Chances are that when you hear the words “medieval magic”, the image of a witch will spring to mind: wizened old crones huddled over a cauldron containing unspeakable ingredients such as eye of newt. Or you might think of people brutally prosecuted by overzealous priests. But this picture is inaccurate.

To begin with, fear of witchcraft – selling one’s soul to demons to inflict harm on others – was more of an early modern phenomenon than a medieval one, only beginning to take hold in Europe at the tail end of the 15th century. This vision also clouds from view the other magical practices in pre-modern England.

Magic is a universal phenomenon. Every society in every age has carried some system of belief and in every society there have been those who claim the ability to harness or manipulate the supernatural powers behind it. Even today, magic subtly pervades our lives – some of us have charms we wear to exams or interviews and others nod at lone magpies to ward off bad luck. Iceland has a government-recognised elf-whisperer, who claims the ability to see, speak to, and negotiate with the supernatural creatures still believed to live in Iceland’s landscape.

While today we might write this off as an overactive imagination or the stuff of fantasy, in the medieval period magic was widely accepted to be very real. A spell or charm could change a person’s life: sometimes for the worse, as with curses – but equally, if not more often, for the better.

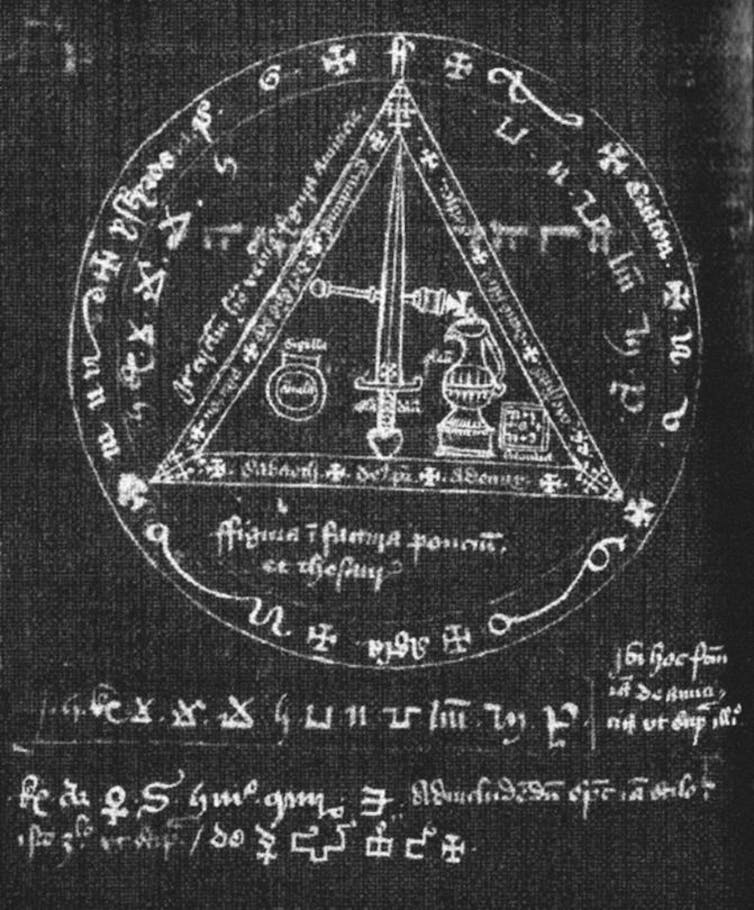

Magic was understood to be capable of doing a range of things, from the marvellous to the surprisingly mundane. At the mundane end, magic spells were in many ways little more than a tool. They were used to find lost objects, inspire love, predict the future, heal illnesses and discover buried treasure. In this way, magic provided solutions to everyday problems, especially problems that could not be solved through other means.

Crime of conjuring

This all may sound far-fetched: magic was against the law – and surely most people would neither tolerate nor believe in it? The answer is no on both counts. Magic did not become a secular crime until the Act against Witchcraft and Conjurations in 1542. Before then it was only counted as a moral misdemeanour and was policed by the church. And, unless magic was used to cause harm – for example, attempted murder (see below) – the church was not especially concerned. Often it was simply treated as a form of superstition. As the church did not have the authority to mete out corporal punishments, magic was normally punished by fines or, in extreme cases, public penance and a stint in the pillory.

This might sound totalitarian today, but these punishments were far lighter than those wielded by secular courts, where maiming and execution were an option even for minor crimes. Magic, then, was placed low on the list of priorities for law enforcers, meaning that it could be practised relatively freely – if with a degree of caution.

Among the hundreds of cases of magic use preserved in England’s ecclesiastical court records, there are a number of testimonials claiming that the spells were effective. In 1375, the magician John Chestre boasted that he had recovered £15 for a man from “Garlickhithe” (an unknown location – possibly a street in outer London).

Meanwhile Agnes Hancock claimed she could heal people by blessing their clothes or, if her patient was a child, consulting with fairies (she does not explain why fairies would be more inclined to help children). Though the courts disapproved – she was ordered to stop her spells or risk being charged with heresy, which was a capital offence – Agnes’ testimony shows that her patients were normally satisfied. As far as we know, she did not appear before the courts again.

Magic by royal patent

Young and old, rich and poor alike used magic. Far from being the preserve of the lower classes, it was commissioned by some very powerful people: sometimes even by the royal family. In a defamation case from 1390, Duke Edmund de Langley – the son of Edward III and uncle to Richard II – is recorded as having paid a magician to help him locate some stolen silver dishes.

Meanwhile, Alice Perrers – mistress to Edward III in the late 14th century – was widely rumoured to have employed a friar to cast love spells on the king. Though Alice was a divisive character, the use of love magic – like using it to find stolen goods – was probably not surprising. Eleanor Cobham, duchess of Gloucester, also famously employed a cunning woman to perform love magic in 1440-41, in this case, to help conceive a child. Eleanor’s use of magic got out of hand, however, when she was accused of also using it to plot Henry VI’s death.

In many ways magic was just a part of everyday life: perhaps not something that one would openly admit to using – after all, it was officially seen as immoral – but still treated as something of an open secret. A bit like drug use today, magic was common enough for people to know where to find it, and its use was silently recognised despite being frowned upon.

As for the people who sold magic – often termed as “cunning folk”, though I prefer “service magicians” – they treated their knowledge and skill as a commodity. They knew its value, understood their clients’ expectations and inhabited a marginal space between being tolerated out of necessity and shunned for what they sold.

As the medieval period faded into the early modern, belief in diabolical witchcraft grew and a stronger line was taken against magic – both by the courts and in contemporary culture. Its use remained widespread, though, and still survives in society today.