Keeping household surfaces clean is a daily chore for most families, but there may be unseen consequences for children’s health. Overusing cleaning products can increase the risk of childhood obesity, according to new research, as exposure causes changes in the bacteria which live in children’s guts.

The research, published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, compared how much mothers reported using cleaning products with the rate of obesity in 757 children at the age of three. Faecal samples were taken from the infants at three to four-months-old and the researchers investigated associations between microbial changes and being overweight at age three. The researchers found a link between heavy use of cleaning products, microbial changes and children with a higher body mass index (BMI).

However, higher disinfectant usage was also reported among households with infants who received antibiotics around the time of birth; who were exposed to cigarette smoke; or were delivered by caesarean section. The results may therefore reflect several interlinking factors. Obesity was less likely to occur in breastfed children, but breastfeeding was also linked to lower disinfectant usage, which makes it difficult to tease apart these two factors.

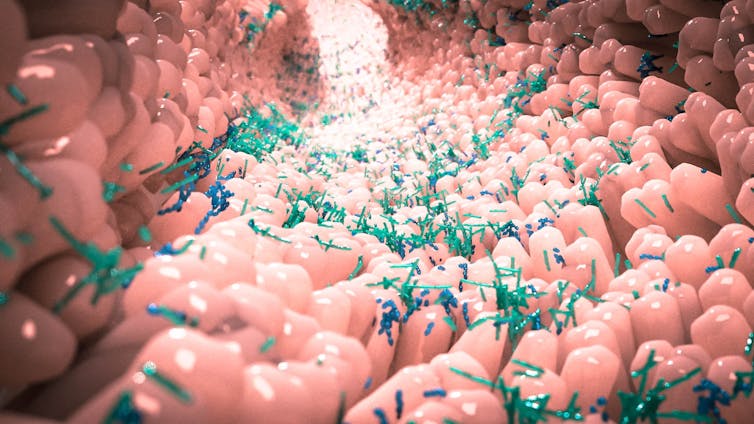

The microflora of the human gut

The prevalence of obesity has seen a dramatic global rise over the last 30 years, leading to increases in related health problems. At the same time, our understanding of the microscopic life we share our living spaces with has grown. Most microorganisms are not harmful and many of them can colonise our digestive system, forming our “microflora”.

We pick up our microflora from our environment, starting from our mothers, and then other household members and even our pets, throughout our lives. Most of our gut microflora are obtained through the mouth, for example during eating, drinking and brushing our teeth. All of our bodily surfaces, including gut, airways and skin, are covered by bacteria. Household cleaning products kill off microorganisms, including the good ones, preventing them from reaching our guts.

We’ve all heard that it’s good for children to “play in the dirt” and there’s a lot of truth in that. Having a diverse microflora is healthy. Dominance or “overgrowth” of one particular group of bacteria can lead to an increased risk of developing many health problems, including obesity, allergies, inflammation and type 2 diabetes.

The more “diverse” the community of bacteria that live in our gut, and the more balanced our diet is to sustain and feed those bacteria, the less chance there is of one type of bacteria associated with a disease being able to flourish.

Gut bacteria and obesity

Obesity has previously been linked to a dominance of one certain type of bacteria, known as Firmicutes, over another called Bacteriodetes, in the intestine. In the current study, Lachnospiraceae (a family of bacteria in the Firmicutes family), were found to be more abundant in infants from households that use cleaning products and in subsequently obese children.

Lachnospiraceae are also more efficient in breaking down food than other species, so that they extract more energy which causes weight gain as the human gut absorbs it. The exact mechanism linking gut microbiota to obesity is not currently well understood, but it is well established that certain bacteria, particularly the Firmicutes, can increase energy production from the diet which can increase the likelihood of obesity developing.

Diseases often emerge from particular groups or even species of bacteria that dominate the rest. This recent research demonstrates that overusing cleaning products may promote this shift in microbial dominance. Childhood obesity may be one of several threats from our attempts to maintain sanitised environment for children, the results of which we’re only beginning to understand.