When the federal government asked the Productivity Commission (PC) to conduct a review into certain aspects of workplace laws, it argued a “root and branch” inquiry was urgently needed.

As everyone gears up for yet another round of submission writing, we are expected to ignore all the other times the same questions have been asked and answered. The PC inquiry, and the government’s terms of reference, assume there are problematic gaps in our understanding and knowledge of workplace law. But this stance requires us to act like the mythical goldfish with its three-minute memory span and jettison the monumental efforts of the recent past to deal with these same issues.

Groundhog day

Law reform in the area of industrial relations has been a constant feature of Australian political life since federation, but the drive for change has been particularly intense since the 1990s. Parliament has been called on to consider legislative change to workplace laws at least 47 times between 1997, when the Coalition government’s Workplace Relations Act was passed, and the Rudd government’s Fair Work Bill in 2008. In most cases, an explanatory memorandum was produced, which set out the problem being addressed, the proposed means of addressing it and the likely consequences of adoption.

An examination of the memoranda shows that all the topics slated for review by the PC have been subjected to this process. In addition, parliamentary committees reviewed many major proposals for change. In the most important cases of law reform, massive numbers of submissions were received from stakeholders, experts and other members of the public (the very people now courted by the PC to respond to its review).

Even if we limit our attention to the relevant Senate Committee for workplace laws, there is a plethora of reports on the very matters now said to require urgent review, from “go away” money, to the impact of minimum wages on youth employment. These reports contain a wealth of empirical, theoretical, historical and practical information on the operation of the law and the likely consequences of change. According to the Parliamentary Library register of reports, 31 Senate reports on workplace laws have been produced since 1997.

A large number of other Senate inquiry reports deal with related areas also relevant to the PC review. This includes social security reform, labour market strategies, migrant labour, vocational training, discrimination law and the particular requirements of certain industries including building and construction. So much change has occurred that we now have the benefit of comparative research on the operation of different forms of legal regulation of the same topic.

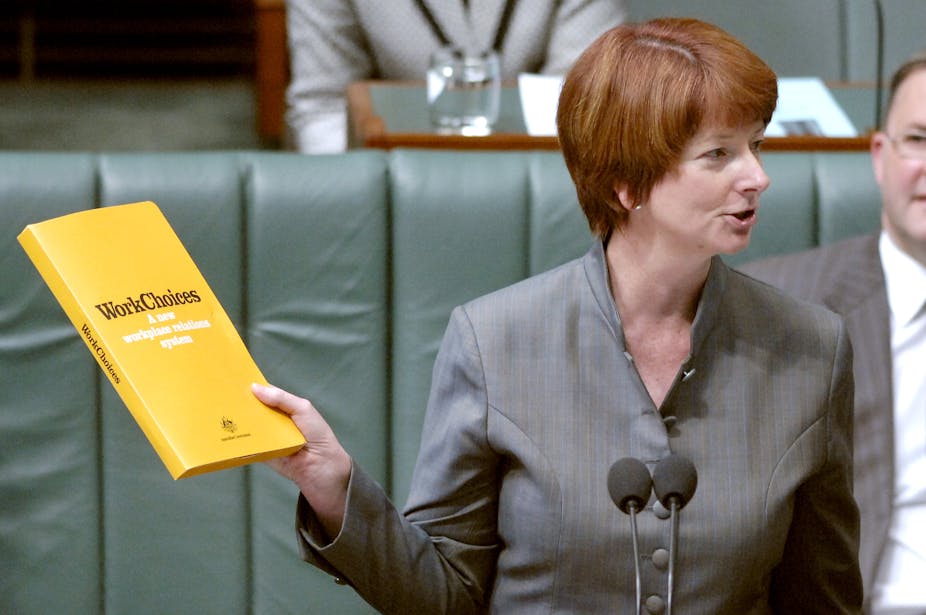

The current Fair Work Act 2009 (FWA) was itself the subject of detailed policy work and consultation and a comprehensive review. The FWA was sold as a root-and-branch change to the WorkChoices framework that preceded it. In fact, the current legislation retains many aspects of the earlier WorkChoices changes, a fact rarely acknowledged in the political debates about the need for reform.

It is not just the parliament that has orchestrated large-scale examinations of the issues that are now claimed to require examination. The IR system itself generates research and review.

For example, an initiative of the Howard government was to create a minimum wage research function to inform the setting of the national award rates of pay. From 2006, the Australian Fair Pay Commission headed by Professor Ian Harper commissioned high-quality research on many aspects of wage fixation in this country. The body now responsible for wage fixing, the Fair Work Commission, continues with this approach. All these reports are available on the commission’s website.

The Fair Work Commission and its precursors have created many of the working condition standards present in awards, agreements and statutory minimum standards in the FWA. The right to request flexible work for family purposes, for example, was the product of several years’ investigation by the commission. Thousands of pages of transcribed evidence and exhibits from this case are still available.

It is hard to imagine any issue relating to work and family not raised during this process. The then Coalition government’s contribution to it was to argue that the matter should be left to market forces. Yet work/family is on the Productivity Commission’s agenda.

The Fair Work Commission is required by law to review the operation of the modern award system, and questions of penalty rates among other PC Inquiry matters have been, or are being, investigated in the context of contemporary economic and social conditions.

In 2012, the Independent Inquiry into Insecure Work presented a report based on extensive evidence. In 2005, the Australian Human Rights Commission produced its report on Men, Women, Work and Family. Public research institutions like the Australian Centre for Industrial Relations Research and Teaching and the Centre for Work + Life and private think tanks like the Institute of Public Affairs have pumped out a stream of quality research dealing with all the issues now before the PC.

So, what is really going on?

With one exception, the agenda presented to the PC by the government is the same Coalition agenda for radical change to workplace laws that we have been studying since the 1990s. The key motivation is lowering unit labour costs, empowering employers and marginalising collective action: that’s no surprise, and no change from the original Howard plans.

The new element in the PC’s issues papers is the vague suggestion that competition law generally should apply to industrial relations. An exemption from the operation of such laws currently applies to unions, basically because without this carve-out, virtually all union action would be unlawful.

Yet even here this matter has been raised and thoroughly reviewed. In 1999 the then National Competition Council was asked to examine the workplace law exemption from competition rules for the then treasurer, Peter Costello. One finding was that without the exemption, it would be impossible for Australia to meets its international obligations to adhere to the ILO Conventions on freedom of association and the right to collectively bargain. Impossible then, impossible now: so why is the question being raised again as if that finding did not exist?

Given the vast truckloads of materials about each of the PC’s agenda items, why is a review needed? What is different in Australia’s society and economy since the last time we looked? Just about everything is known about minimum wages, penalty rates, work and family and unfair dismissal. Virtually all that information is already in the public domain. The strengths, weaknesses, failings and complexities of Australian labour law are well known.

The government’s need is not intellectual but political. The PC inquiry is necessary not because the government doesn’t know all the options and their likely consequences, but because most ordinary people don’t agree with that agenda and it needs a mechanism to soften this opposition. Many people are wary of radical industrial relations reform, and that’s something they’re unlikely to forget.