In this series we pay tribute to the art we wish could visit — and hope to see once travel restrictions are lifted.

Have you ever entered a gallery, cathedral or grand old ballroom and drawn breath with surprise? Usually, it is opulence, vastness or one stunning painting or sculpture that evokes this response — think Michelangelo’s David, or Chartres Cathedral or the hall of mirrors at Versailles.

In London, an extraordinary gallery draws gasps because there is none like it anywhere else. It is like entering a giant “globe” covered in paintings of faraway places and plants. You can walk from South America to North America to Asia in a few paces.

All the paintings are by the Victorian-era female botanical artist and explorer Marianne North. The small gallery nestles in a stunning natural setting — Kew Gardens beside the Thames River.

Read more: If I could go anywhere: Marie Antoinette's private boudoir and mechanical mirror room at Versailles

A very intrepid painter

The design of the gallery and the layout of the 800-plus paintings were largely North’s idea, assisted by Kew Gardens staff. Though she was a largely self-taught botanical illustrator, she also discovered four specimens that were named in her honour.

I remember my first impression of the peacefulness and softness on entering the gallery, elicited by a timber-panelled gallery covered top-to-bottom with paintings. It is a tightly packed mosaic of artworks.

Then I notice the gold lettering of countries and continents above the panels —America, Australia, Japan, Jamaica — and begin to explore the natural world as it was in Victorian times.

The vibrancy, colour and beauty in each individual painting emerges on closer viewing.

I walk from one continent to another noticing the unique vegetation of each, but also the similarity and diversity of natural forms — when these paintings were being created and collated, Charles Darwin had already written:

[…] endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

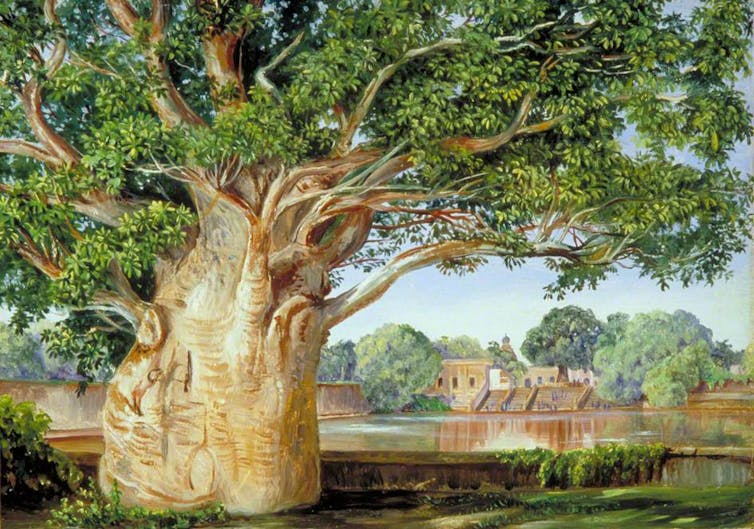

The gallery displays this exquisitely, from a grand avenue of Indian rubber trees in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), medicinal plants from the tropics, vivid tangerine flowers on coral trees in Brazil, early coffee plantations in Jamaica, to a tall and majestic monkey puzzle tree in Chile. Australian banksia, bottle tree and bottle-brush are accurately and beautifully depicted.

Within the walls of the gallery, I can even travel back in time to see what Mudgee in NSW looked like in the late 1800s.

Read more: Friday essay: the forgotten German botanist who took 200,000 Australian plants to Europe

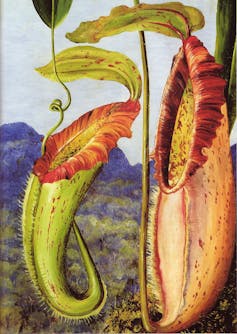

Then there are the four specimens named in North’s honour. Kniphofia northiae, discovered in South Africa, now grows in many gardens with the common name red hot poker (Painting no. 367). Northia seychellana is also called the capucin tree Painting no. 501). Nepenthes northiana, a large and unusual pitcher plant, was discovered by Marianne in Borneo (Painting no. 561). And crinum northianum , in the lily family (Painting no. 602), comes from Sarawak, Borneo.

When Charles met Marianne

North was one of several Victorian-era British female explorers. She was born (1830) into a wealthy family and had early connections to Kew gardens since her father knew its first director, Sir William Hooker.

Her interest in botanical art grew as an educational activity and as a means of passing on knowledge in pre-photography times. She made nearly 900 works from across the continents and larger islands.

North set out on her first main botanical tours in the 1870s, 40 years after Darwin sailed on HMS Beagle, determined to “paint from nature”. Her paintings of vegetation, birds, mammals and terrain, depicted with close accuracy, helped to foster awareness of the evolutionary connections between plants, animals and environment.

North and Darwin were in fact acquainted. In 1880 they met and discussed her paintings and he advised her to see and paint the Australian vegetation “which was unlike that of any other country”. North took Darwin’s advice, and returned to Down house in 1881 with a new collection spanning Townsville to Perth.

The world through her eyes

North gifted her botanical collection to Kew Gardens along with a gallery to house it. She arranged the paintings and also the decorations surrounding the doors to the gallery. Hence the unique design and global feel of the gallery interior. It opened in 1882.

Some 140 years later, we can explore her adventurous life and travels and view a global nature study in one gallery. With today’s technology we can see much of it online, which is handy during lockdown. I wonder what human expansion and global warming have done to those special places? If I could retrace North’s steps, what would I see?

After “browsing the continents”, you can exit the gallery into Kew Gardens. Among the 50,000 plants at the World Heritage site, you can search for the rare Australian Wollemi Pine, growing quite vigorously in the grounds.

The words of Darwin in 1859’s Origin of Species come to mind: “There is grandeur in this view of life”.

Read more: Janet Laurence: After Nature sounds an exquisite warning bell for extinction