Pity the poor consumer who wants to make informed decisions about eating cod. Conflicting reports on the state of cod stocks range from misinterpretation of the science – such as the Telegraph’s story that there were only 100 adult cod left in the North Sea (the correct figure was around 21 million) – to misunderstanding over the state of cod stocks in different territorial waters.

The North East Arctic cod stock is currently booming and provides much of the cod consumed in the UK, while the North-west Atlantic cod fishery which collapsed 20 years ago has not yet recovered, and several other cod stocks remain at historically low levels. Fisheries management is complex, and reporting filled with errors and omissions only adds to consumers’ confusion.

Television programme Masterchef stirred up a fuss this week after its website pointed viewers to the Marine Conservation Society’s guidelines for sustainably harvested fish. Scottish trawlermen were reported to be angered by the MCS’s classification of cod from the Irish and North Seas and from the west of Scotland as a “fish to avoid”.

While the MCS does place cod from these waters into its highest danger category, the Scottish Fishermen’s Federation chief executive, Bertie Armstrong, said:

Scottish fishing has tried extremely hard to be sustainable. Our beef about the Marine Conservation Society traffic light list of guidance is that it is superficial and illogical. If anybody buys fish in the United Kingdom then it has been fished within a quota and is entirely sustainable. That’s the measure of it.

In fact the SFF comments referred only to North Sea cod, and not to the Irish or west of Scotland stocks as implied in the Guardian’s reporting. So, cod or no cod? No wonder the fish-eating public is confused.

Science and industry

European fisheries management advice is provided by the International Commission for the Exploration of the Seas (ICES) which bases its assessments on data from commercial fish landings and from research surveys. These data are used to reconstruct trends in historic stock size and fishing mortality and to forecast what the stock will do over the next few years at different levels of harvest.

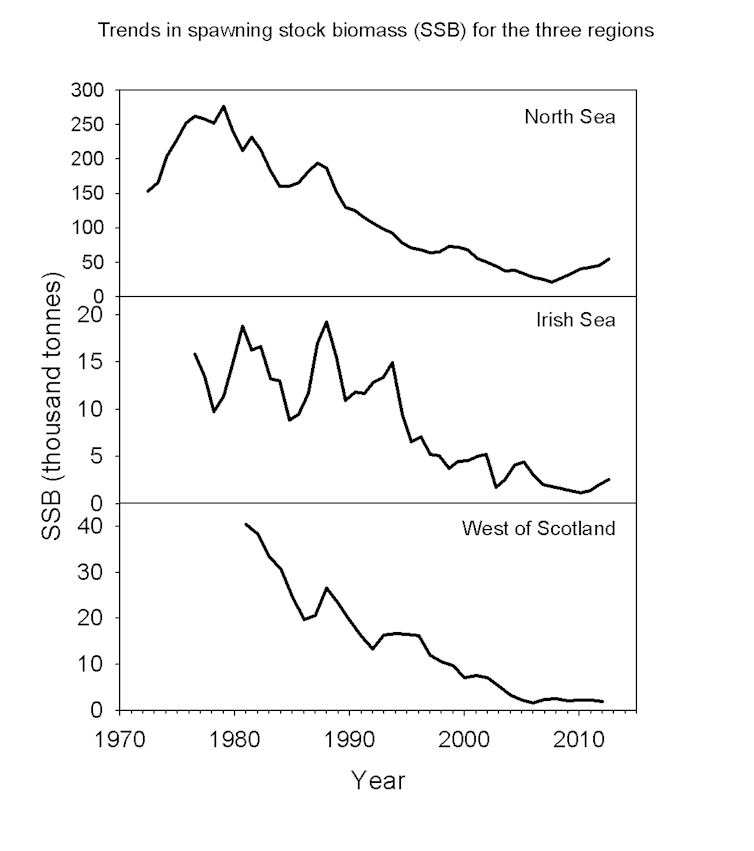

From the huge amount of publicly available reports available from ICES, here are charts showing the trends in cod spawning biomass in the North Sea, Irish Sea and to the west of Scotland.

If the weight of mature fish in a stock (the spawning stock biomass) is reduced to too low a level it will not be able to replace the number of fish removed by fishing and natural predation. However, fish stocks cannot increase indefinitely due to natural ecological limits, an ecosystem’s “carrying capacity”. There is therefore an optimal amount of mature spawning fish which generate the maximum surviving offspring. If harvest rates are adjusted so that the spawning stock biomass is at this value then the fishing is said to be at “maximum sustainable yield”, and achieving this is the aim of current fisheries policy in many countries.

So is North Sea cod being “sustainably harvested” at current levels? It depends what we mean by “sustainable fishing”. However, the widely accepted definition for a stock which has recovered, and so is sustainable in the long-term, is when the level of removals allows the spawning stock biomass to be at the level which will give maximum sustainable yields. According to the ICES estimates, fishing mortality on cod in the North Sea is currently still above this level.

So regardless of a legal quota of cod for fishers to land, fishing mortality is still too high and the cod stock size in the North Sea is not yet at the level which will allow a long-term maximum sustainable yield. However, the quotas being set should allow the North Sea stock to continue to rebuild over time – they are not set so high that overfishing is likely to cause a further decline in the spawning stock biomass.

Livelihoods on the line

It is certainly true that the UK industry has worked hard for many years to try and ensure that cod stocks recover. Many of the measures adopted have involved sacrifices from the industry, including the decommissioning of vessels, introduction of fishing gear modifications to reduce the by-catch of small cod and actions to avoid areas where young cod congregate.

It seems these efforts are beginning to have some effect in the North Sea, as the stock assessment shows the amount of mature adults is now rising. In contrast there has been only limited improvement in the Irish Sea, and none at all in the west of Scotland. Why these stocks are not improving, compared with the North Sea cod, is not clear. Possible reasons include interactions with other fisheries, environmental changes or increased natural predation. There is no clear scientific answer yet although there is evidence of environmental changes such as rising sea temperature and changes to plankton. It has been suggested that these changes could be affecting the survival rates of young cod in particular, but there is no definitive proof.

The steady recovery of cod in the North Sea since 2009 does show that the stocks can respond positively, but does this mean the Marine Conservation Society should change its consumer advice? If one accepts the targets for a recovered stock associated with maximum sustainable yield, then there is clearly still some way to go.

Perhaps we need to describe fishing for cod in the North Sea at present levels as fishing ‘responsibly’, rather than ‘sustainably’. This would both acknowledge the vital role that the industry is playing in re-building the stock but also acknowledge that this stock is not yet at the level we want to see for long-term sustainability.