How will climate change remake our world in the 21st century? Will we be able to adapt and survive? As with many things, the past is a good guide for the future. Humans have experienced climate changes in the past that have transformed their environment – studying their response could tell us something about our own fate.

Human populations and cultures died out and were replaced throughout Eurasia during the last 500,000 years. How and why one prehistoric population displaced another is unclear, but these ancient people were exposed to climate changes that changed their natural environment in turn.

We looked at the region around Lyon, France, and imagined how Stone Age hunter gatherers 30,000-50,000 years ago would have fared as the world around them changed. Here, as elsewhere in Eurasia during colder periods, the environment would have shifted towards tundra-like vegetation – vast, open habitats that may have been best suited for running down prey while hunting. When the climate warmed for a few centuries, trees would have spread – creating dense woods which favour hunting methods involving ambush.

How these changes affected a population’s hunting behaviour could have decided whether they prospered, were forced to migrate, or even died out. The ability of hunter gatherers to detect prey at different distances and in different environments would have decided who dominated and who was displaced.

Read more: Humans are not off the hook for extinctions of large herbivores – then or now

Short of building a time machine, finding out how prehistoric people responded to climate change could only be possible by recreating their worlds as virtual environments. Here, researchers could control the mix and density of vegetation and enlist modern humans to explore them and see how they fared finding prey.

Surviving in the virtual Stone Age

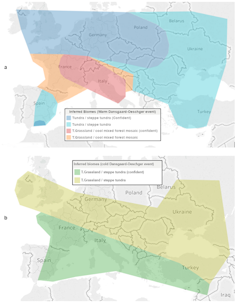

We designed a video game environment and asked volunteers to find red deer in it. The world they explored changed to scrub and grassland as the climate cooled and thick forest as it warmed.

The participants could spot red deer at a greater distance in grassland than in woodland, when the density of vegetation was the same. As vegetation grew thicker they struggled to detect prey at greater distances in both environments, but more so in woodland. Prehistoric people would have faced similar struggles as the climate warmed, but there’s an interesting pattern that tells us something about human responses to change.

Creeping environmental change didn’t affect deer spotting performance in the experiment until a certain threshold of forest had given way to grassland, or vice-versa. Suddenly, after the landscape was more than 30% forested, participants were significantly less able to spot deer at greater distances. As an open environment became more wooded, this could have been the tipping point at which running down prey became a less viable strategy, and hunters had to switch to ambush.

This is likely the critical moment at which ancient populations were forced to change their hunting habits, relocate to areas more favourable for their existing techniques, or face local extinction. As the modern climate warms and ecosystems change, our own survival could become threatened by these sudden tipping points.

The effects of climate change on human populations may not be intuitive. Our lifestyles may seem to continue working just fine up until a certain point. But that moment of crisis, when it does arrive, will often dictate the outcome – adapt, move or die.