On my first day as curator of the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, Pat Larter and Lola Ryan’s artworks were shown to me in order to demonstrate the idiosyncrasies of the once-private collection. But what does it mean to describe artworks as “idiosyncratic”, especially if those artworks share a number of very striking similarities?

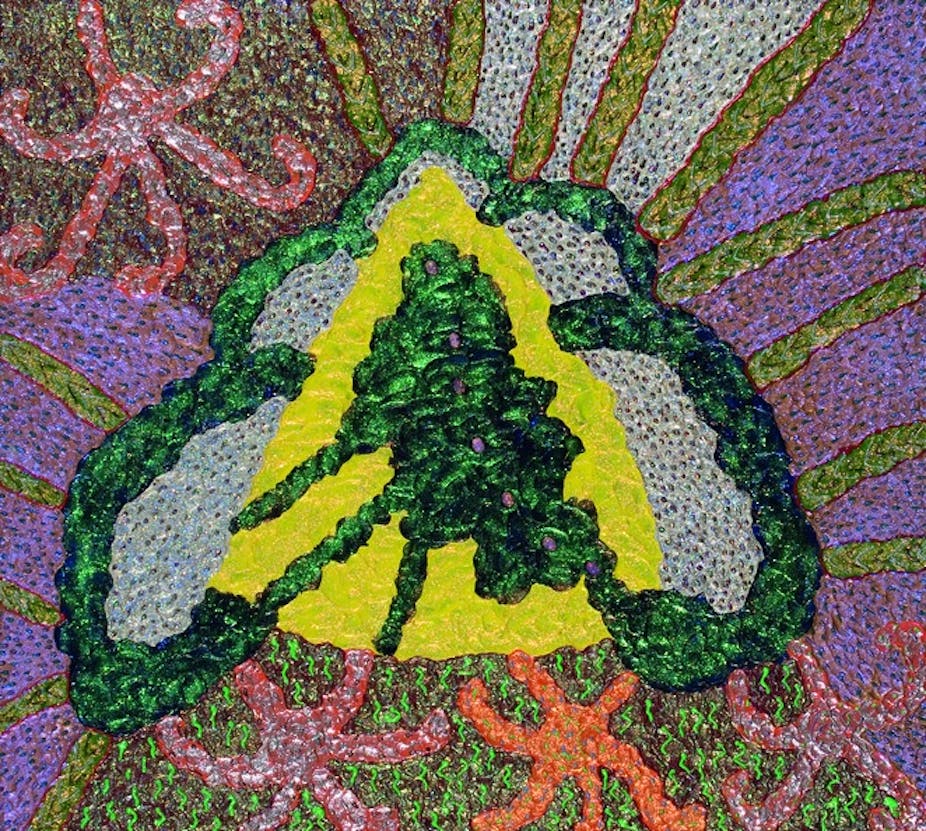

The works of both artists are on display in an exhibition titled Glitter at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery in Perth. The formal similarities between Larter’s paintings and Ryan’s objects are obvious immediately. They share a neon colour palette, the use of decorative pattern and the liberal use of glitter. Both are also, in their own way, part of a dialogue about “women’s work”.

Different histories, similar responses

Pat Larter migrated to Australia from England in the 1960s with her husband, the celebrated, recently deceased artist Richard Larter.

Her own art aimed to parody what she described as “malegiven sexual stereotypes”, largely focusing on the ephemeral forms of performance and mail art. Like her ephemeral works, Larter’s paintings and embellished “super-scans” can also be read as gleeful yet critical parodies of masculine tropes of representation and abstraction.

Lola Ryan’s shellwork boxes, Sydney Harbour Bridges and wall hangings continue a tradition particular to the Indigenous women of La Perouse. The Sydney suburb is the site of one of the first missions to segregate Australia’s First Peoples from white settlement. Missionaries introduced shellwork to La Perouse in the late 1880s – with the practice growing into both an important source of income and a local tradition unto itself.

That both artists have come to their sensibilities via very different contexts makes the similarities between them more striking. What is also striking is the “narrative” of response to these works. Both – generally in the case of shellwork and more specifically in the case of the Larters – have been overlooked by collecting institutions in favour of the men around them. Both artists’ works are frequently described as idiosyncratic, kitsch or, less kindly, tacky.

Kitsch, class and gender

Factors specific to each artist have contributed to their position “outside” mainstream art history.

For example, as shellwork is a “post-contact” tradition, museums and galleries interested in Indigenous culture initially looked to more “authentic” representations, such as wood carving or ochres. Pat Larter’s mail art was made to explore transgressive and political ideas, ephemeral gestures passed directly between artist and audience. Her foray into painting was brief, interrupted by her death in 1996.

However, Larter and Ryan’s shared aesthetic suggests that material hierarchies of taste, and relationships between “good taste”, gender and class, also bear consideration when considering the responses to them.

Pat Larter is most frequently described as her husband’s muse – although their artistic relationship is more complexly collaborative. Richard’s paintings of his wife were infamously provocative, but they maintain material traditions, translating photographs and pop ephemera into paint.

In contrast, Pat Larter’s figurative “super-scans” use early digital printing and materials with associations that are more hobby-craft – that is, more feminine - than high art. The super-scans have met frequently with critical disdain, having been described as “tawdry home-made porn”, despite comparing in intent and composition with their acrylic-on-canvas counterparts.

The great conundrum of La Perouse shellwork is that while it is simultaneously “not to everyone’s taste” it also has great popular appeal. The key motif of the Sydney Harbour Bridge stems from the trade of the objects as souvenirs on the beaches of La Perouse. The women sold their work to day-trippers from the nearby colony – and its popularity in this context is likely to have contributed to the survival of the practice.

It’s only in the last decade that shellwork has made its way into the category of “art”. It’s this transition that tends to cause problems. As a souvenir, shellwork perhaps represents tastes of the buyer rather than the maker. As a cultural object, it represents knowledge passed between generations and the adaptation and survival of a culture despite adversity.

Aesthetically, though, shellwork bears all of the hallmarks of what would be described in the world of “high art” as kitsch. Lola Ryan’s shellwork in particular tends towards the more flamboyant end of this spectrum. It is gaudy, encrusted, veneered, domestically scaled.

If kitsch means a cheaper, poorly produced pantomime of something authentic, then Lola Ryan’s works are definitely not kitsch – and neither are Pat Larter’s. In both cases, the choice of materials is deliberate. Neither are they lacking in the critical distance that kitsch suggests. Each supports complex analysis and long looking. Placed in the context of their relationship with tradition and with history, neither is that idiosyncratic.

Taste is cultural, and like objects can be read as such. Taste changes – but it also plays an important role in what we preserve, who we celebrate and who we remember. Both Pat Larter and Lola Ryan appear to be in the midst of a “moment” - a renewal of interest in their work. This moment is a useful one to bring the persistent hierarchies of good taste and high art into the light.

Glitter: Pat Larter vs Lola Ryan is on display at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery in Perth until September 27.