It has become one of the fastest growing political campaigns in human history, surpassing similar battles against the tobacco industry and the fight against apartheid in South Africa. Its logic is simple: the only way to avoid climate change and dangerous levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is for most fossil fuel reserves to stay in the ground.

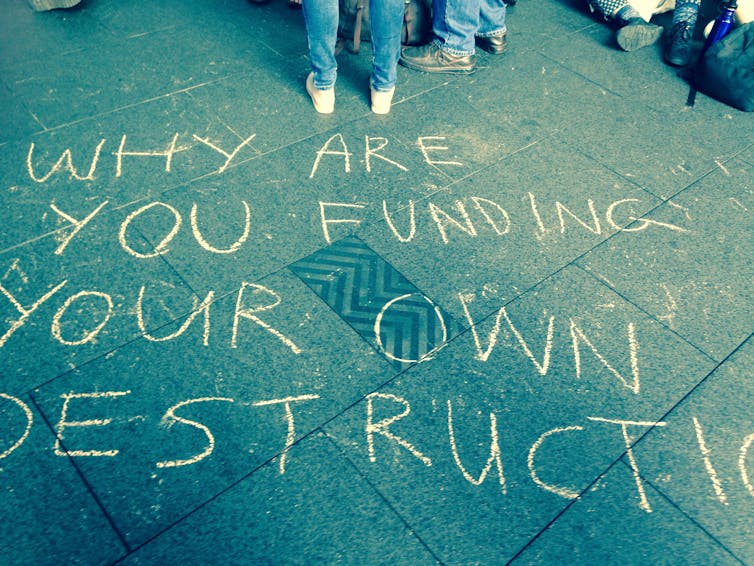

Campaigners launched the fossil fuel divestment campaign in the early 2010s. Their argument was that you curb consumption of fossil fuels if you stop investing in the companies involved in extracting and burning them. Create a significant enough stigma, they argued, and this issue will shoot up the political agenda.

In the past five years or so, investment funds, public institutions and individuals have duly divested around US$6.15 trillion (£4.6 trillion) of fossil fuel assets. It has helped that the campaign attracted a number of prestigious institutions early on, including the British Medical Association, University College London, University of California, the Church of England and the World Council of Churches (representing more than a half billion Christians globally).

The campaign gained further traction after a London-based think tank argued that fossil fuels were in any case a bad investment because the true costs of environmental damage had not been priced in and that at some point there would be a severe correction.

The battle is far from over, however, as demonstrated by the recent decision of the Church of Scotland not to divest. One of the cornerstones of European faith, whose teachings have helped shape everyone from Robert Burns to Rupert Murdoch, its annual general assembly held an impassioned two-hour debate on whether to remove oil and gas stocks from its £443m investment fund.

The high road

The Church of Scotland has form in this regard: it had already divested its coal and tar sands investments two years earlier. Ahead of the latest debate, its official general assembly report summarised the issue as follows:

It is deeply uncomfortable for the Church, as a caring organisation concerned about climate justice, to continue to invest in something which causes the very harm it seeks to alleviate.

While we have profited from oil and gas exploration in the past, we now understand that financing the future exploration and production will take us away from fulfilling the Paris Agreement and delay the transition to a low carbon economy.

Yet the approximately 1,000 commissioners attending the General Assembly Hall on the city’s Mound, next to Edinburgh Castle, narrowly disagreed: 47% in favour and 53% against. Coming from a nation which already gets most of its electricity from renewable sources, and whose government has indicated the end is in sight for fossil fuel vehicles on the roads, it was undeniably a disappointment.

Representatives were persuaded that it was better to stay invested and seek to influence better behaviour than to pull out altogether. Reverend Jenny Adams, who had brought the motion in the first place, argued that all the evidence suggests oil and gas companies have little intention of changing quickly enough to satisfy the Paris agreement. She said:

There is a need for climate emissions to peak by 2020 and if we just keep talking, too much time passes and change is not coming fast enough.

She is surely right about this. There may be traditional wisdom in engaging with fellow shareholders and board members on matters pertaining to large companies, but the church’s decision looks naïve in relation to this sector.

To give just one example, consider that approximately 94% of shareholders of the oil giant Royal Dutch Shell voted last year and again this year to reject emission targets that would comply with the Paris climate accord, as it was deemed “not in the best interest of the company”. How do you persuade a bloc like that to change its mind?

Amen corner

While the Church of Scotland’s decision to sidestep divestment may have been a setback to the movement, there have been recent successes, too. The Church of Ireland committed to divest its fossil fuel assets earlier in May, while an international coalition of Catholic institutions, including the Scottish Catholic International Aid Fund, pledged in April to divest investments totalling £6.6 billion.

Municipal administrations including New York and Paris are also divesting from fossil fuels and shifting their investments towards renewable energy sources – evidence that the global divestment is making an impact on public policy.

This certainly seems prudent, as newly published research suggests that the “carbon bubble” could “burst” in the next two decades as demand for fossil fuel energy falls despite population increases and burgeoning global economic growth.

The study projects that the global fossil energy demand will drop by as much as 40% by 2050. If that comes to fruition, it would mean containing global warming levels to 1.5 °C, which is the aspirational goal of the Paris climate accord.

That would be great news for environmentalists, most especially for those living on the front lines of climate change such as in the Pacific, less so for investors in fossil fuel businesses – Presbyterian or otherwise. It’s a strong signal that this global divestment movement may still be a long way from its peak.