On your next visit to the park, try and count all the different species you can see. Away from the closely mown grass, you might spot wildflowers attended by pollinating insects, like bees, wasps and hoverflies. Overhead there are the gnarled branches of mature trees, some of which will have lived for hundreds of years, providing food and refuge for generations of fungi and insects.

You may find yourself immersed in the chorus of songbirds fervently competing for mates. There will undoubtedly be fleet-footed mammals scurrying in the bushes and amphibians hiding under logs.

But there’s also another world of wildlife floating all around you. This is the biodiversity that we can’t see with the naked eye – the secret life of the air we breathe.

Invisible nature

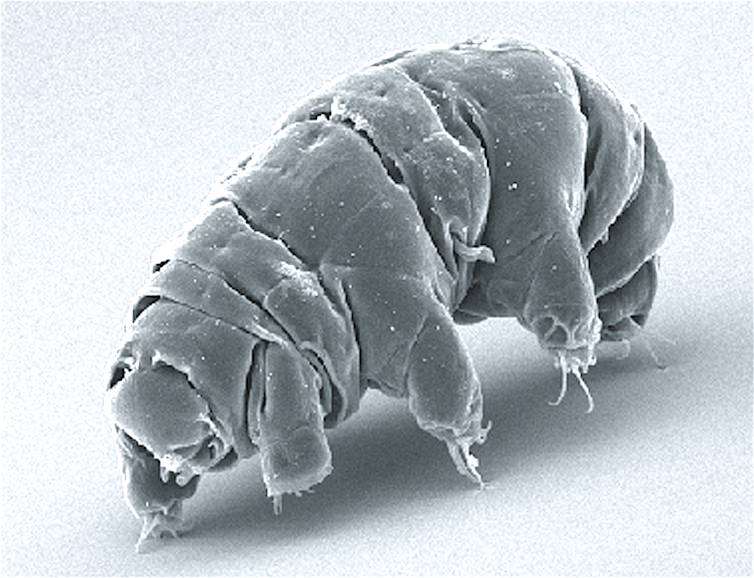

The air is full of microscopic life forms: dense clouds of bacteria, tiny fungi and algae which surround us. There are single-celled organisms called protozoans and vast quantities of viruses, moss spores and plant pollen. There may even be a few microscopic moss-dwelling animals called tardigrades, also known as water bears or moss piglets because of their mammal-like appearance (under the microscope, at least).

Humans are bombarded by all these tiny organisms on a daily basis. Studies have shown that up to a million microbial cells can be found in a single cubic metre of air, and people can inhale a whopping 100 million bacteria each day.

But where does all this invisible life come from? And what does our exposure to it mean for our health? Together with colleagues, we set out to discover the kinds of microbes people are likely to encounter during walks in urban parks.

Our recent study in Scientific Reports suggested that many of the life forms floating in the air actually originate in the soil beneath our feet. This makes a lot of sense. Soil is arguably the most biodiverse habitat on Earth, and a single gram of it can contain more microbes than there are humans on the planet.

Microbes are incredibly light, so they become airborne really easily and are carried far and wide on the wind. They can be lifted from the soil in air bubbles that form in raindrops and clump together on dust particles which fall from the atmosphere.

Our study showed that distinct layers of bacteria form in the air, with different species and quantities of microbes occurring at different heights. At the average head-height of a standing adult, there were fewer but also different kinds of bacteria compared with those in the air lower down at the head height of a child or sitting adult.

This means that we may be exposed to different kinds of microbes – some good for us, some bad – depending on our height and posture. Exposure to lots of different types of microbial life, particularly in childhood, is generally considered to be a good thing, because it allows our immune systems to build up a strong army of cells that protect us from pathogens. The greater number of microbial species we detected closer to the ground could be vital in ensuring children develop robust immunity later in life.

But it also matters which environments we spend time in. After collecting 135 samples, we found that the air in the wooded areas of an urban park near Adelaide in Australia contained more bacterial species but fewer potential human pathogens than nearby sports fields. Trees appear to filter the microbial communities in a given airspace, reducing the risk of exposure to microbes that cause disease. Because trees also seem to increase microbial diversity in the air, allowing more of them to grow in urban areas could provide an important health benefit by enhancing our immune systems.

This wouldn’t only benefit human health. Although we can’t see the microbes and the other members of the microscopic world around us, they’re fundamental to the proper functioning of ecosystems, plant health and communication (yes, plants talk to each other), and even climate regulation.

We still know relatively little about the unseen life in the air we breathe, but our preliminary findings reveal a few of their secrets. We would be wise to learn and encourage them in the important roles they play.