The increasing level of Indonesia’s government debt has become a hot topic ahead of the 2019 presidential election. The central government debt has increased by about 48% since President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo came to office in 2014, or almost double that of the previous administration.

The opposition leader, Prabowo Subianto, who will once again challenge Jokowi in the upcoming election, claimed that this rising debt would likely bankrupt Indonesia by 2030. In response, Jokowi said that Prabowo’s statement was overly pessimistic.

This article offers an objective elaboration and analysis of the government debt situation in Indonesia to help answer the public’s concern on the prospects of the country’s economy.

Increased appetite for borrowing

Uncontrollable government debts plunged Greece into crisis in 2017. The Greek experience was a wake-up call for countries to carefully evaluate their strategies for managing their debt. Prabowo’s statement seemingly reflects his fear that Indonesia might follow in Greece’s footsteps.

But will Indonesia end up like Greece?

Let us first examine the current status of Indonesia’s government debt.

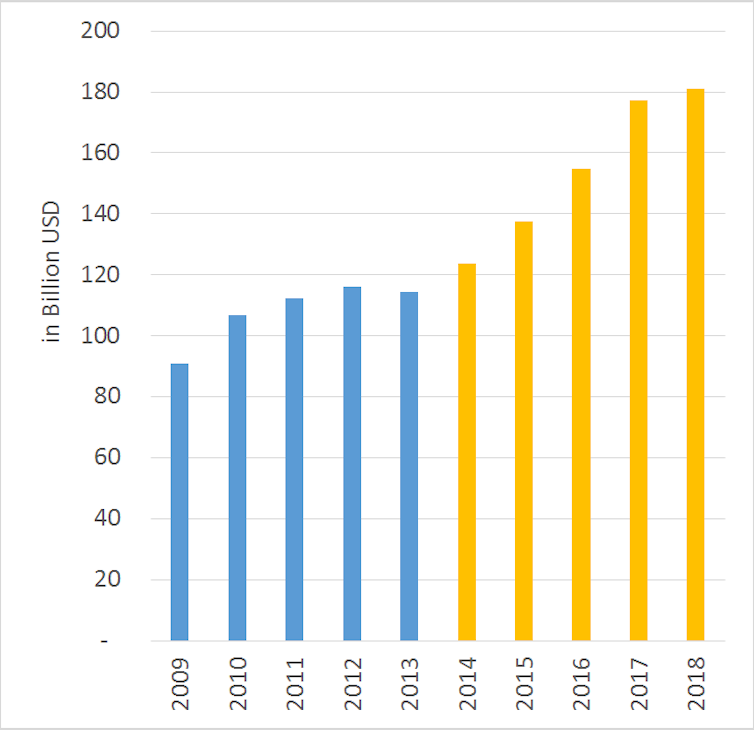

When Jokowi came into office in 2014, his administration inherited a debt of US$122 billion from his predecessor, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY). Four years later, this debt has risen by 48% to US$181 billion. The increase is quite substantial as under SBY’s five-year administration, from 2009 to 2013, the debt increased by 26%.

Meanwhile, the country’s ratio of debt to gross domestic product (GDP) increased from 24.7% to 30% between 2014 and 2018. This level is, however, lower than the 60% limit imposed by the country’s debt management constitution.

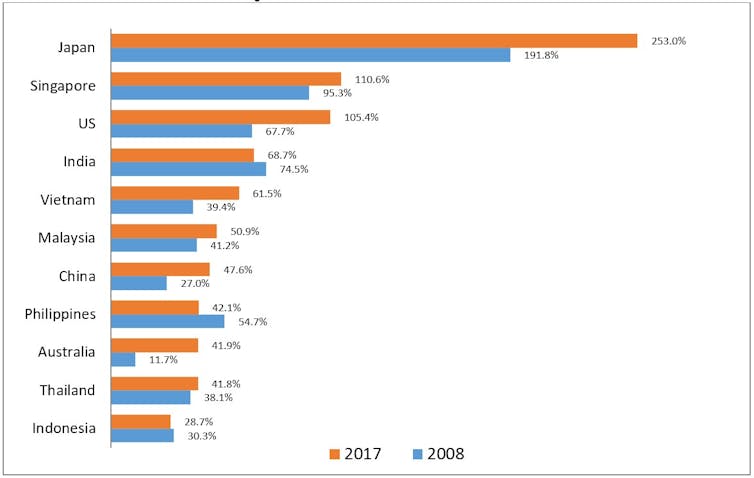

Compared to other countries, Indonesia’s debt-to-GDP ratio is still manageable. The debt-to-GDP ratios of the US and Japan, for example, stand at a staggering 105% and 253%, respectively, as developed countries can easily borrow funds to help finance their deficits. Within the Southeast Asian region, Indonesia’s debt-to-GDP ratio is also comparatively low.

A further analysis of Indonesia’s debt

Once we understand the current status of Indonesia’s debt, the next question is: should we be too concerned about it?

Let us now analyse Indonesia’s strategies in sourcing its debt.

In recent years, Indonesia has become more dependent on local lenders than foreign ones in efforts to mitigate exchange-rate risk and reduce vulnerability to global shocks associated with external debt. This strategy has been reflected in the increasing use of rupiah-denominated debt securities issued to the Indonesian public.

The latest statistic from Bank Indonesia showed that the share of foreign loans in Indonesia’s debt portfolio decreased from 78% to 30% between 2008 and 2017. The share of rupiah-denominated debt securities rose from 21.7% to 70% during the same period.

Another key relevant issue is what Indonesia does with its debt.

By reducing the proportion of its external borrowings, Indonesia has more flexibility in spending its debt. Debt raised from foreign creditors often comes with conditions and boundaries on how the debtor can use the loans.

The government has allocated much of its debt money to developing infrastructure – a key priority of Jokowi’s administration. Massive spending has been channelled to large-scale projects, including airports, seaports, mass rapid transport system, toll roads, as well as thermal and hydro-power plants.

Under Jokowi’s budget plan, spending on infrastructure has consistently increased by nearly US$10 billion per year, almost four times that of the previous administration.

Jokowi has also prioritised spending in two other key sectors of the economy: education and health.

As mandated by the Constitution, and continuing the legacy of the SBY’s administration, the government has allocated 20% of the annual budget for education. One innovative education program of Jokowi will soon see an establishment of a sovereign wealth fund to finance scholarships for postgraduate education.

The government has also boosted spending to improve the country’s healthcare system. As of September 2017, around 70% of the Indonesian population enjoyed the benefits of the government-supported health coverage program. By 2019, the government aims to cover all Indonesians in the healthcare program.

In contrast to the above, Jokowi’s administration has cut the country’s fuel subsidy since 2015. Some considered this policy unpopular as it may adversely affect growth in the short run. Higher fuel costs can lead to an increase in production costs and a decrease in economic activity. However, this decision will give significant budget relief for Indonesia and substantially improve its debt position in the future.

Data from the Finance Ministry show that between 2014 and 2017 spending on education, health and infrastructure increased by 11%, 54% and 118%, respectively. Spending on the fuel subsidy decreased by 77% during the same period.

Such budget strategy represents good spending decisions by the government. This spending will create what classical macroeconomic theory argues as sustainable long-term growth with an increase in standards of living resulting from an increase in productivity.

Productivity is strongly determined by an improvement in both infrastructure and the quality of the human capital. By spending most of the budget on infrastructure, education and health sectors, Jokowi is on the right track to stimulate productivity. As productivity increases and the economy grows at a faster rate, we further believe that Indonesia’s debt position will be enhanced in the future.

Final verdict

The accumulation of Indonesia’s government debt ought to be treated with some caution. The Greek experience has presented lessons for countries to re-evaluate their approaches to debt management.

In the period leading up to the presidential election, the debt issue in Indonesia has been very much politicised. However, we do not see it as a threatening economic concern.

The debt-to-GDP ratio of Indonesia is still within a sustainable limit. Indonesia is also moving in the right direction to effectively utilise its debt. Three major international credit rating agencies agreed with such a verdict. Indonesia’s sovereign credit rating was recently upgraded.

There is of course room for improvement as the country continues its struggle to raise taxation revenue, improve bureaucratic efficiency and fight against corruption.