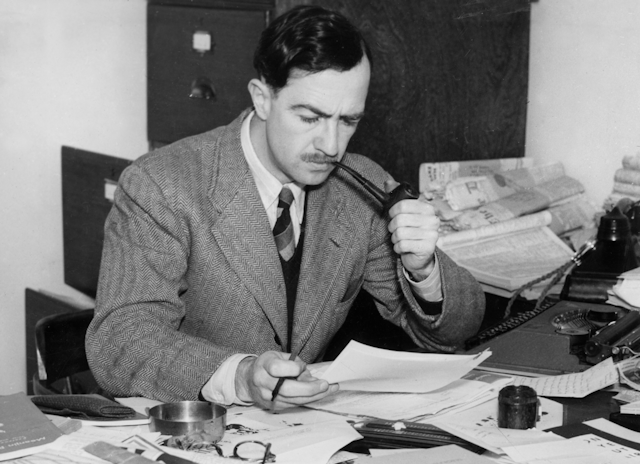

The cover of Jim Davidson’s Emperors in Lilliput juxtaposes a photograph of Meanjin’s Clem Christesen smoking a pipe with a picture of Overland’s Stephen Murray-Smith lighting his.

The design conveys Davidson’s focus on the parallels between the two editors, each of whom founded and presided over a little magazine for a remarkable 34 years. But the mirrored images also highlight the gulf between a past in which Men of Letters might casually puff on their briars and a present in which pipe-smoking editors constitute a faintly risible cliché.

Review: Emperors in Lilliput – Jim Davidson (Miegunyah Press).

Davidson’s study provides, then, an excavation of a vanished world, an archaeological dig into the miniature kingdoms over which Christesen and Murray-Smith once ruled, both of which rested on a distinctive literary nationalism.

“The culture of a country is the essence of nationality,” Christesen explained in an early radio broadcast, “the permanent element of a nation.”

He launched Meanjin amid the total war of 1940. With a Japanese invasion seemingly imminent, the writer Randolph Bedford dismissed a new literary magazine as a waste of much-needed ink: intellectuals should, he said, be “digging post holes” rather than scribbling poems.

Meanjin’s supporters, on the other hand, saw high culture as constitutive of national consciousness, an idea traceable back as least as far as the Enlightenment. Hume, for instance, thought “a few eminent and refined geniuses” would shape a “whole people” by their “taste and knowledge”.

This idea was considerably sharpened by the first world war. As Chris Baldick explains in his classic The Social Mission of English Criticism, literary scholars promoted great writing as fostering “the national heritage and all that was precious in it, against the threat of its destruction by the barbaric Hun”. With Christianity losing its power, the literary canon offered an alternative foundation for the nation state – so much so that, in 1921, Oxford’s George Sampson could declare reading “not a routine but a religion […] almost sacramental”.

The sense of good books superseding the Good Book as the source of national cohesion spurred on Christesen and his allies. Vance Palmer identified resistance to the Japanese with an “Australia of the spirit”. An early Christesen editorial made the same point – albeit warning that the country’s roots were “embedded in shallow sand and rubbish” and thus required a serious literary watering.

War, in other words, made poetry more necessary, rather than less.

Literary nationalism and spiritual unity

Nationalism provided an external justification for Christesen’s preoccupations, rendering novels and poems not esoteric diversions but interventions of considerable public importance. Crucially, though, it did so without reducing literature to a mere cipher or proxy. Authors forged spiritual unity with their imaginative power, so national identity depended not merely on books, but on great books. On that basis, Meanjin’s literary nationalism stressed the literary as much as the nationalism: as Davidson says, “quality” remained Christesen’s watchword.

Overland evolved in a quite different fashion. Like Christesen, Stephen Murray-Smith came from a respectable conservative family. After military service in New Guinea, he studied at the University of Melbourne, a hotbed of postwar radicalisation that induced him to move from the Liberal Party to the ALP to the Communist Party of Australia (CPA), all within the space of year.

Local communism emerged from the war considerably strengthened by the reflected glory of the Red Army. Having long since abandoned proletarian revolution, CPA politics centred on the dream of a Popular Front: a patriotic alliance between the working class and the liberal wing of the bourgeoisie.

The orientation lent particular significance to its cultural endeavours. The party embraced what it called a “progressive nationalism”, describing local democratic traditions as menaced by capitalists in hock to foreign imperialists. Accordingly, the CPA ran bookshops throughout the country, launched a subscription-based distribution service known as the Australasian Book Society, and encouraged would-be authors of democratic nationalist literature to join the Realist Writers Group, whose newsletter Murray-Smith edited from 1952.

The CPA’s advocacy of a now desperately unfashionable “socialist realism” could, perhaps, be framed in contemporary terms as an effort to promote more diverse representation in a publishing industry that almost entirely excluded working class people.

In some respects, it succeeded admirably, constructing a parallel literary infrastructure based on the trade unions. It created an alternative canon of left-wing writers that included the likes of Frank Hardy, Dorothy Hewett, Jean Devanny and John Morrison.

Yet its failures could also be given a modern gloss. An emphasis on inspirational portrayals of “positive heroes” supposedly arising from authors’ “lived experience” fostered an aesthetic conservatism that privileged didactic content over formal experiment. In his study Writing in Hope and Fear, John McLaren describes how the Sydney Realist Writers Group critiqued a Frank Hardy story called Death of a Unionist:

Members of the group objected that the characters in the story were not ‘typical’, the husband Bill showed a ‘bad attitude’ to his wife and had an anarchic attitude to union discipline, and the story left it unclear whether the woman gave away her baby for economic or domestic reasons.

The party developed a kind of “sensitivity reading”, in which apparatchiks assessed how accurately a given book represented working class struggles: disapproval of Sally and Frank Banister’s novel Tossed and Blown led, for instance, to weeks of denunciations in the CPA’s newspaper Tribune, in a prolonged and public cancellation.

Read more: Judith Wright, an activist poet who was ahead of her time

A civilising pursuit

Overland appeared in 1954. Initially advertised as an extension of the Realist Writers Group newsletter, it was registered in the name of its editor, so when Murray-Smith exited the party after the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1958, Overland came with him.

The introduction to the 1965 anthology An Overland Muster illustrates how Murray-Smith’s editorial perspective developed. It argued that:

Firstly, that writing was not confined simply to the best that had been said, written or thought in the world, [but] that there were all sorts of traditions, and not just a ‘great’ one; secondly, that other things being equal, writing dealing with our local reality, Australia and our jobs and our politics and our history, and if you like, our beaches, would be meaningful in a way that ‘better’ writing more removed from us was not meaningful.

The passage retained the CPA’s commitment to a plebeian nationalism, defined, in some senses at least, against a traditional Anglophile elite. But Murray-Smith now rejected the conceptual apparatus of socialist realism, insisting that Overland wanted to be “broader, more humorous, more conscious of literary standards, and less dogmatic in every way”. As he put it, in a later bald formulation, “we are not particularly interested in stories-with-a-social-message”.

By abandoning a conception of literature as a direct political intervention, Murray-Smith moved to a version of cultural nationalism much closer to Christesen’s, so much so that Frank Hardy could sniff about Overland becoming “a kind of poor man’s Meanjin”. As Davidson says, Murray-Smith maintained a focus on authenticity, while Christesen remained more literary, but “a good many people subscribed to both magazines; writers eager for publication, happily wrote for both of them […] in effect, they functioned conjointly”.

Their complementary success underscores the tremendous advantages of nationalism as a strategic orientation.

By the 1930s, Terry Eagleton says, the re-invention of literature as a semi-spiritual social glue allowed intellectuals to present English literature as “not only a subject worth studying, but the supremely civilizing pursuit, the spiritual essence of the social formation”. That conviction – a sense that literature mattered fundamentally to the nation – sustained Christesen and Murray-Smith running their tiny magazines for 34 years, a tenure that Davidson describes (correctly, in my view) as “almost inconceivable today”.

Christesen donated the equivalent of $400,000 of his own money to keep Meanjin alive; even his flaws (in an extraordinary chapter, Davidson describes his own harrowing experience as Meanjin’s second editor, constantly undermined by its controlling founder) stemmed from his unshakeable belief in his mission.

The collapse of the nationalist paradigm

Yet Emperors in Lilliput also allows us to understand how the nationalist paradigm collapsed. The later incarnations of Meanjin and Overland were, Davidson says, “often dismissed by much of the reading public as too self-consciously Australian, exercises in gumnutry”.

That’s not surprising. During the Cold War, a deep anti-Americanism underpinned the CPA’s cultural interventions, with party publications calling, for instance, for ruthless censorship of US comic books. The Australasian Book Society’s Bill Wannan urged Overland to pit its “aggressive Australianism” against “the rubbish coming in from overseas”. By and large, the journal did, mounting, through the entirety of Murray-Smith’s editorship, a rearguard defence of Australian folk traditions against comics, television, rock music and the like.

Christesen’s commitment to a nationalism underpinned by high culture more-or-less mandated an opposition to US-based culture industries, despite his deep engagement with American literature. By the the 1950s, he, too, was denouncing the “enormous quantity of sub-normal trash” arriving from overseas and urging Australia “to protect its own culture from being perverted and corrupted by debased forms of a foreign culture”. From the perspective of a 21st century in which Warner Brothers and DC reign supreme, a belief in a literary Border Force capable of excluding American superheroes seems quixotic, even perverse.

As far back as 1848, Marx had described the inexorability of cultural globalisation. The Communist Manifesto explained how “individual creation of individual nations [became] common property”. For Marx, the world market’s tendency to undermine “national one-sidedness and narrow-mindedness” made cultural autarky not only impossible but profoundly reactionary.

The development of Meanjin and Overland illustrates the point. Meanjin took its name from a Turrbal word for the spiky promontory on which Brisbane had been built. The magazine used as its colophon a boy holding a goanna and a boomerang. An early edition contained an A.P. Elkin article entitled Steps into the Dream Time. Yet Meanjin, like almost all the writers it published, took it for granted that a national culture would be European.

In a presentation in 1966, Christesen reduced Indigenous Australia to a cautionary tale, a warning as to where an insufficiently vigorous culture might lead. “An Australian literary editor,” he explained,

is confronted by a sort of vast cultural Simpson desert. A few literate natives huddle beneath ragged ghost gums or brigalows near brackish billabongs and soak holes. For the most part they live solitary lives, mumble to themselves, go on random walkabout, but certainly there is little communication in any recognisably civilised sense between them.

The Communist Party had backed Aboriginal struggles from as early as the 1920s and, as leftists, Murray-Smith and his comrades stood considerably in advance of the white mainstream. Davidson describes how Overland published a “cluster of articles on Indigenous matters”, including an insider account of the NSW Freedom Ride of 1965.

Yet it is difficult not to notice how much the “temper democratic, bias Australian” slogan that adorned the Overland masthead sounds like a Hansonite catchphrase. The comparison might be unfair – Murray-Smith chose the phrase because in the 1950s conservatives identified with the British empire. But the quotation came from Joseph Furphy’s novel Such is Life (1897) – and Furphy elsewhere explained how in “all the rugged prose of life there runs a strain of poetry, and the name of the poem is White Australia”.

In a colonial settler state, the boundary policing of literary nationalism could not help but foster a racialisation of culture, even among self-identified progressives.

Indeed, one of the revelations in Davidson’s account involves the markedly right-wing jag Murray-Smith took in later years. A student demonstration against the racial IQ theorists Hens Ensenck and Arthur Jensen appalled him so much that he briefly contemplated an “alliance with the authoritarian right to guarantee the order without which we cannot function”. He considered the Whitlam government “more disastrous than most of us on the Left are willing to admit”. He became vice-president of the Anti-Metric Society, judged the foundation of the Communist Party “the biggest tragedy in Australian politics”, and suggested that a proposed new school curriculum should centre on Latin, typing, the Bible, and “perhaps car mechanics”.

Literature and activism

Murray-Smith’s late conservatism adds an exclamation point to Davidson’s key contention that the end of the two men’s tenure signalled the expiry of a certain model of literary editorship.

So what, we might ask, has replaced it? Consider the rhetorical strategies by which literary organisations, including magazines, defend their existence today.

When Murray-Smith died in 1988, the Labor Party had already embraced the neoliberalism that was sweeping the world. One facet of that was the reconceptualization of the arts as first and foremost an industry, justified by the extent to which it contributes to GDP. Of necessity, as Alison Croggon writes, “artists and cultural organisations [were] forced to justify themselves in languages and according to criteria that have almost nothing to do with art”.

As Croggon implies, this was a venture doomed from the start. You can tot up the not-inconsiderable number of people employed directly and indirectly by the culture industries, but that does not provide a vocabulary to assess the activity those people consider important. To put the issue another way, if the market adjudicates aesthetics, J.K. Rowling matters more than any poet who ever lived.

Not surprisingly, desperate writers push back against the neoliberal paradigm by invoking an old-style literary nationalism, not least because its assumptions are baked into the infrastructure of arts funding. Yet, though slogans about “telling Australian stories” emerge almost reflexively, they no longer possess much rhetorical power for a public that, quite justifiably, wants to hear (or, more likely, stream) the best stories from all over the world.

To its credit, the Australian literary scene now pays considerably more attention to issues of race, gender and sexuality, in ways that render the valorisation of a “national identity” almost impossible. The problem doesn’t pertain merely to the traditional canon’s relationship with white Australia: even the most multicultural nationalism depends, by definition, on a boundary separating citizens and foreigners.

But the new preoccupation with social justice, while necessary, is not sufficient to re-ground a literary project.

Any understanding of culture solely in terms of politics faces the same dilemma encountered by the writers of the CPA. If we conceive of writing as a mere proxy for activism, we become bad activists (poetry makes nothing happen) and worse writers, devoid of any criteria for judging the aesthetic value of our work.

That’s why this history matters. For all its flaws, the nationalist paradigm provided a basis for Christesen and Murray-Smith to privilege literary achievement: the spiritual wellbeing of the country depended, they declared, on great writers. We can’t – and shouldn’t – revive their project. But we certainly should learn from it, as we strive for something better.