The distinctive outline of Lindisfarne Castle perched on top of a rugged crag of basalt is one of the best-recognised images of north-east England and is a potent reminder of the important part the island played in the early history of Northumbria. This tidal island – only accessible at certain times of the day – lies close to the modern border between England and Scotland. Standing on its south-east corner was once one of the most important centres of Christianity in early medieval Britain.

As part of an exciting new project, Durham University and DigVentures, an innovative archaeological social enterprise, are planning a new investigation of this important site to find out more about this mysterious early monastery.

We know little about the prehistory of the island, although the flint tools of Mesolithic hunters and gatherers have been found close to its rocky northern shoreline. It’s only in the seventh century AD that it suddenly emerges into historic view.

Medieval kingdoms

The early years of the seventh century had been tumultuous for the rapidly expanding kingdom of Northumbria. Under King Aethelfrith, the kingdom had been forged from two competing dynasties, and under King Edwin, the Northumbrian rulers began to adopt Christianity, having been converted from the worship of their pagan gods by missionaries from Kent. In the inevitable inter-dynastic scuffles typical of early medieval kingdoms, Edwin’s rival and successor Oswald had been exiled to Scotland, where he too converted.

Crucially though, Oswald adopted a different strand of Christianity from the monks of the Scottish isle of Iona, where it is thought he first encountered the church. When he arrived back in the heartlands of Northumbria he wanted to make a religious statement that set him apart from Edwin and his legacy. Working with monks from Iona, he established a new monastery on Holy Island.

This was not some remote island fastness, where ascetic monks could escape to confront god in the wilderness. Instead, it straddled major sea and land routes and was just across the water from the great Northumbrian palace at Bamburgh. The monastery rapidly achieved prominence, helped by its royal patrons.

Miraculously, the monastery survived the fall-out of the Synod of Whitby in 664, when the Scottish-influenced Christianity brought to the north by Oswald gave way to the pushy Roman and Kentish traditions initially promoted by Edwin.

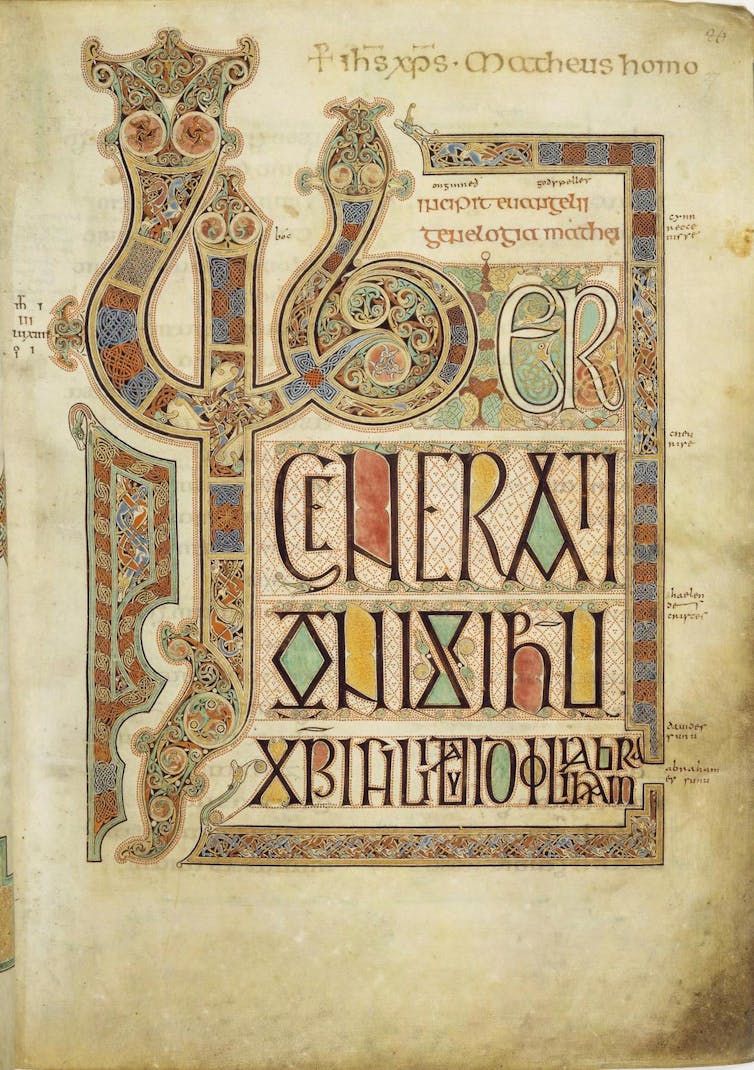

In the following years, Lindisfarne achieved a new prominence under its abbot, Cuthbert, a monk torn between his desire for the life of a hermit and the demands of high religious office. Soon after his death he was created a saint and his cult was promoted by the monks on the island. The creation of the great illuminated manuscript known as the Lindisfarne Gospels, one of the great monuments of Western art, was probably part of the campaign to promote Cuthbert carried out by the religious community.

Ousted by Vikings

The monastery became increasingly wealthy, but in the late eighth century suffered one of the first Viking raids on Britain. The tempo of these attacks increased and according to the monastic historians, the monks left the island in 875. After a century-long exile, they set up a new home in Durham.

Yet, despite the high profile of the monastery in Northumbrian history, remarkably little is known about the monastery itself, beyond passing observations in the works of Bede and other early writers. A fine collection of Anglo-Saxon sculpture has survived, but little is known about precisely where it was found. The ruins of a later Norman priory now dominate the village, and may stand over part of the earlier monastery. Early medieval monastic centres were large, dispersed and sprawling settlements, and it is likely that Cuthbert’s monastery may have extended beyond much of the area covered by the modern village.

In recent years archaeologists are starting to get a better understanding of the archaeology of the island. Looking at the finds discovered – but never analysed – by Victorian gentleman archaeologists who crudely cleared out the later priory, a number of Anglo-Saxon objects have been recognised. These have been supplemented by the occasional appearance of similar items in small-scale archaeological investigations that have taken place in advance of construction.

A major new geophysical survey around the village has also been carried out. This has identified a number of areas where possible traces of the monastery have been identified, although of course, until we excavate, we won’t know for sure.

Play a part

This project is one of the first archaeological projects to use crowdfunding. The project has been launched on the DigVentures website, allowing anyone interested in discovering the past to pledge support. In return for backing the project, supporters become part of the dig team.

By using DigVenture’s crowdfunding and crowdsourcing model, we are hoping to get people who subscribe into the field, where they will be using an entirely paperless recording system. By using a bespoke app, every object and discovery will be logged live from the trenches via iPads, tablets and smartphones, making it instantly accessible from anywhere in the world. As the site is recorded, all the data will be uploaded online, allowing subscribers to follow the progress of the excavation as it happens. It will also give the excavation team a chance to solicit information and advice from the international research community. These new approaches set to provide archaeologists with a model for carrying out fieldwork.

The centrality of the first Lindisfarne monastery in the history of the Anglo-Saxon Britain and its – until now – elusive nature gives this dig the potential to be one of the most important archaeological sites in the UK to be worked in recent years. This collaborative and open process of research and scientific excavation is the future of discovering the past.