The memories I have of my paternal grandmother, Máirín Beaumont, mostly involve sweets. She lived with me in Dublin until her death in 1972, when I was five. Our house, a long bungalow by the sea, was divided in two with my grandmother living in the top end and my family (dad, mum and three sisters) occupying the bottom end.

I would regularly flee to the top end to seek refuge and comfort from my maimeó (Irish for granny) following some misdemeanour or an altercation with my older sisters. This resulted in the doling out of sugar cubes or butterscotch sweets from what seemed to be an endless supply hidden away in her kitchen cupboards.

Following her death I cherished these memories. Her presence remained strong in our house as we were surrounded by her furniture, pictures, books and the tokens passed on to us grandchildren as keepsakes (mine was a wooden crocodile that sits on my desk today).

Years later in 1988, when I was researching the history of the Irish women’s movement during the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s as part of my MA in Modern Irish History at University College Dublin (UCD), I was surprised to discover that in her later life my grandmother was a leading member of not one but two of the women’s organisations I was studying: the National University Women’ Graduates Association (NUWGA) and the Irish Countrywomen’s Association (ICA). As I combed through the UCD archives it was wonderful to recognise Máirín in a photograph of past presidents of the Women Graduates Association, where she had served as president from 1951-52.

But a much bigger surprise awaited me. Around 2016 my cousin shared another photo with the family that belonged to his mother. Here, in a grainy sepia image was my grandmother, in her early twenties, smiling directly at the camera. She is perched on a bicycle holding a fishing rod in one hand and a rifle in the other. The shock of seeing my maimeó, someone I had always associated with love and comfort, proudly brandishing a rifle and decked out in her Cumann na mBan (Women’s Council) uniform was profound. This wasn’t the grandmother I remembered.

Cumann na mBan was the Irish women’s republican paramilitary organisation which was set up in 1914, and from 1916 it was affiliated to the Irish Volunteers (later the Irish Republican Army, or IRA). I had been aware Máirín was a member of it in her youth, but I knew little else. I learnt a bit more when I contributed to the entry for my grandmother in the Dictionary of Irish Biography where her involvement in Cumann na mBan is briefly mentioned. Despite this public record, her support of nationalism – which advocated the use of force – was not something we discussed at home. This was not an uncommon experience within Irish families in the wake of the Irish Civil War (1922-23) and during The Troubles in Northern Ireland (1969-1998).

The situation changed earlier this year when I was asked to speak at a UCD symposium about the February 1922 Cumann na mBan convention that led to a spilt in the organisation between members who accepted, or rejected, the 1921 Anglo-Irish treaty. This was the treaty agreed between the British government and representatives of the new Irish Republic which brought about an end to the Irish War of Independence.

The symposium was prompted by the Irish Government’s Decade of Centenaries programme which set out to “ensure that this complex period in our history, including the struggle for independence, the civil war, the foundation of the state, and partition is remembered appropriately, proportionately, respectfully and with sensitivity”. In this new context I felt it was the right time to talk about my grandmother, her role in Cumann na mBan and how she fared in the aftermath of the Irish Civil War. But I was in for another big shock.

Words from the past

Deep in the digital archives of the National Library of Ireland I discovered that maimeó had spoken at the February 1922 convention of Cumann na mBan. None of the family had been aware of this fact. As a member of its executive my grandmother, known by her maiden name Máirín McGavock, made an impassioned speech rejecting the peace treaty with the British government. Here, Máirín told fellow delegates that she could not accept the amendment made by Jennie Wyse Power, founder member of Cumann na mBan, which acknowledged that the treaty “would be a big step along the road” to achieving a republic and that Cumann na mBan members should remain neutral and leave “it to the people to decide the issue”.

This story is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism and is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects to tackle societal and scientific challenges.

Dismissing this compromise Máirín expressed her support for the resolution put forward by Mary MacSwiney that, “the executive of Cumann na mBan reaffirm its allegiance to the Republic of Ireland” and so rejects the treaty. Despite acknowledging that the treaty would bring a pause in the fighting she argued that, “we should not get any breathing space if it means going into the British empire”, and went on to ask:

… are we to stand tied while the life of the country we love is at stake? If we accept this treaty we will never get a republic.

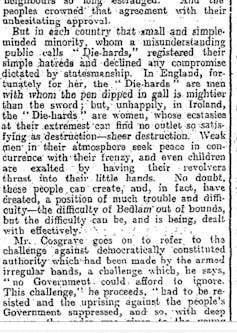

Reading these words it suddenly dawned on me that my own grandmother was one of the anti-treaty women branded as “furies”, “die-hards” and “avid begetters of violence”, by politicians, the Catholic clergy and the press in the wake of the Irish civil war.

Who were the ‘die-hards’?

On January 1 1923 the president of the Irish Executive Council, William T Cosgrave, reflected in his new year’s day speech to the nation that:

… unhappily in Ireland the ‘die-hards’ are women, whose ecstasies at their extremist can find no outlet so satisfying as destruction - sheer destruction.

These words demonising republican women who refused to accept the Anglo-Irish treaty and who supported the anti-treaty side in the Irish civil war, were a common feature of political and public debate in the years following the establishment of the Irish Free State. Sociologist Louise Ryan has written extensively about the negative representation of republican women deemed to have picked the “wrong” side in the civil war.

Embedded in these frequent expressions of nationalist rhetoric, a pre-requisite for nation building, women who rejected the new Irish state were classified as transgressive and disorderly. Such negative portrayals were in sharp contrast to the preferred and dominant representation of Irish women as respectable, law abiding wives and mothers. It was these “true” Irish women, according to Ryan, who embodied the nation and acted as “the keepers of traditional culture”.

The photograph of my grandmother holding a rifle, and her speech to the 1922 Cumann na mBan convention, strongly suggests that she too would have been viewed as one of these “disorderly women” – someone who was a threat to “social order and stability”.

Máirin’s witness statement

Yet, more revelations were to follow. On May 10 1950 my grandmother gave a witness statement to the Irish Bureau of Military History. The bureau was set up in 1947 to gather primary source material for the revolutionary period from 1913 to 1921. In her witness statement Máirín, then aged 56, gave a vivid account of her first encounter with the Irish Volunteers and her subsequent involvement with Cumann na mBan.

It is interesting that she agreed to provide a statement as many anti-treaty activists refused to engage with the bureau, regarding it as a “free state” project. It is also fascinating that she was comfortable documenting her support of physical-force nationalism while at the same time taking on leading roles in the NUWGA and the ICA. This suggests to me that she was proud of her earlier activities as a member of Cumann na mBan and her support for the anti-treaty side.

Reading her witness statement, I wasn’t sure what to think when she recalled that in 1915, as a student living at Dominican Hall, Dublin, she was asked to store two violin cases containing ammunition and revolvers for the Irish Volunteers.

We kept them in our room in the hostel for some time … and they were called for just before we went home for our Easter holidays, 1916.

The timing of this suggests the arms were used in the 1916 Easter Rising. To me this description of my grandmother storing arms was reminiscent of a scene from a classic Hollywood gangster movie – not something I ever imagined my maimeó to be doing.

Máirin said that she was not in Dublin for the Easter Rising as she was spending her university holiday in Belfast. Returning to Dublin after the rising she joined a branch of Cumann na mBan set up in UCD and became an active member serving alongside approximately 75 other women. Among the activities she participated in was fundraising for the families of those imprisoned for their role in the rising and visiting republican prisoners in Dublin. On one occasion she visited Count Plunkett, father of Joseph Plunkett, one of the executed leaders of the Easter Rising who had been incarcerated in Richmond Barracks, Dublin.

Like many members, Máirin was trained in first aid and basic nursing skills. She recounted how from October 1918:

…the bad flu [the 1918 flu pandemic] raged so violently that nurses and doctors were scarce and Cumann na mBan offered the services of its members who had Red Cross training, as voluntary nurses.

She also noted that, “naturally there was no political distinction as regards the people we nursed”. The work was arduous with shifts in the evenings and overnight. In particular my grandmother remembered being on duty the night of November 11 1918 when the Armistice was signed marking the end of the first world war. Violence broke out on the streets of Dublin when the Sinn Féin headquarters was attacked by British sympathisers, which must have been frightening for the nurses on duty that night.

Throughout 1919 and 1920, my grandmother recounted how she continued her “usual” Cumann na mBan activities: drilling (practising military marches and manouvers), first aid and home-nursing. Although she made no direct reference to the War of Independence she did mention that throughout this time she was working as a teacher at Scoil Bhríde, “which was a great centre of political activity and a meeting place for many well-known republicans”. This included Ernest Blythe and Liam Mellows both active members of the Irish Volunteers. Blythe went on to support the Anglo-Irish treaty and was later appointed as a government minister while Mellows opposed the treaty and was executed by firing squad in December 1922 for his part in the Irish civil war.

Máirín described how dispatches were left at the school “to be forwarded through town and country by lines of communication organised by Cumann na mBan”, as the IRA leadership “found the post utterly unsafe” – no doubt due to British army interference. My grandmother explained how these communication lines “consisted of Cumann na mBan girls walking or cycling from branch to branch in the towns and villages”.

In November 1920 Máirín was co-opted onto the executive committee of Cumann na mBan. As a younger member of the executive she was expected at “weekends to hold district council meetings”. Recalling one such meeting, in Bruree, County Limerick, she highlighted the hardship endured during these trips which, it must be remembered, took place at a time of war:

Sometimes we had to spend nights without sleep as we were afraid or unable to get into hotels.

Curfews which were “imposed at a very early hour in some towns where the IRA were active” made it even more difficult for her and fellow organisers who had “of course, to be back at our work on Monday mornings”.

My grandmother was also mixing with many leading republican figures. In another newly discovered family photograph my grandmother is one of the guests attending the August 22 1921 wedding of leading IRA activist Tom Barry and Cumann na mBan executive member Leslie Price, at Vaughan’s Hotel, Dublin. This wedding photograph is a who’s who of Irish political life and my grandmother is sitting on the far left of the picture. Among the guests seen here is Éamon De Valera, then president of the Dáil and Michael Collins who would lead the pro-treaty provisional government in 1922 before being shot and killed by anti-treaty forces during the Irish civil war.

Women’s rights

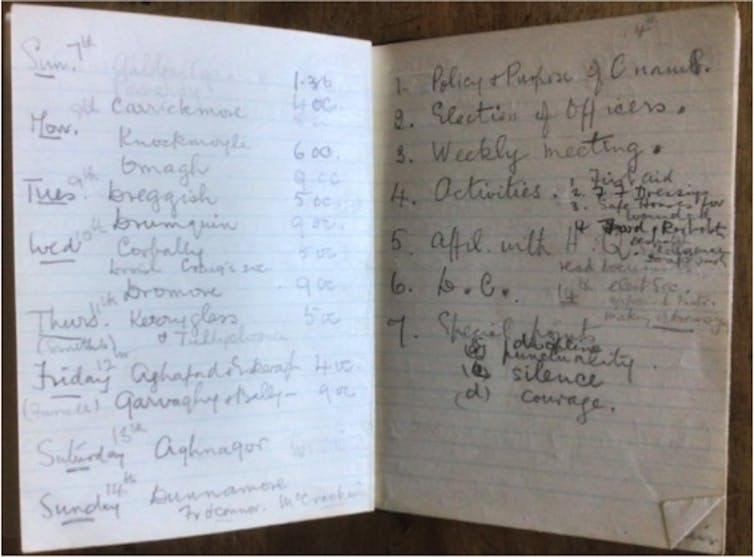

I found a 1921 pocket diary of my grandmother’s among her papers at our home in Dublin that provides further insight into her Cumann na mBan activities at this time. For August 1921 (following the truce in hostilities) an entry indicates that she was travelling through the northern county of Tyrone holding what would appear to be daily recruitment meetings.

The agenda for these meetings outlined the basics required to set up a Cumann na mBan branch. Key activities included: providing first aid, field dressings, food and safe houses for wounded combatants. “Discipline, punctuality, silence and courage” were listed as prerequisites for all new members.

Six months later it was as a member of the Cumann na mBan executive in 1922 that Máirín came to give her speech at the February convention. In confirming her rejection of the treaty she stated:

I am not an enthusiast about women’s rights but I believe that women have as much right to declare their opinion as the men have. We are an independent body of Irishwomen.

She claimed that Cumann na mBan was as entitled to have an opinion on the treaty as the Sinn Féin leadership and members of the Dáil (the Irish parliament). It is clear from her words that she feared the views of Cumann na mBan were being sidelined by those within the republican leadership and provisional government who supported the treaty. Despite her claim not to be enthusiastic about women’s rights she argued that, “women came through things that were perhaps as great, or greater, than the men”, and so were “entitled to declare our opinion”.

As a feminist historian reading these words I am in no doubt that my grandmother was fully cognisant of attempts to “silence” women in public life. Although many may disagree with her stance on the treaty and her willingness to engage in further hostility, I am proud that she wished to defend the right of women to express their views, regardless of the risks involved, on the future of the Irish nation.

The Irish Free State

Máirín’s beliefs, and the stand she was taking, also need to be understood in the context of the time. The Irish Free State was born out of violence, division and turmoil. The island of Ireland had been under British colonial rule for over 800 years, punctuated by a number of attempts – political and revolutionary – to break free from British control. The failed 1916 Easter Rising (an armed insurrection against British rule) and subsequent execution of its leaders, reignited demands for an independent Ireland, free of all ties to the United Kingdom and the British empire.

The part played by Cumann na mBan in the Easter Rebellion was significant. This went beyond the activities of a number of now very well known women. Included in this select group is Constance Markievicz, who in 1918 became the first woman elected as a Member of Parliament to Westminster, although as a republican she refused to take her seat. Historians Margaret Ward, Sínead McCoole, Cal McCarthy and Mary McAuliffe, among others, have shared the stories and documented the experiences of around 200 “ordinary” women who took part in the rising.

They came from different walks of life and included teachers, nurses, students, trade unionists, feminist activists and factory workers. These women were active in roles as varied as snipers, cooks, first-aiders and couriers. After six days of fierce fighting the Easter Rising was suppressed, leaving some 500 dead and Dublin city centre in ruins.

Three years after the rising violence erupted once again with the outbreak of the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921). The growing popularity of Sinn Féin, a radical political party calling for full Irish independence, culminated in its winning 73 out of 105 seats for Ireland, in the UK’s December 1918 general election.

Cumann na mBan was instrumental in supporting this election victory with members canvassing locally for Sinn Féin candidates, including my grandmother who supported the election campaign of Sinn Féin member Desmond FitzGerald, who was elected MP for the Dublin Pembroke constituency. The success of Sinn Féin, and the shock defeat of the more moderate Irish Parliamentary Party, who supported devolved government (home rule) for Ireland, marked a step change in Irish politics and Anglo-Irish relations.

From 1919 to 1921 a guerrilla war was waged across Ireland. Atrocities were committed on both sides with an estimated 2,000 deaths.

Just as they had done in 1916, Cumann na mBan members played an active role, and risked their lives, in supporting republican forces during the War of Independence. Across the country, women provided a network of safe houses for IRA men on the run from British forces and acted as intelligence agents and messengers, enabling the sharing of military information between IRA units. One leading member, Kathleen Clarke, recounted how she smuggled £2,000 of gold, strapped about her body, from Limerick to Dublin, thereby avoiding discovery at British checkpoints along the way.

The War of Independence ended in a truce in July 1921, followed by the signing of the Anglo-Irish treaty in December that year. Under the terms of the treaty a 26-county Irish Free State would be established as a self-governing dominion within the British empire. The six-county unionist majority (representing Protestant interests) Northern Ireland State, which remained part of the UK, was also established with its own devolved government sitting in Stormont, Belfast.

On January 7 1922 the Irish parliament voted to approve the treaty by a narrow majority. Taking a pro or anti-treaty stance split the ruling Sinn Féin party. This resulted in the pro-treaty provisional government, led by Michael Collins, being in direct opposition with members of its military wing, the IRA. Civil war followed with two further years of violence and the creation of divisions within Irish families, communities and political life that continue to resonate today.

‘Sister against sister’

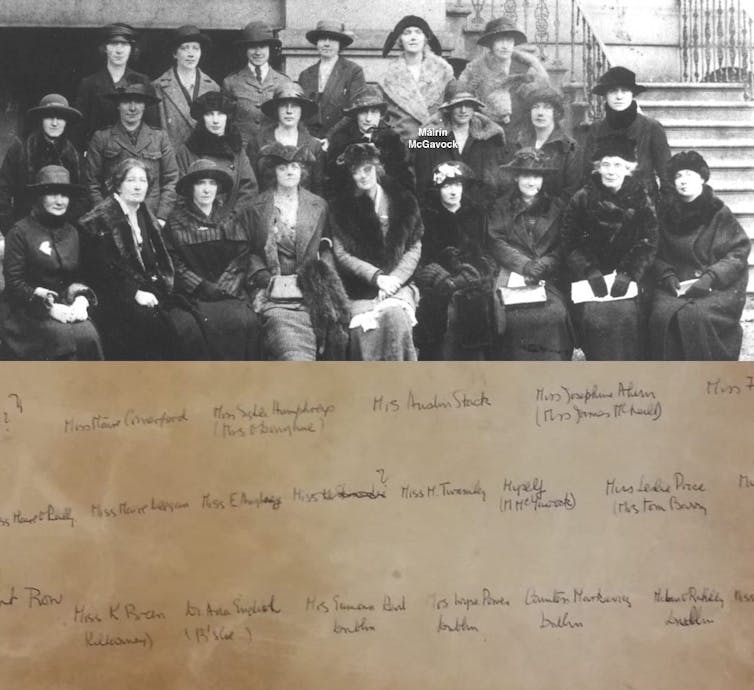

Another photograph was to supply a final surprise about Máirín. It was taken on February 5 1922, four weeks after the Anglo-Irish treaty was officially approved, when Cumann na mBan called a special convention to discuss the terms.

The photo is of the executive committee and shows my grandmother standing in the second row, three from the right, with Constance Markievicz, Mary MacSwiney and Jennie Wyse Power sitting in the front row. I had seen this image before and was convinced the woman whose face was shadowed by the large hat was my grandmother. But I couldn’t be sure until my cousin found Máirín’s own copy among a stack of old family photographs. On the back, she had written out who was who, including herself. I was delighted that I had recognised her.

Around 600 women attended the meeting. Following a debate, during which my grandmother spoke, the executive confirmed its anti-treaty stance and its allegiance to the Republic of Ireland. Leading pro-treaty members, including Power, then split from Cumann na mBan and in March 1922 established a new organisation, Cumann na Saoirse (The League for Freedom).

The Irish Civil War raged on until mid-1923 with a repetition of the guerrilla tactics seen during the War of Independence. Former allies found themselves on opposite sides and prominent leaders were killed or executed, including Michael Collins. In May the anti-treaty IRA agreed to a ceasefire with its fighters returning home.

As John Borgonovo, lecturer in history at University College Cork, has documented, members of Cumann na mBan were active throughout the civil war and were integrated with republican forces around the country. Members established kitchens and first aid dressing stations and in more rural areas acted as look-outs and carried messages and supplies during the fighting.

Borgonovo argues that many members who found themselves on the losing side in the civil war “transitioned to non-violent opposition in the free state”, joined formal political parties or moved “to different forms of agitation or civil engagement” with others “withdrawing from public life altogether”.

Contribution to society

Back in 1988 when I uncovered her roles in the NUWGA and the ICA, I was excited and proud of the fact that Máirín had joined organisations seeking to enhance the lives of women and girls.

Máirín was born on December 7 1894 in Glenarm, County Antrim, one of four daughters of William and Annie McGavock. She was educated at the Catholic Dominican College, Dublin, and then enrolled on the BA Languages Degree at UCD. She was awarded her BA in 1915 followed by an MA in German in 1916. In 1917 she graduated with a higher diploma in education. That same year, she joined the founding staff as a teacher at Scoil Bhríde, an Irish language secondary school for girls in Dublin.

Throughout her life my grandmother remained committed to her twin passions: education and Irish language and literature. As a fluent Irish speaker she was passionate about the language and its importance in safeguarding Irish culture and identity. She remained active in education into middle age in her role as an external examiner in education for the National University of Ireland.

Frustratingly I haven’t yet been able to find any sources indicating what my grandmother was doing during the Irish Civil War. What I do know is that in 1923 she married my grandfather, Sean Beaumont, a lecturer and founder of An t-Éireannach newspaper and they went on to have three children, Máire in 1925, Helen in 1927, and my dad Piaras in 1933. She continued to work as an external examiner following the birth of her children and at the same time became active in a number of civil society associations, including the Dublin Playgrounds Committee which oversaw the provision of child guidance, home visiting, playgrounds and nurseries to less well-off families.

I was thrilled to learn that in the 1950s she was elected president of the NUWGA, following in the footsteps of significant Irish women including: Alice Oldham, and professors Mary Hayden, Agnes O’Farrelly and Mary Macken. From the 1920s the NUWGA participated in a number of high profile campaigns to safeguard the rights of women. This included protesting against a marriage bar, which compelled women to resign their jobs on getting married, protecting the right of women to serve on juries and campaigning against discriminatory gender clauses in the draft 1937 Irish Constitution.

Having the opportunity to research the life story of my grandmother has transformed how I think about her, and the other women branded as furies and die-hards. Regardless of the negative portrayals, my grandmother did make a significant and meaningful contribution to Irish society.

The young woman smiling out at me from that old photograph, fully committed to the fight for an independent Ireland, survived the turmoil of the revolutionary period. She went on to make her mark in the new Irish state through her role as a housewife, teacher, activist and promoter of the Irish language. She did this despite being on the “losing side” and maintaining her life long objection to the Anglo-Irish treaty.

I now have a much better understanding of my grandmother and feel so much more connected to her. It is amazing that she was a part of the histories of female activism I have been researching and writing about for the past 34 years. The success of the Decade of Centenaries is making space for all the histories of the Irish revolution. This ensures we remember everyone who has contributed, including the women branded as furies and the die-hards.

For you: more from our Insights series:

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.