As the Ebola outbreak continues in West Africa, hospitals and health systems are preparing for possible cases in Australia. What would this response look like?

Australia has a system of “designated hospitals” for Ebola. All patients with confirmed Ebola will be transferred for management at these specialised centres, based mostly in capital cities or regional centres with international airports.

For the other hospitals, preparedness focuses around identifying patients with possible Ebola infection and confirming (or more likely, excluding) this diagnosis.

Identifying patients with possible Ebola

Hospital emergency departments routinely ask for patients who have returned from overseas travel within the last month to identify themselves to staff. This is relevant for a number of contagious infections, including measles, avian influenza, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), as well as Ebola.

Patients with any symptoms of suspected infection who have recently travelled overseas are immediately placed in a single room to be further assessed.

For patients with suspected Ebola, four groups of hospital staff are activated: one team to look after the patient; one staff member or team to make sure staff in the emergency department are briefed; one physician to liaise with public health authorities and other relevant departments; and one group to oversee the hospital response. In smaller hospitals, some of these tasks may be performed by the same staff, and the roles may vary with the structure of individual hospitals.

Caring for patients with suspected Ebola

The main team that cares for the patient will initially make an assessment of how likely Ebola is as a diagnosis, how sick they are, and if, Ebola is being considered, how infectious they potentially are. In some patients, this assessment is simple – Ebola can be excluded if they have not travelled to the relevant countries in West Africa within 21 days (the maximum incubation period of Ebola).

A major consideration for this team is not to miss more likely diagnoses such as malaria or bacterial disease. In addition to antimalarials and antibiotics, patients may require fluids to correct dehydration, as with any infection.

We also recognise that patients with suspected Ebola are likely to be particularly frightened and anxious, and special efforts will need to be made by the treating team to address their concerns.

Infectiousness is directly related to the amount of body fluids – vomit, diarrhoea and blood – that the patient is excreting, and this has implications for the type of personal protective equipment that is required.

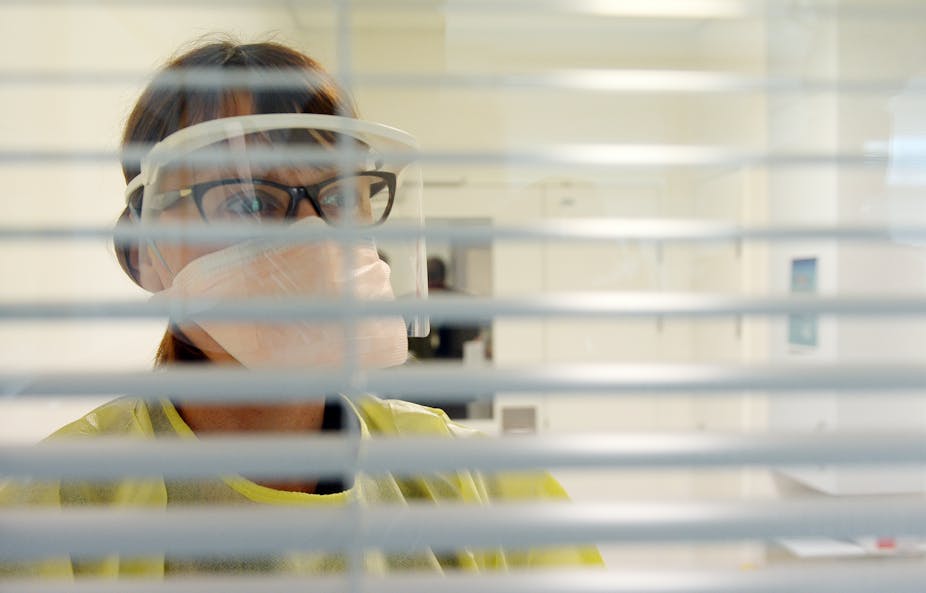

To protect themselves, staff will work in pairs – one as the primary nurse or doctor, and another staff member to make sure they use their personal protective equipment correctly. Our hospital, like many around the country, are currently conducting training sessions with staff in the emergency department to make sure they are familiar with the correct protocols.

For the highest-risk patients, there is some variation in the exact types of personal protective equipment that is used between hospitals. At our hospital, protective equipment for staff consists of boots and shoe covers, two pairs of gloves, a mask that covers the nose and mouth, goggles that cover the eyes, a hood that covers the head and neck, and a long-sleeved gown that is impermeable to fluids. The US Centers for Disease Control have recently revised their guidelines for personal protective equipment to match these standards.

The names of all staff entering the room will be logged so they can be followed up and counselled later.

Special cleaning teams are required to disinfect the room, and waste will need to be suitably disposed of. This will be co-ordinated by the hospital’s infection control unit, who are specialists in the use of personal protective equipment and disinfection.

Caring for staff, contacts and other patients

A second team consists of senior nurses and doctors in the emergency department, and they will be tasked with ensuring that the emergency department continues to operate. Emergency departments can be very busy places, and it is important that other patients in the department feel safe and also receive appropriate treatment.

The team will also ensure that the staff looking after the patient with suspected Ebola are experienced and trained, and that other health-care workers in the emergency department are kept up-to-date with developments.

A third team consists of infectious diseases physicians. They will provide advice to the treating team about the clinical management of the patient, and will notify the public health authorities.

Blood tests for Ebola are only performed at highly specialised laboratories in most states under strict isolation, and blood specimens need to be suitably packed for safe transport.

The results of testing will be relayed back to the treating team and the public health units. If positive, arrangements will be made to transport the patient safely to the designated hospital.

For patients who test positive for Ebola, there are also state and national plans for how to follow up people who are in contact with the patient, including household contacts, those who may have travelled on public transport with the patient, and health-care workers who have cared for the patient.

There are also current processes to provide information to all arrivals at airports, including plans for how to manage people who are unwell on arrival.

For returning health-care workers who have assisted in treatment centres in West Africa, there are guidelines for them to be checked for fever twice each day until the incubation period is over.

Working with the media and the public

Finally, the experience with other suspected cases reminds us of the intense interest from the public and media.

A senior member of the hospital executive will be tasked with communicating any important developments to hospital staff, while respecting the patient’s right to privacy. They will develop a plan to communicate to the media and the public, and ensure that the remainder of the hospital continues to function.

There has never been a case of viral haemorrhagic fever such as Ebola in Australia, so our plans are yet to be properly tested. But because travellers to West Africa have a high incidence of malaria and other diseases that may resemble Ebola, this protocol to identify, diagnose and safely manage patients with suspected disease is likely to be activated regularly over the coming months.

Staff at most hospitals are on high alert for patients with possible Ebola, and to date, a small number have already required testing to exclude this important infection.

All of us who work in developed countries such as Australia are acutely aware that the resources available to us are far more than is available in the affected countries. We are also conscious that our fates are linked – the likelihood of cases presenting in Australia is currently low, but may increase if the outbreak continues to spread to other countries in the region or elsewhere in the world.