“We have a sense that we are about to face immense upheavals,” Maja Göpel writes, and we need to find ways to tackle multiple problems at once. The context for this statement is an account of a 2019 incident staged by Extinction Rebellion protesters in a London tube station.

Review: Rethinking our World – Maja Göpel (Scribe)

Two men carrying a banner proclaiming Business as Usual = Death climbed on the roof of a train in the morning rush hour, preventing its departure and disrupting all other services on the line. Frustrated commuters pelted them with sandwiches and drink bottles, then dragged them to the ground and laid into them until the police arrived.

For Göpel, it was a definitive clash of human objectives: one side wanted to save the planet, the other wanted to get to the office.

Read more: Extinction Rebellion protesters might be annoying. But they have a point

More specifically, one side called for a radical shift in thinking, while the other clung desperately to an ingrained set of priorities. The story serves as an arresting (literally) way to illustrate a now all-too-familiar cultural dilemma. If this book has something distinctive to offer amidst the plethora of volumes devoted to ecological crisis, it is as an attempt to focus on the problem of human cognition – or, to put it more plainly, collective mind-set.

Plain speaking is essential to Göpel’s role as a public communicator in a range of national and international forums including the World Future Council, the Club of Rome, and the German Advisory Council on Global Change, for which she served as secretary-general from 2017-20.

In Rethinking Our World she aims to bring to a wider audience some key points from The Great Mindshift, her book written for policy makers in 2016.

Her aim at that time was to respond to a 2011 flagship report from the German Advisory Council on Global Change that called for “a Great Transformation,” an allusion to the title of a 1944 work by Austro-Hungarian theorist Karl Polanyi, who argued that the development of the modern state was bound up with the development of market economies: there could be no change in one without a change in the other.

The report called for “a new kind of discourse” between government and citizens. Göpel thought more needed to be said about what that meant.

In revising her work for a wider audience, Göpel’s notion of the mindshift itself required some changes of orientation. A more loosely stated, more general principle becomes her concern in this book. “We have forgotten how to assess whether our ways of thinking are fit for purpose in our times,” she says.

Public consciousness shifts all the time, in much less defined and more unpredictable ways than is the case with established systems of thought. As a political economist, her concern is with how dominant paradigms in economic thinking turn into assumptions that are embedded in popular thinking, usually with the help of sustained political spin.

She dwells on how commitment to economic growth became an unquestionable imperative, accompanied by the presumption that it is acceptable to exhaust elements in an ecosystem because they can be replaced with artificial equivalents. Bees, for example, became the subject of an experiment in artificial pollination funded by the Walmart corporation. This she presents as a classic example of delusory thinking, based on failure to understand the complex interconnections of the natural world.

“If we follow the theory too slavishly,” she writes, “the eventual result will be the production of a new reality.”

‘Business as usual’

Göpel explains things well. She is lucid, succinct, and avoids strident polemic. And she enforces her argument with compelling narratives. Her account of the Extinction Rebellion protest on the London tube carriage, for example, has a tragic counterpoint in an event she personally witnessed at a demonstration against the 2003 WTO conference in Mexico.

Prominent on the agenda were the worsening consequences of globalised trade in agriculture. Just a few meters away from where she stood in the crowd of protesters, a farmer from South Korea climbed the security fence and stabbed himself in full view of the assembly.

Lee Kying-hae, who died in hospital soon after, had been “something of a guru of sustainable agriculture,” who taught natural livestock-farming methods to others on his model farm. But then came the new deregulations, and a massive supply of cheap beef from Australia. The repossession of his farm and his land was the final cruelty, and having seen this happened to many others, he travelled to Mexico to make his own final response.

“Business as Usual = Death” may have been a slogan to London tube travellers: to small farmers around the world, it is plain and immediate reality.

This sense of human urgency makes for a very readable book, but the problem is that most of her readers are likely to know much of what she is explaining. We are used to seeing statistics telling of eye-watering inequalities, such as those she cites in her chapter on “fairness,” drawing on a study of the emissions costs incurred by ten celebrities through air travel alone during 2017.

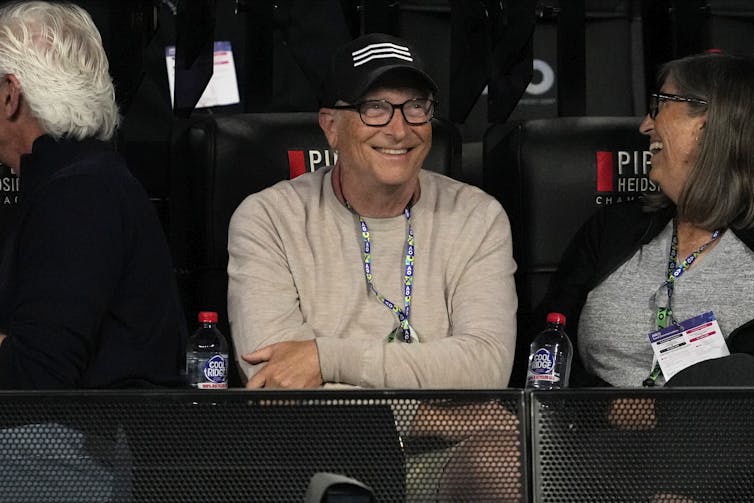

Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Jennifer Lopez and Oprah Winfrey were amongst the case studies. Gates came out on top, with a total of 350 flying hours through the year, most of them in a private jet, emitting an estimated total of 1600 tonnes of carbon dioxide.

Read more: Feeling flight shame? Try quitting air travel and catch a sail boat

Göpel sets this against the estimates published from the Paris climate conference of the reductions to 42 tonnes per capita in emissions that would be required to bring global warming down to 1.5 degrees, the scientific consensus for a viable target. On this modelling, Gates in a single year used the equivalent of 38 times the lifetime budget for the average world citizen.

Preaching to the converted

How can we continue to tolerate an economic system that produces a Bill Gates and a Lee Kying-hae? Clearly this is a devastating failure of human intelligence, but how can that be turned around? A useful instrument, Göpel suggests, is the “veil of ignorance” thought experiment proposed by philosopher John Rawls in the early 1970s.

Participants are invited to contemplate the prospect of a lifetime on the planet, like an unborn child, with no knowledge of where or in what circumstances they may come into the world. From this state of cognition (or incognition), they are then asked to describe what kind of society they would choose for their future.

It’s a more sophisticated version of the “cake trick” played with children: one cuts, the other chooses which half to take. What if this thought experiment were taught in every school? Given the growing political intervention in school curricula, even in liberal democracies, that’s unlikely to happen. So we are left with the question of how the great reset in human intelligence is to be pursued, and how, or whether, a book such as this is likely to help.

Data sets from the 2015 Paris Agreement are not new information. Neither are accounts of the forced production of chicken meat, or the statistics on clothing waste. More and more people question news reports of economic growth as a necessarily good thing, are aware that the correlation between growth and wellbeing is ill-founded, and that there is an inverse correlation between growth and climate change.

Read more: To make our wardrobes sustainable, we must cut how many new clothes we buy by 75%

In the seven years since The Great Mindshift was published, Extinction Rebellion have made a huge impact, as have so many other movements and campaigners – enough, at any rate, to move public awareness ahead of where this book assumes it to be.

Göpel does not advocate any particular economic policies or models. As a social scientist, she is concerned to identify patterns in collective thinking that drive human behaviour, but, astute as she is in her analysis, the looming question is: what will actually drive the change she calls for?

The critiques she offers have already been put forward in countless best-selling books, by Guy Standing, Mariana Mazzucato, Evan Osnos, Naomi Klein, Elinor Ostrom and many more. Of course, such writings themselves interact and build on each-other to form a kind of ecosphere, to which this book makes its own contribution, but when Göpel issues “an invitation to rescue our future” (her subtitle), to whom is this addressed?

Those likely to buy the book, however numerous, are unlikely to need the kinds of persuasion she is offering. Preaching to the converted can produce the illusion of cutting through, but it seems unlikely that this publication will do anything more.