In February 2016, Guatemalan women survivors and the alliance of organisations supporting them successfully prosecuted two former members of the Guatemalan military for domestic and sexual slavery in the groundbreaking Sepur Zarco trial. The trial marked the first time a national court has prosecuted members of its own military for these crimes. It was an historic achievement in the fight to stop violence against women and secure justice for wartime sexual violence.

And yet, two years later, the Guatemalan government has not carried out most of the collective reparations measures ordered by the court. In large part this is because the main cause of the violence – a dispute over land that historically belonged to the Maya Q’eqchi people – has still not been resolved, even centuries after it began.

Maya communities were first displaced by Spanish colonisation starting in the 16th century, and then displaced again in the mid-to-late 19th and early 20th century. Keen to attract foreign investment, the Guatemalan government encouraged European settlers to establish plantations on land expropriated from Maya communities and the Catholic Church. To this day, many Maya people do not have title to the land they live on, much of which is dominated by plantations growing coffee, sugar, bananas and palms for oil.

But they have been fighting back. I myself have been following the struggle centred on the dusty north-eastern village of Sepur Zarco – a case that pulls together all the threads of what has happened in Guatemala in the last several decades.

The long haul

Local indigenous people have been campaigning to settle on and get legal title to unused land in Sepur Zarco since the early 1950s when the social democratic government of Jacobo Arbenz passed a law to redistribute uncultivated land from the largest landowners to landless peasants. The land concerned included unused land held by the United Fruit Company, a US banana company with close links to the Eisenhower administration – the company disputed the compensation offered to it by the Guatemalan government, and demanded a much larger sum.

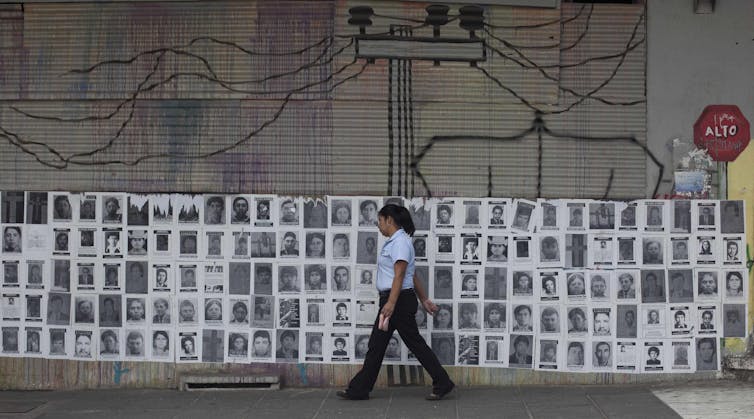

In the end, the land reform was stymied by a CIA-sponsored military coup in 1954. That coup in turn sparked Guatemala’s bloody civil war which lasted until 1996. A post-war UN-led Truth Commission Report concluded that during the conflict, an estimated 200,000 people were killed or disappeared, that rape was commonly used as a weapon of war, and that the Guatemalan state bore responsibility for the majority of the atrocities. It also concluded that agents of the state committed acts of genocide, since 83% of their victims were Maya and most of the conflict’s 626 documented massacres were of Maya communities.

Most of these massacres were committed in 1982-83 under the 17-month rule of recently deceased dictator, Efrain Rios Montt. Rios Montt took power in a coup, and was then removed by another. He was eventually prosecuted by the Guatemalan Supreme Court in 2013 and found guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity. His trial featured testimonies of rape and sexual violence committed against Maya Ixil women, which were included to show that sexual violence was part of the genocide.

However, just ten days after his verdict, the Guatemalan Constitutional Court annulled the trial on procedural grounds after sustained pressure from powerful sectors of Guatemala’s economy and society.

At the time of his death, Rios Montt was once again being prosecuted for genocide – but this time the trial was taking place with special provisions made to allow for his diagnosed dementia. Rios Montt was in office during the time that the crimes committed at the Sepur Zarco base were committed, but he was not prosecuted for those crimes in the Sepur Zarco trial.

The violence committed against Sepur Zarco’s women and their families seems to have been a response to their attempts to settle on and get title to the land, particularly in the late 1970s. According to an expert witness in the the Sepur Zarco trial, Juan Carlos Peláez Villalobos, the military was called in and the indigenous peasant farmers were denounced as “subversives”.

Women survivors also pointed to the link between the attempt to get land titles and the violence committed against them and their husbands. “The landowners gave them [the military commissioners] a list of names of men to disappear,” said one of them in her video testimony to the court. “They said we were troublemakers.”

After kidnapping and disappearing the men and burning down their families’ huts, the military forced their wives to work on the military detachment built in the Sepur Zarco community, in 1982. The women were organised into shifts to cook the soldiers’ food and wash their clothing. While at the base, all of them were systematically raped.

Some women fled into the mountains to escape the violence, where they spent up to six years struggling to survive with little shelter or food. Many of their young children perished because of these conditions. The base remained until 1988. Local men suspected of being “subversive” were also tortured there by the military.

No justice without reparations mr

In February 2016, the Guatemalan Supreme Court ruled that two former members of the military were guilty of forced disappearances and crimes against humanity in the forms of domestic and sexual slavery and the murders of one of the women enslaved on the base, along with her two young daughters. The court also held that the Guatemalan state had to provide collective reparations for the benefits of the village of Sepur Zarco and the surrounding villages.

The measures would provide basic social and economic rights frequently denied to Guatemala’s indigenous and rural communities. They also include the construction of the first local high school, a health clinic and a monument to the women’s husbands – but the state will not start the building work so long as Sepur Zarco’s people don’t have legal title to the land.

The Sepur Zarco case shows how seriously a community can be affected for decades, even centuries, by multiple overlapping injustices – from colonial-era crimes to more recent human rights violations. Resolving the resulting problems has proven hugely difficult. But after more than 30 years, the women and supporting organisations – the National Union of Guatemalan Women, Women Transforming the World and the Community Studies and Psychosocial Action Team – are determined to achieve the restorative justice that they have been struggling for all this time.