The result of April’s Iraqi parliament election may have been announced in mid-May, but there is still no sign of compromise among the deeply divided parties and blocs.

Many of prime minister Nouri al-Maliki’s critics were expecting his State of Law coalition, an offshoot of the Shiite al-Daawa Party, to lose its parliamentary majority. His previous Shiite allies and today’s opponents are to form a coalition to oppose a third term for al-Maliki, who has been ruling since 2005.

But al-Maliki’s opponents were disappointed. In the polls, his list still won far more seats in the forthcoming parliament than any other – but with only 92 out of 328, still came far short of anything like a majority. This forced them into another round of fraught negotiations to cobble together a coalition, just as in 2010 – and just as in 2010, it is proving to be a long and painful process.

Pressure cooker

As the negotiations began their heated and chaotic course, Iran began to exert pressure on Shiite leaders al-Hakim and al-Sadr to come together with al-Maliki and form a new government as quickly as possible.

It goes without saying that Iran’s influence on these people, and on the whole Iraqi political process, is enormous. It was Iranian pressure that kept al-Maliki in his post for a second term in 2010, when he convinced his Shiite opponents to settle with him. On top of that, Iran’s representative in Iraq, Qassim Sulaimani, head of the al-Quds Brigade and dubbed the strongest personality in Baghdad, arrived ten days before the election. He is still there now, trying to reconcile the differences between the Shiite alliances.

In the meantime, after the announcement of the results, most leaders of the expected winning lists started to change their tone from totally opposing any co-operation with al-Maliki’s bloc to proposing negotiations for the best person to fill the post of prime minister. In other words, they are ready to accept a leader from al-Maliki’s State of Law list – just not al-Maliki himself. al-Sadr, for one, has refused to support the State of Law unless the president steps down.

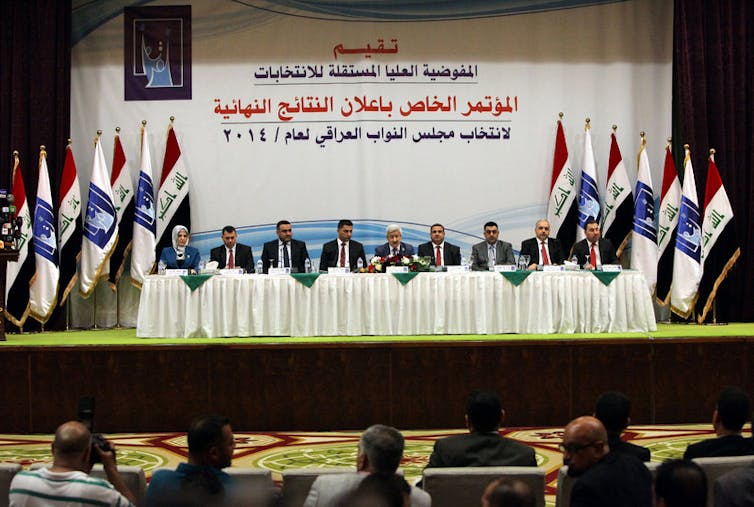

But for now, it seems al-Maliki is doing everything he can to remain in office, including influencing the High Electoral Commission (HEC) to manipulate the results. The HEC has twice revised the voter turnout figure: first announced as around 58%, it then jumped to 63%, and was then revised to well over 70%. That relatively high figure looks bizarre given the difficulties that prevented many areas from voting, for which many Iraqis directly blame the government. The extreme delays in announcing the final results were another indication that the election was anything but transparent and fair.

And the longer al-Maliki is allowed to remain in power as a caretaker prime minister, the longer he will have to lure more members of parliament into supporting him for a third term.

Taking sides

To make matters worse, all the names tipped for the premiership to replace al-Maliki are tarnished. The only exception is the Sadrist nominee, Ali Dawai, the present governor of Missan province, who distinguished himself as a good administrator. But all the possible leaders, including al-Maliki, are members of sectarian and religious parties, and will do nothing to temper the Sunnis’ sense of marginalisation.

Any of the candidates would spend their time in office largely subordinated to their religious institutions and leaders, which could easily fuel the sectarian division and tension in the country (to say the least).

The other problem is constitutional. The president of the republic is constitutionally meant to call on the leader of the winning list to form the government. But it is a well known fact that the Iraqi president, Jalal al-Talbani, has been absent for over a year due to ill health.

Nobody, including the government, seems to know anything about his whereabouts and his health condition. His first deputy, Tariq al-Hashimi, has been accused of terrorist acts, and has left the country; his second deputy, Khudair al-Khuzai, is a member of al-Maliki’s list, and may well hesitate to pass over al-Maliki in favour of someone else.

The other alternative is to wait for parliament to choose a new president. But it would also be a long time before a consensus on a new president could be reached, which would add yet another delay.

More of the same

Given al-Maliki’s determination to remain in power, it pays to consider the prognosis for Iraq if he manages to secure a third term. Going by his performance over the last eight years, Iraqis can expect corruption, chaos, poor public services, terrorist attacks, and general instability – to say nothing of al-Maliki’s sectarian and parochial policies, the marginalisation of Sunnis, the unresolved issues with the Kurdistan Regional Government, and other provinces’ complaints of neglect by the central government.

Much as he was in the 2010 negotiations, al-Maliki is clearly prepared to offer concessions to those opposing him in exchange for holding on to power. It remains to be seen whether his opponents can be tricked twice. And it is unclear how united and strong Iraq’s government can hope to be once his eventual partners take whatever concessions he offers.

The shadow of disintegration and full-scale civil war will only loom larger over Iraq until a strong and acceptable government is established. Given the extremely dangerous situation in western Iraq, the vacuum of power created by this post-election street-fighting will only allow terrorism the chance to spread to the rest of the country.

Whatever the future government will look like, it surely will not be an efficient technocrat one; it will be made up of people from the coalitions that provide the prime minister (whoever it is) with the votes they need. And ultimately, the Iraqis have chosen to be governed by the same sectarian, religious and corrupt representatives that have governed them since the fall of Saddam. Soon they will be kicking themselves for once again making that choice.