Warning: Some of the links contained in this article direct readers to graphic video footage.

“Violence isn’t new. It’s the cameras that are new.”

This statement appeared in my Facebook news feed the same day that Lavish Reynolds used her mobile phone to record the moments after her boyfriend, Philando Castile, was fatally wounded by a police officer in Falcon Heights, Minnesota.

The live stream appeared on Facebook before being temporarily deleted, allegedly due to a software glitch. But by the time Facebook had restored the video, it had already gone viral.

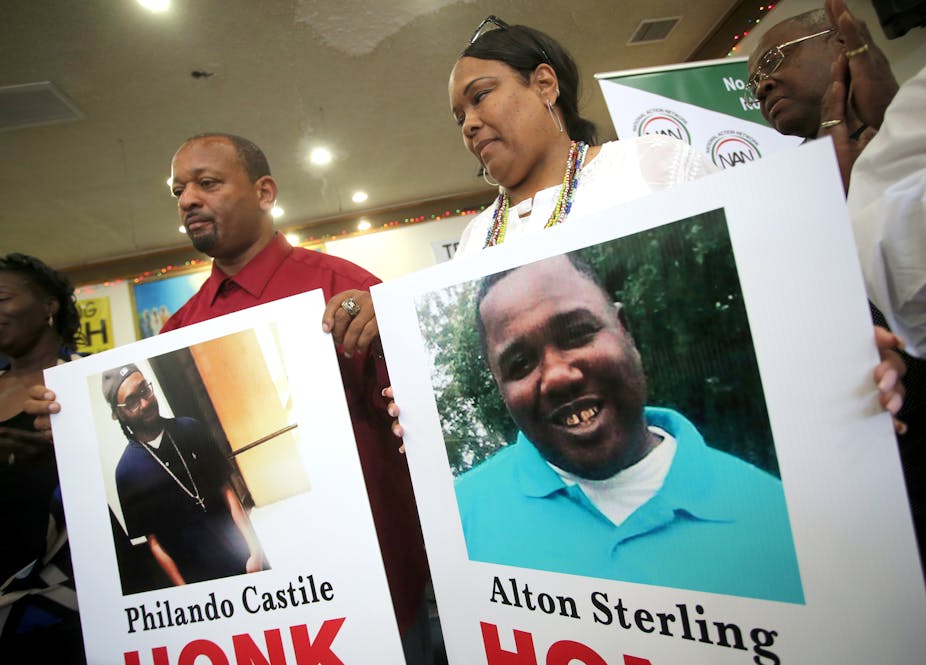

Reynolds’s video bore witness to the shooting of a black man by police officers, not even the only one in the US that week. The day before Philando Castile was killed, videos of two police officers unloading bullets into the prone body of Alton Sterling began circulating online.

These videos are very hard to watch. Doubtless many people have chosen not to watch them, in part because of their graphic content, but also because such viewing can often feel a lot like voyeurism; akin to slowing down and staring out the window as you drive past a gruesome car accident.

But I did watch the video live streamed by Reynolds. And I have watched it several times. I can testify that repeated viewings don’t make it any easier to digest – but I think it is important that we watch.

The video begins shortly after Castile has been shot, and documents Reynolds’s reaction to the altercation with the police officer. She repeatedly explains the facts of the shooting, conversing with the officer, who continues to aim his gun at Castile, and talking to her boyfriend, who lies slumped back in the driver’s seat. Blooms of blood spread across his white t-shirt and we briefly hear him moan, his head slung backwards, before he goes quiet and appears to be unconscious.

The streaming continues as Reynolds is commanded to get out of the car by another officer, is forced to walk backwards away from the vehicle and made to kneel on the sidewalk. She is handcuffed and placed into the back of a police car along with her nine-year-old daughter, who also witnessed the shooting.

All the while, Reynolds recites details of the shooting with a sense of urgency, as if her own life depends on them. This is interspersed with moments when the magnitude of what has just happened appears to slam into her: she breaks down and cries, at one point calling out “please don’t let my boyfriend go like this”.

In the final minutes, we witness Reynolds’s mounting panic as she realises that her phone battery is running low. She begins to use the feed to call out to her friends and family, stating her location and asking for someone to come and pick her up. Her panic increases and she gets stuck in a loop, repeating statements about the shooting and the details of her whereabouts. She let’s out a guttural wail, and we hear her daughter off camera telling her mother that “I won’t hurt you”.

The ten-minute stream ends with Reynolds’s face in silhouette, intermittently lit up by the red and blue lights of the squad car she is in.

Representing yourself to survive

As the late, great cultural studies scholar Stuart Hall once said, black people have historically been the object rather than the subject of representation. Hall’s point was that the racial inequalities that permeate a society also permeate the representations of that society, and that racial minorities have been denied the power to take charge of how they are represented and how their stories get told. White people (and mainly men) have generally been in control.

The statement I quoted at the top of this article is well-meant, and I agree very much with its sentiment, but it’s inaccurate. The smartphone camera might be new, but cameras aren’t. Representation isn’t. Indeed the camera is a part of the bloody violence that has been meted out against black bodies for centuries. Violence can be physical, but it can also be symbolic.

The scholar Suzanne Kappeler argued that physical and symbolic violence should not be separated, since the latter is all too often a vital tool of the former. Witness the documentation of lynchings in the US in the early 20th century, or more recently the photos that glorified the torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib during the second Iraq war.

This is the context for Reynolds’s live stream of Castile’s death – not so much an act of empowerment as a tactic of survival. Steve Mann’s concept of “sousveillance” – surveillance as done by those usually subject to it themselves – becomes part of everyday reality in the US, with more and more people reaching for their phones to document interactions with the police.

The director of the FBI, James Comey, recently stated that the increase in viral videos is “compromising the ability of officers to do their jobs and contributing to a spike in crime”. Reynolds’ video makes a sobering counter-argument to Comey’s controversial comments.

Her video and others like it record and represent the world in which so many working-class people of colour live. Her shaky, unedited footage provides a way to move beyond the hashtags and the news cycle, and to witness at first hand the fear, panic and distress that comes from living in a country where the colour of your skin determines how likely you are to be shot and killed by a law enforcement officer.

I don’t think Lavish Reynolds was trying to make a film, or even necessarily a statement. At no point in the video do we hear her proclaim that “black lives matter”; at no point does she antagonise the police officers or protest against them. What she was trying to do when she streamed the events of Wednesday July 6 was to stay alive.

With a gun pointed at her, the gun that had just shot her boyfriend, she turned to her phone to document her life in the hope that it would also be her means of “keeping going” in the face of such violence. Scared, shocked and alone, she was reaching out in the hope that she would be seen and heard – and unlike so many before her, she has been.