The Conversation is running a series of explainers on key figures in Australian political history, examining how they changed the country and political debate. You can read the rest of the series here.

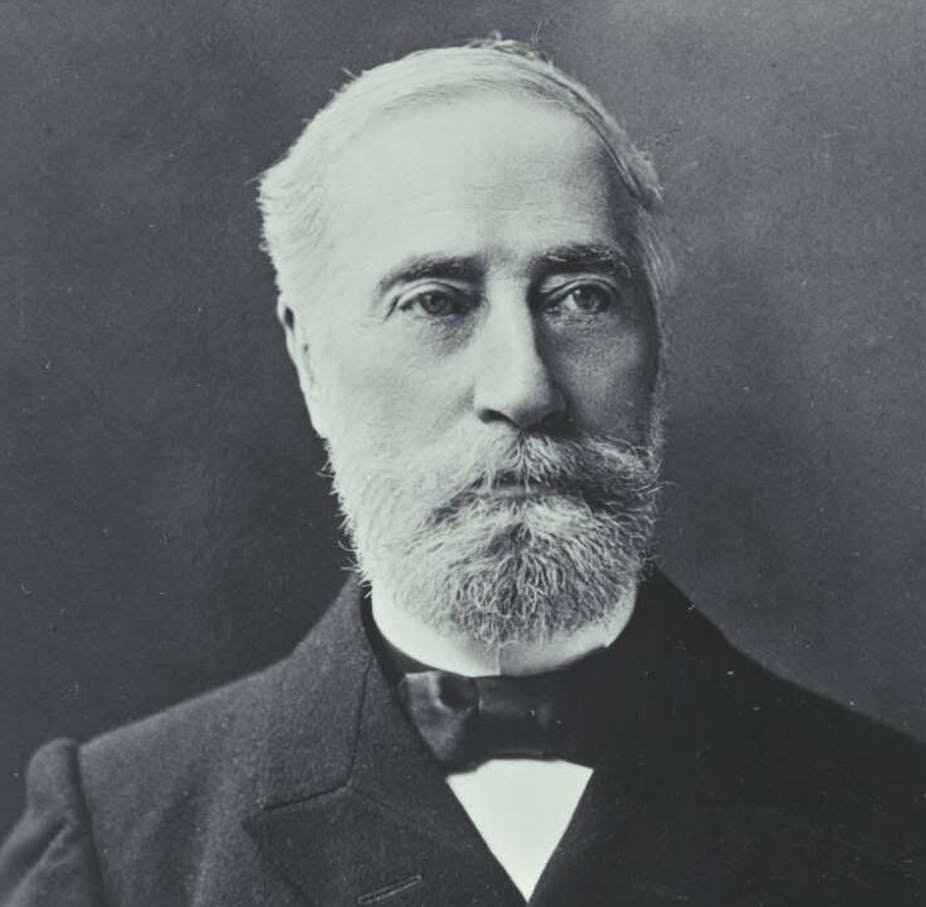

You may never have heard of Graham Berry, but he was one of the most creative and controversial Australian politicians of the colonial era. Born in 1822, he was three times the premier of Victoria, but he is now almost unknown. He should be recalled for his daring and fascinating career, but even more for an enduring influence on the nation’s politics.

Berry’s significance lies partly in his identity and appeal. The son of a servant, he was apprenticed as a linen draper aged 11. He emigrated from England to Victoria during the gold rush of the 1850s, setting up as a grocer in the Melbourne suburb of Prahran.

The Australian colonies were unusually precocious in their extension of democratic rights to working-class men, and Berry was among the first to exploit these opportunities. But his opponents mocked him for his Cockney accent and his low status: “tradesmen” were still widely thought ill-suited to high office.

As I detail in my book about him, Berry responded by attacking the “snobbery” of his opponents and the self-interest of squatters and merchants. He proudly declared his identity as the “embodiment of human labour”. His supporters called him a “self-made man”.

The rhetorical appeals worked. Berry blazed a path for the language of “class” to play a central role in Australian democracy.

The grocer-turned-politician was the leader of a movement for “protectionism”. He argued taxes should be applied to certain categories of imported goods, especially manufactured goods. This would stimulate new industries, he said, and create good jobs at high wages.

Leading political economists attacked the doctrine. Berry was its most eloquent advocate as a platform speaker, newspaper editor and parliamentarian. He passed the first clearly protectionist tariff as Victorian treasurer in the early 1870s. He entrenched the system as premier in later decades.

He also travelled to New South Wales to spread the creed, arguing that protection against “cheap and underpaid labour” provided an impetus to national unity. Berry called the federation of the Australian colonies behind a great tariff wall “the great dream” of his life.

His protégé, Alfred Deakin, would advance that dream, but Berry’s earlier campaigns were the foundation of later success.

Read more: What Malcolm Turnbull might have learned from Alfred Deakin

Berry also reshaped the practice of politics. He first emerged as a major public figure as an “out of doors” speaker in mass gatherings in central Melbourne at the end of the 1850s. Even when these turned violent – one climaxed in an attack on Parliament House and on several parliamentarians in August 1860 – Berry continued to support the rights of the citizenry to meet “where they liked, when they liked, in as great numbers as they liked”.

He equated “agitation” in the “body politic” with the “circulation of the blood in the human body”. To the extent that Australian democracy is active and contentious, it adheres to a tradition Berry fought to establish.

Berry also considered organisation to be central to political life. In 1877, he founded Australia’s first mass political party, the National Reform and Protection League. That party developed a network of more than 150 branches across Victoria, overseen by a central office. It had a common “platform” (an unfamiliar term at the time), its candidates were pre-selected and its parliamentary members met as a caucus and were expected to vote as a bloc.

As president, Berry campaigned for the party across the colony. This was widely seen as an importation of “American” methods of “stump oratory”. It helped to win Berry a stunning majority in 1877 and inspired widespread emulation. Australia’s “party democracy” begins with Berry.

As premier, Berry’s plans for legislation were frustrated by the power of the upper house, elected at that time by a small number of men who possessed substantial property. Berry sought to reshape the Victorian constitution and break the power of the upper house. The London Times likened its key passages to a “revolution”.

The episode precipitated a political crisis that ran from 1878-81. It generated a wider debate on what democracy should be.

From a contemporary perspective, the limits of Berry’s democratic vision are perhaps most striking: he supported women’s franchise (and voted for an unsuccessful bill in 1873) but did not make gender equality central to his political campaigns.

Read more: Birth of a nation: how Australia empowering women taught the world a lesson

He supported the claims of Aboriginal people at the Coranderrk reserve against the attacks of the Aborigines Protection Board, but he also supported the so-called “Half-Caste Act”, which helped to threaten and fracture Aboriginal communities across the colony. Berry showed no interest in Aboriginal political organisation or capacity for self-government.

Berry also understood “protection” in racial terms and sought to exclude Chinese people from the colony.

These policies exerted a considerable influence on later Australian politics.

Recognising and examining these significant limits, contemporary democrats can nonetheless draw inspiration from other aspects of Berry’s career: a driving determination; a refusal to be bound by convention; and an understanding of democracy as an incomplete project, never a settled state.

Those frustrated by the limits of our own democracy might profit from a close examination of Berry’s life.