When released in 1975, Jaws not only transformed the face of cinema, it would also change the way many of us perceived the ocean. We were exposed to a vengeful, human-eating, boat-destroying great white that although fictional, would end up haunting our relationship with sharks for decades to come.

It would appear that the 40-year-old shark is still stalking many of us. The iconic tones of the theme song is still heard by many as they enter the ocean: “Da-dum, Da-dum …” A dorsal fin breaking the surface still encourages imagery reminiscent of a puppy wrestling a chew toy, only with added clouds of crimson and shrills of terror.

Jaws resonated so strongly with audiences because Peter Benchley, author of the original novel, took inspiration from real-life events. Shark incidents did happen and with expanding populations, more and more people were encountering them while enjoying the ocean.

Stories of “rogue” sharks caused headlines that added kindle to the embers of fear that Jaws had started. The shark had quickly become the villain that we loved to hate. Much like the chiming bell of a buoy, the film’s tagline – “Don’t go in the water” – rang loud for many people.

The reality was that even with increased shark accidents the number of annual incidents was low. In 2014, only three people died from shark bites. Dogs, cows, driving and even vending machines would kill more people in 2014 than sharks did.

Yet, without fully understanding the shark, many beaches would employ destructive measures in an attempt to reduce the risks. Gill nets, hunts and shark culls were adopted in an attempt to reduce the risk to ocean users, all of which would end with the death of our new “villain”.

As exposure of shark incidents increased, so did our fascination with this “monster”. While no doubt responsible for the fear felt by most, the film was also a catalyst for progressing scientific research within the field of shark biology.

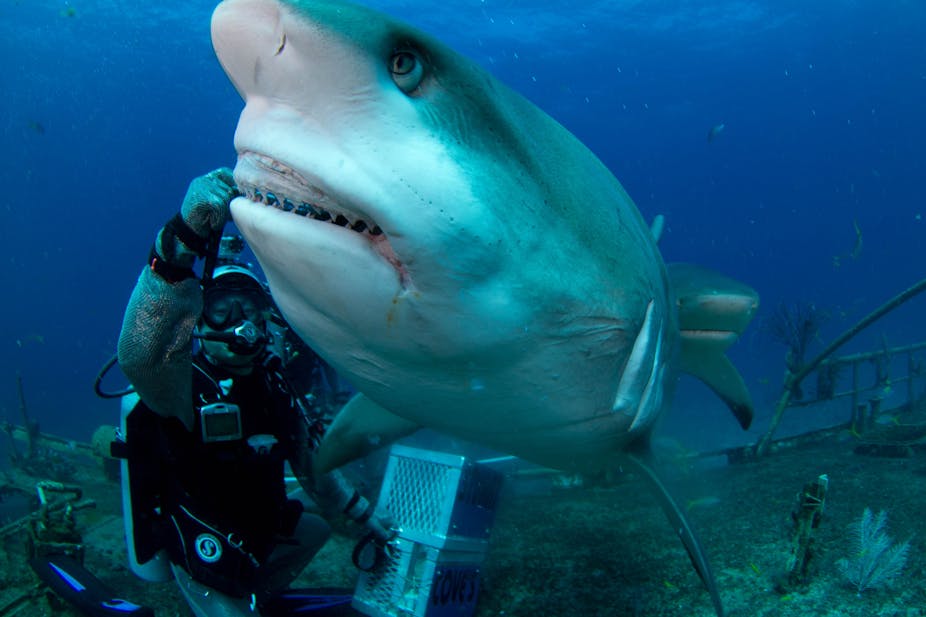

Scientists did go in the water

Primarily set on mitigating the occurrences of shark attacks, we slowly began to unravel the enigmatic world of these “big fish”. Portrayed in the film as an indiscriminate killing machine capable of seeking revenge and sinking our boats, we slowly began to see there was much more behind the shark’s dark, “doll eyes” than first appeared.

Research groups around the world began dedicating their work to uncovering the cryptic behaviour of these animals. We learnt of their incredible feats of transoceanic migrations, complex 3-dimensional movements and intricate population structuring. They weren’t too dissimilar to us with social interactions, learned behaviours, and even feeding preferences. These revelations were made across the shark species, from freshwater to the deep-sea.

Turns out, not all sharks were formidable apex predators and we very quickly realised that few species actually posed any threat to us whatsoever.

Why we need sharks

The most alarming of all scientific discoveries however, would capsize everything we thought we knew about our relationship with sharks.

Sharks are key predators within ocean habitats and are, in turn, vital components within these environments. Removal of sharks from the oceans can have disastrous effects that reverberate throughout an ecosystem.

Unfortunately, sharks were under decline. With post-film popularity in trophy hunting and an on-going global expansion of fisheries, sharks were being removed from the ocean at an unprecedented rate. The fate of many would be in the soup bowls on Asian tables, where a dish called shark fin soup was being consumed on a growing scale.

With estimates of 63 to 273 million sharks being killed every year, the once feared villain was now the imperilled victim.

Despite scientists unanimously warning of the importance and vulnerability of shark populations, many countries are still failing to provide adequate fisheries management and regulatory enforcement to inhibit further declines.

In the 40 years following the release of Jaws, it is quite remarkable the advancements we have made in understanding the ocean and its sharks. Yet, despite these advancements, countries continue to retaliate to shark incidents in much the same way that the residents of Amity Island did in Jaws: with shark hunts and culls.

A recent study that evaluated the kill-based strategies adopted by Western Australia (and other countries), exposed the ineffectiveness of these destructive methods. Instead, hazard mitigation policies should focus on expanding scientific research, developing non-lethal mitigations and further improving education, outreach and public awareness/opinion.

Our relationship with the shark is one riddled with complexities. After four decades of research by people inspired by these animals, education, ecotourism and fisheries regulations are improving. However, fantastical media inaccuracies and economic greed are preventing us from truly escaping the misconceived clutches of one of the ocean’s most misunderstood monsters.