It’s the race that stops a nation … and is worth a cool A$6.2 million. So what goes into the raceday preparation for the equine stars of the show?

Thoroughbred racehorses have unique anatomy and physiology that suits them well for racing at high speeds. There are very few 3,200m Thoroughbred races in Australia, and the horses that make it to the final 24 in the Melbourne Cup are truly elite equine athletes.

They have superior oxygen transport and an ideal mix of muscle fibre types, and are able to efficiently gallop at high speed. But winning the race also depends on how the horse behaves on the day, and of course, several ounces of good luck.

Built to win

While Phar Lap’s massive heart is an Australian legend (and is on display at the National Museum of Australia), horses racing in the Melbourne Cup will have big hearts with exceptionally high capacity for pumping blood to their muscles.

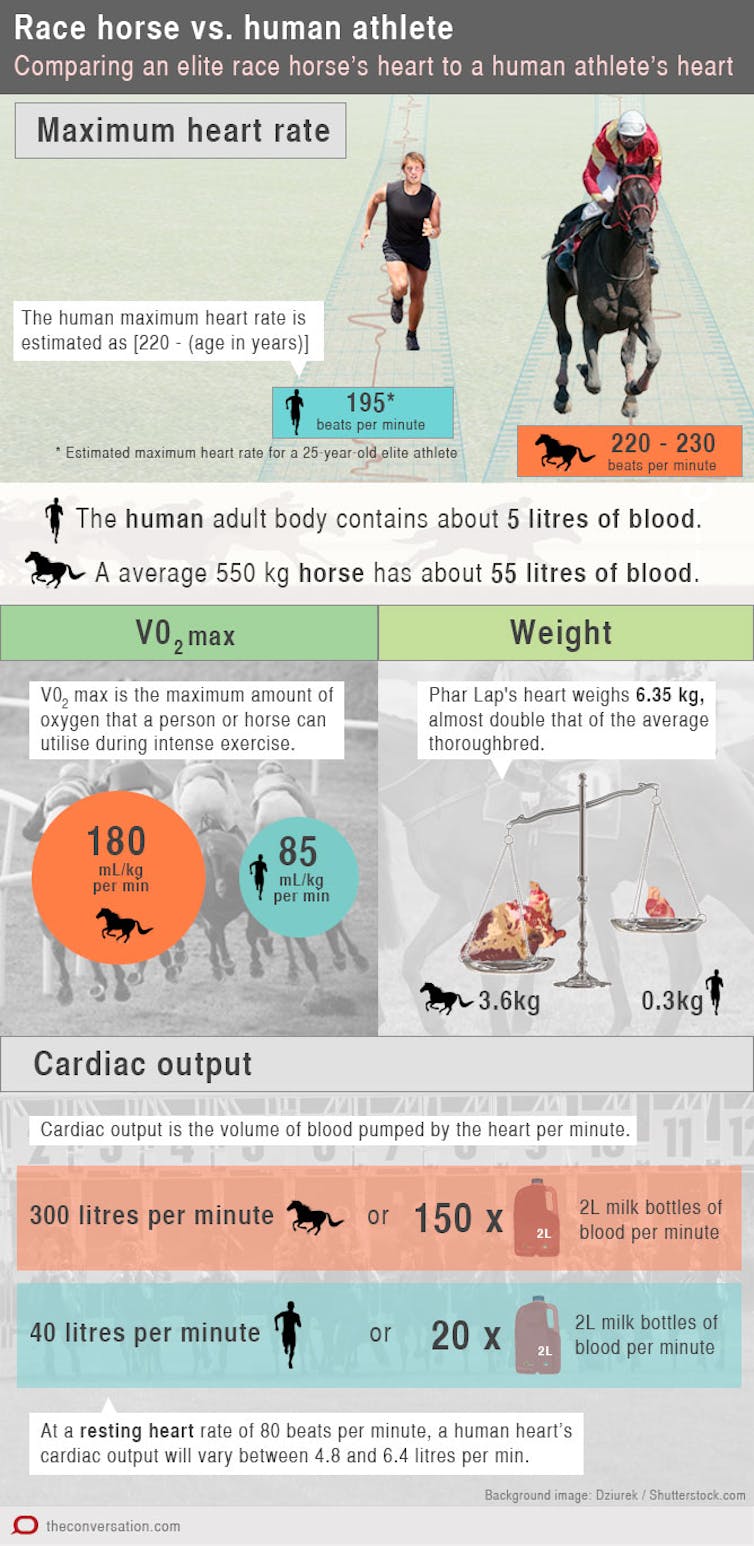

During the race, each horse’s heart rate will hit 220-230 beats per minute, with each beat pumping around 1.3-1.4 litres of blood (this is called stroke volume). To put this in perspective, around 300 litres of blood will be pumped to each horse’s muscles and other tissues during each minute of the Melbourne Cup race.

That blood also has an extraordinarily high concentration of haemoglobin – its oxygen-carrying component – much higher than that of elite human athletes.

These factors combine to enable an elite racehorse to consume approximately 250 litres of oxygen during the race.

On average, horses in the Cup will consume oxygen at maximum rates of around 180ml per minute for each kilogram of body weight after the first minute of the race.

Better race results could be expected in the horses with the highest oxygen-consumption – but a win depends on more than just higher aerobic capacity. At some stage in the race every horse will need to do a short sprint, and must also possess the anatomy and physiology suited to a short burst of speed.

These elite horses will have just the right combination and number of different types of muscle cells to provide the ideal mix of endurance and acceleration.

The best Thoroughbred racehorses have higher proportions of fast twitch oxidative muscle fibres (FOG), which are well suited to fast contractions, oxygen metabolism and fatigue resistance.

In contrast, slow twitch fibres (SO) are better suited to endurance races over 50 kilometres or more.

A higher percentage of fast twitch glyolytic fibres (Type FG) provide for high speed over sprint distances of 400-1,000m.

In comparison with this year’s Melbourne Cup contenders, Black Caviar probably had a higher ratio of muscle mass to body mass, coupled with a higher percentage of Type FG muscle fibres, which provided her the ideal muscle structure and function suited to racing over sprint distances of 1,000-1,200m.

Training for a two-miler

As I said earlier, there are few races in Australia as long as the 3,200m Melbourne Cup, so training for the race needs a mix of slow and fast gallops and short distance sprints of 400-600m.

The trainer has the challenging job of making the right decisions each morning in order to promote fitness, but not overtrain and tire the horse out for a few days at just the wrong time.

While there is no science in these day-to-day decisions, the art of the trainer is still very important in preparing the individual horse to be at peak physical fitness and emotional state on the day.

(Yes, emotional state. More on that in a minute.)

The horse will usually have its final sprint or fast gallop workouts 3-5 days before the race before being maintained with slow exercise each day until the race – much like a human athlete tapers before a marathon.

Daily feed intake is usually decreased on the day of the race – having a big mass of food in the intestines isn’t ideal.

Horses in the Cup may have included treadmill training in their preparation for the race. Use of high-speed treadmills is now much more common in the larger training businesses, and adoption of this technology seems more common in Australia than in other countries. A treadmill is particularly useful for monitoring and maintaining a horse’s heart rate during training (see the video below).

Horses racing for the Cup must also pass an intensive pre-race inspection by experienced veterinarians, who ensure that the welfare of the horse is not compromised.

Horse psychology

Poor behaviour before or during the race can seriously impact a horse’s performance. Horses with over-excitability before the race, usually shown by agitation and excessive sweating, tend to perform less well than their calmer race mates.

I have even seen a horse so agitated before the Melbourne Cup that it had to be withdrawn because it refused to go to the starting gates.

Likewise, horses which do not relax during the running of the race pull hard against the jockey’s trying to restrain the horse. This costs energy, so the horse’s efficiency of galloping is decreased, resulting in poor performance.

Of course, there are other factors to take into account, such as the jockey and handicap.

But from a purely equine perspective, horses in the Melbourne Cup must win the genetic lottery, respond to training and racing programs over several years and be in just the right mental state on the day.