Why would a country with a third of its population living in poverty support a global agreement at the Paris climate talks? With per capita greenhouse emissions of about a tenth of many developing countries, why wouldn’t India just argue that it should be exempt from climate deals while it focuses on bringing electricity, food and jobs to its hundreds of millions of poor?

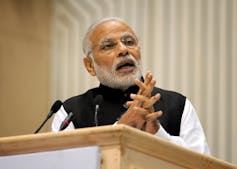

In short, because a strong global agreement on climate change is in India’s interests and the political interests of its Prime Minister Narendra Modi, as well as those of the international community.

As the world’s fourth-largest greenhouse emitter overall, India’s actions matter hugely to future global emissions, and to the prospects of a successful deal in Paris.

But fortunately, India’s vision and desire to develop sustainably makes it more likely, not less, that it will join the prospective Paris agreement – assuming that it gets the financial help it needs from the international community.

Rapid transition

Rather than set an overall emissions target, India has committed in its formal UN climate pledge to reduce the emissions intensity of its economy by 33–35% by 2030 from 2005 levels, and to source 40% of electricity from non-fossil sources by the same date.

Under Modi’s prime ministership, the country is undergoing a rapid transition towards a low-pollution and climate-resilient future. This move is evident in its electricity, agricultural, and cities and urban transport sectors.

In June, Modi’s government approved a five-fold increase in India’s solar electricity target – up from 20 gigawatts to 100 GW by 2022. This is an ambitious target and achieving it would see India surpass Germany as the world leader in solar. Modi foretold of a shift in India’s electricity mix while on the election campaign trail last year, hailing a “saffron revolution” that would embrace non-fossil energy.

Warming to the revolution theme, June also saw Modi call for a “second agriculture revolution” to ensure that India is prepared for increasingly erratic climatic conditions, including more frequent droughts, heatwaves, and unseasonal storms. He urged farmers to become “more scientific” in their approach, saying:

Farmers practising traditional farming believe that unless their field is filled with water they cannot get good crops, but this may not be scientifically true because drip irrigation [and] irrigation through sprinklers are more effective and reduces [use] of water and nutrients.

In May last year, Modi announced his vision to renovate 500 Indian cities and build 100 completely new “smart cities” from scratch, as part of a move towards what the government calls “clean and sustainable” urban spaces. “Cities in the past were built on riverbanks,” Modi said, “but in the future, they will be built based on availability of optic fibre networks and next-generation infrastructure.”

Cost and opportunity

Together, these plans for India’s, electricity, agriculture and cities can deliver a variety of social, economic and environmental benefits – not least for the 300 million Indians living without access to electricity. And these plans will deliver a range of different benefits all at the same time.

Take, for instance, the idea of installing a cheap, off-grid solar panels in villages that are not on the electricity network. Besides supplying power, this will also create low-skilled (installation) and high-skilled (engineering) employment opportunities for India’s massive youth population (the largest in the world); can potentially avert many thousands of premature deaths from acute respiratory infections caused by smoke inhalation from indoor cooking and heating with biomass; and will avoid adding significantly to greenhouse emissions in the process.

But, as one would expect, this transition will be expensive. India’s UN climate pledge estimates that more than US$2.5 trillion (at 2014-15 prices) will be required to meet India’s climate change and development plans between now and 2030. While the Indian government has allocated billions for these projects, and foreign investment has been forthcoming from major industrial economies such as the United States and Europe, much more foreign investment is needed for India to reach its climate goals.

Yet there is much to gain from India’s push for a low-carbon future – and not just for India. The transition forms a key part of Modi’s vision for a “modern” India, or as he describes it: to “refine, rebuild and transform the national character”. For Modi, India must no longer be known as a country that is “poor”, “old”, “unhealthy”, “unskilled”, “filthy”, and “underdeveloped”.

Crucially, Modi’s vision fits almost exactly with the United Nations’ desire for climate action. As UN climate negotiator Christiana Figueres explained in her opening address at last year’s Lima climate talks:

The time has come to leave incremental change behind and to courageously steer the world toward a profound and fundamental transformation. Ambitious decisions, leading to ambitious actions on climate change, will transform growth – opening opportunity instead of propagating poverty.

This creates the situation where identities, and therefore interests, align. Modi needs international support from industrialised countries to fulfil his dream of a modern India. At the same time, the UN – along with key advocates of climate action such as Europe and now the United States – need India to modernise cleanly to avoid dangerous global warming.

This overlap in identities and interests is positive news for advocates of a strong global agreement to be reached in Paris in December this year, and its successful and ongoing implementation thereafter.

This article is based on a briefing paper published by the Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, which is also publishing a blog on all the developments from the COP21 climate summit.