Recently, quite by accident while looking for something completely different – information on British military music in the Napoleonic era, to be precise – I discovered a remarkable discussion of homosexuality in the diary of an early 19th-century Yorkshire farmer.

Reflecting on reports of the recent execution of a naval surgeon for sodomy, Matthew Tomlinson wrote on January 14 1810:

It appears a paradox to me, how men, who are men, shou’d possess such a passion; and more particularly so, if it is their nature from childhood (as I am informed it is) – If they feel such an inclination, and propensity, at that certain time of life when youth genders [develops] into manhood; it must then be considered as natural otherwise, as a defect in nature […] it seems cruel to punish that defect with death.

This inference sparked solemn religious introspection, as Tomlinson struggled to understand how a just creator could countenance such severe penalties for a God-given trait:

It must seem strange indeed that God Almighty shou’d make a being, with such a nature; or such a defect in nature; and at the same time make a decree that if that being whome he had formed, shou’d at any time follow the dictates of that Nature with which he was formed he shou’d be punished with death.

As part of my doctoral research I’ve investigated many cases that reflect attitudes to sexuality in the armed forces of the period. There were many accusations of drummers working as prostitutes or rumours of their sexual involvement with officers. But this was something quite different.

A 45-year-old tenant farmer, Tomlinson resided at Dog House Farm on the Lupset Hall estate, a mile south-west of Wakefield in Yorkshire. His voluminous diaries chronicle local Luddite disturbances, agricultural life, and his attempts to find a second soulmate after the demise of his first wife.

A former Methodist, Tomlinson was an observant but ecumenical Christian – he wrote extensively on faith, love, death, and the political and economic affairs of his day. Although a few historians, including Katrina Navickas, have quoted from Tomlinson’s diaries in the past, his meditations on homosexuality have never previously been brought to light.

A chance discovery

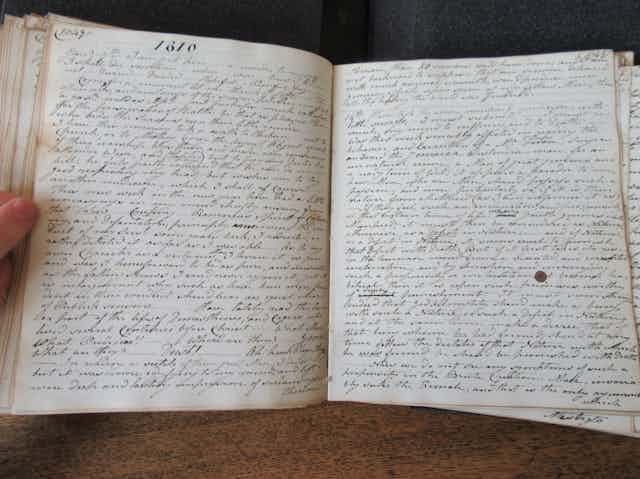

I identified the passage quite by chance. Returning by train from a 2018 conference on military history in Leeds, I decided to stop in Wakefield on a whim to view Tomlinson’s diaries in the local museum, having noticed colourful quotations from them in a book by Ellen Gibson Wilson on the Yorkshire election of 1807.

As it turned out, the diaries had little to say about military music – Tomlinson was disdainful of patriotic pageantry – but his reflections on homosexuality, which I spotted while paging through the journals, stood out to me as striking and unusual for the time. I later decided to reach out to specialists on 18th and 19th-century sexuality to discern if my instincts were correct. UK-based American researcher Rictor Norton and Fara Dabhoiwala of Princeton University both generously shared their expertise, confirming the rarity and significance of my discovery.

The argument that same-sex relations were natural and innocuous was occasionally advanced in 18th-century England (in a 1749 tract by Thomas Cannon for instance), while Enlightenment thinking on individual liberties and legal reform spurred calls for Britain to emulate its continental counterparts by abolishing the death penalty for homosexual acts.

Some men and women of the time who engaged in same-sex relationships viewed their sexual orientation as innate: Halifax landowner Anne Lister justified her lesbian feelings as “natural” and “instinctive” in her diary in 1823. Utilitarian philosopher and social reformer Jeremy Bentham even expressed support for the decriminalisation of homosexuality in various writings from the 1770s to the 1820s, contending that sodomy statutes stemmed from “no other foundation than prejudice”.

Read more: Gentleman Jack: a gripping 19th-century tale of one woman's bravery in sex and politics

But he did not dare publish such radical views. After all, this was an era when spreading false allegations of same-sex proclivities was considered by some commentators as akin to committing murder, such was the reputational ruin faced by the accused.

‘Crime’ and punishment

In an age of rampant persecution, homosexual men in Georgian Britain were regularly executed or publicly disgraced, brutalised by hostile crowds in public pillories and forced into exile overseas. Tomlinson’s own meditations appear in his private diary, an intimate record of his thoughts not intended for a wider audience.

While Tomlinson’s writings reflect the opinions of only one man, the phrasing implies that his comments were informed by the views of others. This exciting new evidence perhaps complicates and enriches our understanding of historical attitudes towards sexuality, suggesting that the revolutionary conception of same-sex attraction as a natural human tendency, discernible from adolescence and deserving of acceptance, was mooted within the social circles of a Yorkshire farmer during the reign of George III.

Tomlinson’s reflections were prompted by reports of the court-martial and execution of naval surgeon James Nehemiah Taylor, who was hanged from the yard-arm of HMS Jamaica on December 26 1809 for committing sodomy with his young servant. Newspapers across Britain and Ireland published accounts of the case, reminding their burgeoning readerships of the draconian state penalties for homosexual behaviour.

Contemporary media reporting on sodomy cases, often couched in the language of moral panic, both reflected and reinforced social stigma against same-sex intimacy. But Tomlinson’s writings suggests that not all readers uncritically accepted the homophobic assumptions they encountered in the press. Disheartened by the ignominious demise of an accomplished medical man, the diarist questioned the justice of Taylor’s punishment and debated whether so-called “unnatural” acts were truly deserving of such an appellation.

But Tomlinson’s musings are still very much the product of his time. Although the diarist seriously considered the proposition that sexual orientation was innate, he did not unequivocally endorse it. Erroneously believing homosexual behaviour was unknown among animals, Tomlinson still allowed for the possibility that homosexuality might be a choice and therefore (in his view) deserving of punishment, suggesting that capital sentences for sodomy be replaced by the still gruesome alternative of castration.

Wider implications

Tomlinson’s meditations thus prove ultimately inconclusive, but nonetheless provide rare and historically valuable insight into the efforts of an ordinary person of faith to grapple with questions of sexual ethics more than two centuries ago. His comments anticipate many of the arguments deployed successfully by the LGBT+ and marriage equality movements in recent decades to promote acceptance of sexual diversity.

Tomlinson’s remarkable reflections suggest that recognisably modern conceptions of human sexuality were circulating in British society more widely – and at an earlier date – than commonly assumed.

I am thrilled to be able to share this exciting and historically significant new evidence with a wider audience, particularly during LGBT+ History Month. I hope the find will inspire other historians and students to engage more fully with the rich collections available in local and regional archives, while serving as a reminder of the serendipity inherent in historical research.

Sometimes the most interesting and important discoveries are the ones you weren’t even looking for.

This is an edited version of an article published by the University of Oxford’s arts blog.