store or library will yield a shelf full of books to feed this appetite.

And, if one looks at the textbooks assigned to students at other points in American history —- such as the Cold War -—one will find narratives of triumph and superiority represented as “objectivity.”

Over the last fifty years, social conflict in our society over who belongs here (are you a “real American”?), and whose creativity, labor and struggle have “built this country” (and at what social cost), have exposed an uncomfortable fact of life: we do not agree about how to answer these fundamental questions.

Many of us who were born here or who have chosen to become American citizens have direct experience with being excluded, discriminated against and called “un-American.” The history of the economic and social development of the country is full of examples of often violent struggle over wages, hours, conditions of work, just as in other countries.

History is a living process, not a ‘thing’ to be memorized

The way history is presented today in class rooms across this country, and as it is reflected in the latest AP standards, accepts that these disagreements are, in their very essence, what “history” actually is.

Even after any reasonably free and open society resolves some fundamental questions (the decision to end slavery and legally enforced segregation) for itself, opponents of these decisions do not just become magically convinced by an “idea whose time has finally come.”

The process of disagreement and negotiation continues with we hope, less violence and more mutual understanding than before. In this sense, history never reaches its “destination” or its “end.”

History is a living process that we cannot — and dare not– live without. The AP history standards focus on processes that are initiated by humans as they live together and which continue shape their lives over generations, not on facts about great moments and their visionary authors.

Such moments and such people surely do exist, but theirs is not the whole story. If some “great names” are absent from the AP history standards, it is not because they have been written out of history, but because the AP history standards are a framework within which and through which one makes sense of details.

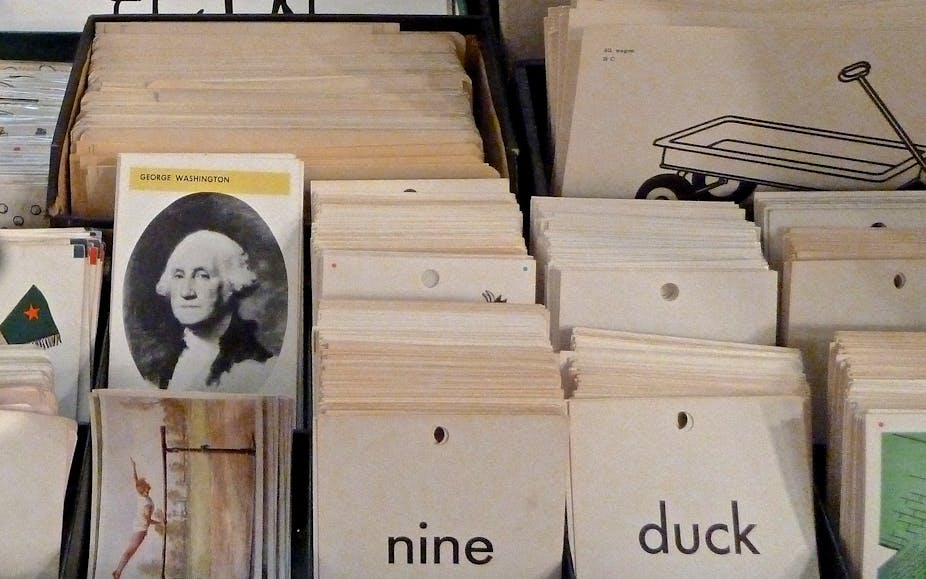

If all you have is a pile of flash card facts — key dates in American history — you really don’t know anything. What you need to know is who assembled these facts and why? You should ask to see the sources and examine the sources of selection.

When you go to the AP history standards you will find a list of all the professors who took part in devising these standards. They come from all kinds of educational institutions — from community colleges to Ivy league schools.

The historians who wrote the history standards understand history as a process, not a “thing” to be memorized. And, once you have assembled the strongest available evidence, you will, as the scientific method requires, come to the same result: human beings are complex and contradictory.

Beyond that, the lesson of history is also like that of the sciences: we must reckon with the diversity of life and form, which has always been humanity’s toughest challenge — and it always will be.

Getting rid of AP history ignores the rigors of this reality rather than meeting its real and enduring obligations upon all of us.