It is unfashionable, or just embarrassing, to suggest the taken-for-granted late-modern economic order – neoliberal capitalism – may be in a terminal decline. At least that’s the case in what former Australian prime minister Tony Abbott likes to call the “Anglosphere”.

What was once known as the Chicago school of economics – the neoclassical celebration of the “free market” and “small government” – still closes the minds of economic policymakers in the US and its satellite economies (although perhaps less so in contemporary Canada).

But, in Europe, there has always been a deep distrust of the Anglo-American celebration of “possessive individualism” and its repudiation of community and society. Remember Margaret Thatcher’s contempt for the idea of “society”?

So, it is unsurprising that neoliberalism’s advocates dismiss recent European analyses of local, regional and global economies as the nostalgia of “old Europe”, even as neoliberalism’s failures stack up unrelentingly.

The consequences of these failures are largely unseen or avoided by policymakers in the US and their camp followers in the UK and Australia. They are in denial of the fact that not only has neoliberalism failed to meet its claimed goals, but it has worked devastatingly to undermine the very foundations of late-modern capitalism.

The result is that the whole shambolic structure is tottering on the edge of an economic abyss.

What the consequences might be

Two outstanding European scholars who are well aware of the consequences of the neoliberal catastrophe are French economist Thomas Piketty and German economist Wolfgang Streeck.

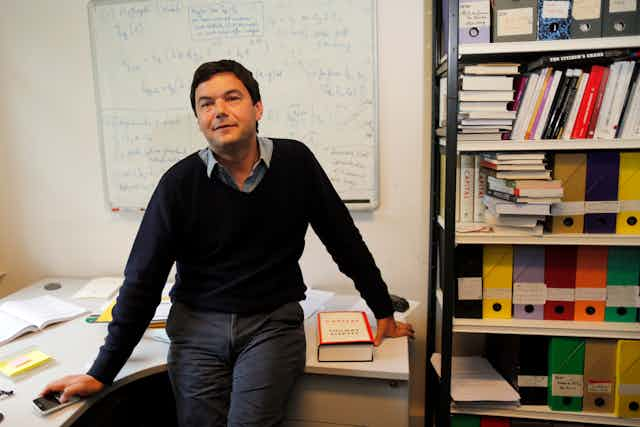

Piketty’s 2013 book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, charts the dangers of socioeconomic inequality in capitalism’s history. He demonstrates how this inequality can be – and has been over time – fundamentally destructive of sustained economic growth.

Most compellingly, Piketty documented in meticulous detail how contemporary neoliberal policies have constructed the worst forms of socioeconomic inequalities in history. His analysis has been underlined by the recent Oxfam report that showed a mere eight multi-billionaires own the equivalent amount of capital of half of the global population.

Despite Piketty’s scrupulous scholarship, Western neoliberal economies continue merrily down the road to nowhere. The foundations of that road were laid by the egregiously ideological policies of Thatcher and Ronald Reagan – and slavishly followed by Australian politicians on all sides ever since.

Streeck’s equally detailed scholarship has demonstrated how destructive of capitalism itself neoliberal policymaking has been. His latest book, How Will Capitalism End?, demonstrates how this neoliberal capitalism triumphed over its opponents (especially communism) by devouring its critics and opponents, obviating all possible alternatives to its predatory ways.

If Streeck is correct, then we need to anticipate what a post-capitalist world may look like. He thinks it will be terrible. He fears the emergence of a neocorporatist state and close crony-like collaboration between big capital, union leaders, government and the military as the consequence of the next major global financial crisis.

Jobs will disappear, Streeck believes. Capital will be intensely concentrated in very few hands. The privileged rich will retreat into security enclaves dripping with every luxury imaginable.

Meanwhile, the masses will be cast adrift in a polluted and miserable world where life – as Hobbes put it – will be solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.

What comes next is up to us

The extraordinary thing is how little is known or understood of the work of thinkers like Piketty and Streeck in Australia today.

There have been very fine local scholars, precursors of the Europeans, who have warned about the hollow promises of “economic rationalism” in Australia.

But, like the Europeans, their wisdom has been sidelined, even as inequality has been deepening exponentially and its populist consequences have begun to poison our politics, tearing down the last shreds of our ramshackle democracy.

The time is ripe for some creative imagining of a new post-neoliberal world that will repair neoliberalism’s vast and catastrophic failures while laying the groundwork for an Australia that can play a leading role in the making of a cosmopolitan and co-operative world.

Three immediate steps can be taken to start on this great journey.

First, we need to see the revival of what American scholar Richard Falk called “globalisation from below”. This is the enlivening of international civil society to balance the power of the self-serving elites (multinational managers and their political and military puppets) now in power.

Second, we need to come up with new forms of democratic governance that reject the fiction that the current politics of representative government constitute the highest form of democracy. There is nothing about representative government that is democratic. All it amounts to is what Vilfredo Pareto described as “the circulation of elites” who have become remote from – and haughtily contemptuous of – the people they rule.

Third, we need to see states intervening comprehensively in the so-called “free market”. Apart from re-regulating economic activity, this means positioning public enterprises in strategic parts of the economy, to compete with the private sector, not on their terms but exclusively in the interests of all citizens.

As Piketty and Streeck are pointing out to us, the post-neoliberal era has started to self-destruct. Either a post-capitalist, grimly neo-fascist world awaits us, or one shaped by a new and highly creative version of communitarian democracy. It’s time for some great imagining.

This article is based on an earlier piece published in John Menadue’s blog Pearls and Irritations.