Salvatore “Toto” Riina, once leader of the Sicilian mafia, has died in a prison hospital at the age of 87. In Italy, reaction to his death has been mixed. For me, having studied Italian mafias since the early 1990s, when Riina’s Cosa Nostra was waging war against the Italian state, his death brings a strange sense of restless closure to an important chapter in the history of Italian organised crime.

Riina was born in the hill town of Corleone, and began his career in Cosa Nostra at the age of 19. By the early 1970s, he had become one of the group’s main leaders, imposing his own brutal “mafia model” on the rest of the organisation and eliminating possible rivals.

Like many mafiosi, he had nicknames. He was variously known as “Il capo dei capi” (the boss of all bosses) and “Totò ‘u curtu” (Toto the short one). But it was the moniker “La Belva” (the Beast) which will define his place in Italian postwar history. It serves as a stark reminder of the extensive violence he used to transform the Sicilian mafia from a traditional criminal organisation into a killing machine which adopted a terrorist strategy against its enemies and the state.

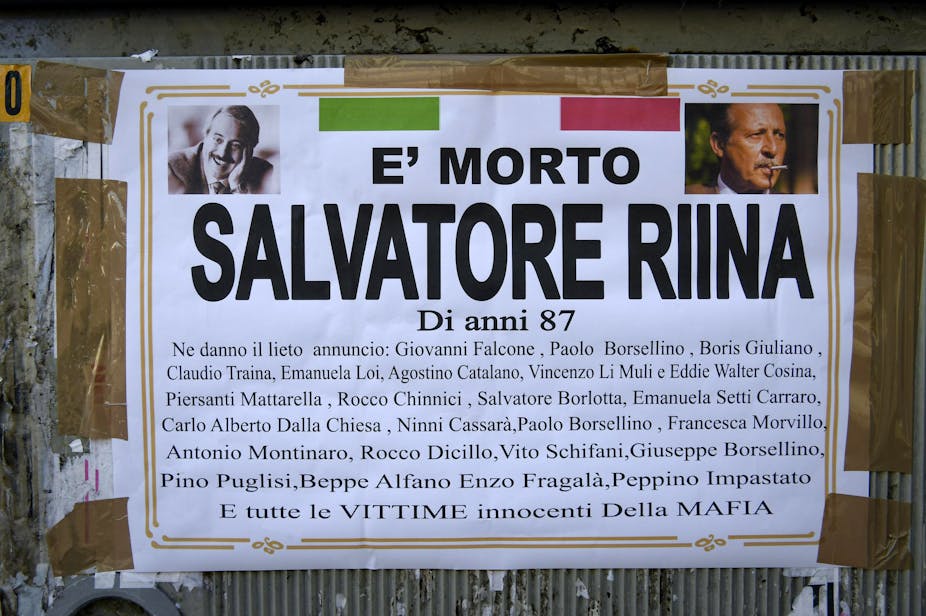

When Riina died, he was serving 26 life sentences for ordering innumerable murders and massacres. Victims included mafia rivals, journalists, businessmen, politicians, police officers, investigators and judges (including Giovanni Falcone, Francesca Morvillo, Paolo Borsellino and Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa).

He imposed cruelty and treachery on all those who got in his way, as well as their innocent relatives, such as the 14-year-old son of mafioso-turned-informant Santino Di Matteo. The boy, Giuseppe, was kidnapped in 1996, and after two years, strangled and his body dissolved in acid, as punishment for his father’s actions. The mother, aunt and a sister of another informant, Francesco Marino Mannoia, were also savagely murdered in 1989.

Riina finally met his match when the brave and extraordinary judge Giovanni Falcone began to investigate the Cosa Nostra in Sicily, Europe and the US. Gus Jones, the only British police officer to have worked with Falcone, told me: “He was a gentleman and the ultimate professional. It was his non confrontational attitude which got him results.”

Falcone (along with his friend and colleague Paolo Borsellino) tried to understand the social, economic and political power of Cosa Nostra. To do this, he understood the importance of following the money trail, but also getting an insider’s perspective of the mafia.

His breakthrough came in 1984, when mafioso and Riina rival, Tommaso Buscetta, asked to talk with him. Falcone recalled in his book Men of Honour:

Before Buscetta we had only a superficial knowledge of the Mafia phenomenon. With him we began to look inside it. He gave us confirmation of its structure, its recruiting methods and its raison d'être. But above all, he gave us a broad, far reaching global vision of the organisation. He gave us the essential keys to the interpretation of the Mafia, a language, a code.

The intimate and respectful rapport that Falcone developed with Buscetta, and the information he collected from him, and other informants, resulted in the Maxi Trial of 1986-92 and the conviction of more than 350 mafia members. This further convinced Falcone of the fundamental importance of implementing a formal Italian state witness protection programme.

Just before Falcone was murdered in 1992 by Riina’s men, a law was passed in 1991 which established such a programme. It gave the state significant tools to fight against the mafia over the last 26 years – at one point there were over 1,200 state witnesses signed up.

When Riina was arrested in 1993 in the centre of Palermo, after 24 years on the run, his associate, Bernardo Provenzano, took up the reigns and adopted a different strategy. The Cosa Nostra attempted a less visible approach, with a drive towards more peaceful criminal activities. Cosa Nostra entered a silent phase.

Mafia minds

Riina however, did not repent, and took many secrets with him to the grave. Among these, probably, the details of Cosa Nostra’s relationship with political parties such as the Christian Democratic party and Forza Italia and with the state. Over the last couple of years, he was regularly intercepted talking with his cellmate about the murder of Judge Falcone and how to deal with the new generation of anti-mafia judges.

So does his own death signal the end of Cosa Nostra? Certainly it marks a moment of frustration for those of us researching and teaching it, who may now never fully understand the secrets and rationale behind the crimes Riina ordered and who his accomplices were.

That said, his decision to adopt such a violent strategy against the Italian state, and his belief that he was outsmarting everyone, can now be seen as perhaps the direct cause of Cosa Nostra’s demise and its ultimate weakening. For in response, the state started to actively engage in the fight against organised crime – and has since kept up that momentum. It can also perhaps help explain the increased power abroad of rivals like the Calabrian Ndrangheta and the Neapolitan Camorra in the 1990s, as Cosa Nostra became distracted by local events.

But Cosa Nostra and Italian mafias are not finished. Far from it, in fact. As Falcone himself warned:

Let us not forget that the Mafia is the most agile and pragmatic organisation imaginable, compared to our social institutions and to society in general.

Cosa Nostra, like the Calabrian Ndrangheta, the Neapolitan Camorra and the Pugliese Sacra Corona Unità, is already onto the next thing. They have a new generation of leaders, modern business activities, hidden associates and profitable political projects. For now, the Italian state must prevent Riina from being seen as a martyr – and its law enforcement agencies, together with their international colleagues, must be as vigilant as ever.