How do we account for forces and events that paved the way for the emergence of Islamic State? Our series on the jihadist group’s origins tries to address this question by looking at the interplay of historical and social forces that led to its advent.

Today, historian of Islamic thought Harith Bin Ramli explains how Islamic State fits – or doesn’t – in Muslim theological tradition, and incidentally addresses a question often levelled at adherents of the religion living in the West.

For Muslims around the world, it’s become an almost daily heartbreaking experience to see Islam associated with all the shades of cruelty and inhumanity of so-called Islamic State (IS). It’s tempting to dismiss the group as lying beyond the boundaries of Islam. But this way of thinking leads down the same route IS has taken.

Let me explain.

Ever since the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632, there hasn’t been a single central authority that all Muslims have unanimously agreed on. The first generation of Muslims didn’t just disagree, they battled over the succession to leadership of the community.

The result of this division was the formation of the main Sunni and Shi’i theological traditions we see to this day. But the blood spilt over the issue also resulted in a general sense of concern about the consequences of political and theological differences.

A consensus quickly emerged over the need to respect differences of opinion. And it was considered important to “disassociate” oneself from anyone who had differing views on these key issues. But as long as the person in question affirmed the basic tenets of Islam, such as the unity of God and the prophecy of Muhammad, he or she was still considered a Muslim.

Similar detractors

The one dissenting theological view on this matter was held by a group known as the Kharijites. It adopted the view that dissenting or corrupt Muslim leaders, by their actions, had become “apostates” from Islam altogether.

Sub-factions of this group increasingly extended their definition of apostasy to include any Muslim who didn’t agree with them. They declared these Muslims infidels who could be killed or enslaved.

The brutality of these extreme Kharijites never attracted more than a minority of Muslims, and other Kharijites adopted a more peaceful position more in line with the emerging consensus.

Widespread horror at the early divisions of the Muslim community and the terrors unleashed by Khariji extremism ensured that Islam generally embraced a pluralistic approach to differences of opinion. This emerged hand in hand with a culture of scholarship, based on the idea that the endeavour to seek the “true” meaning of scripture is an ongoing and fallible human effort.

Beyond a number of issues over which there was unquestionable consensus, different interpretations could be tolerated.

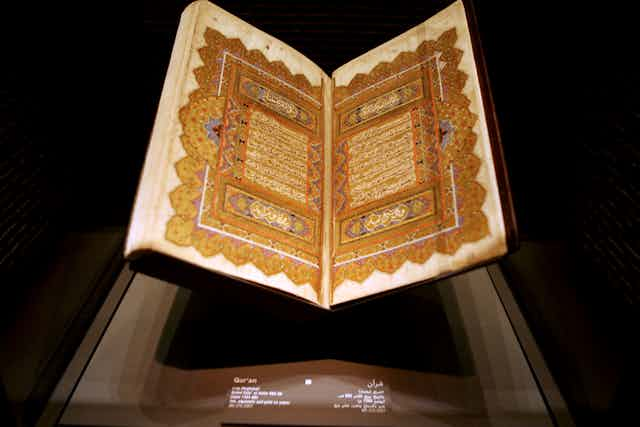

What makes IS different to traditional Islam isn’t necessarily the religious texts the group uses. To justify their practice of slavery or war against non-Muslims, they appeal to parts of the Qur'an or prophetic traditions, or legal works that are fairly mainstream and representative of the medieval Islamic tradition.

But these texts – scripture or otherwise – have always been read through the mediation of past and continuous efforts of interpretation by communities of scholars. As theology scholar Sohaira Siddiqui of Georgetown University points out, groups like IS deviate from mainstream Islam by their rejection of this culture of scholarly interpretation and religious pluralism, that is, the means by which the texts were interpreted.

This approach has roots in the group’s main theological inspiration, the Wahhabi movement. Founded on a radical interpretation of the 14th-century theologian Ibn Taymiyya, it dismissed any Muslim who didn’t subscribe to its strict interpretation of monotheism as an “apostate”.

It can also be traced back to radical political theorists of the 20th century, such as Sayyid Qutb, who rejected the modern state and attendant ideologies, including nationalism and democracy, as “idolatrous” and not based on the rule of God.

By declaring the revival of the Caliphate, IS claims to have created an alternative to the prevailing political order.

Harms of hastiness

Adopting a simple “with us or against us” approach lets IS justify denouncing Muslim rulers as “tyrants” and the religious figures who support them as “palace scholars”. In general, Muslims who don’t “repent” and support their beliefs are at risk of being denounced as “apostates” who can be killed.

Effectively, the group has revived the age-old Kharijite tendency in the form of a deadly modern political ideology.

IS is right about one thing: the solution to the widespread problems of the Muslim world cannot lie in the reaffirmation of status quo politics and the hypocritical employment of religion to prop up corrupt and oppressive regimes.

But its dismissal of the culture of scholarly pluralism and religious tolerance seems like an easy way to select interpretations of the scripture and religious tradition to suit its political aims, not the other way round.

Leading Muslim religious authorities, such as the Grand Shaykh of al-Azhar, have refrained from denouncing IS as “apostates”, even though they have called for the use of full military force against them. Their hesitance may be due to an awareness that such a move would simply drag the Muslim community down to the level IS wants them to be on.

Instead of labelling IS un-Islamic, the global Muslim community would do better to reaffirm its commitment to its culture of pluralism. This approach may also open up a crucial conversation that must take place about the relationship between state and religion in contemporary Muslim societies.

Many Muslims might share the IS view that there are already many signs that the end of times is approaching. But the group departs from mainstream Muslim apocalyptic theology in two respects.

First, its literature seems to omit any mention of the awaited Mahdi (the Guided One) and the return of Jesus the son of Mary, who is prophesied to defeat the Great Pretender (Dajjal, or anti-Christ). And second, in contrast to the average Muslim believer who acknowledges only a limited ability to fully grasp the meaning of these prophecies, IS arrogates for itself a central role in the unfolding of such events.

In other words, instead of waiting for God to bring about the end of times, IS hopes to prompt it through its own actions. In this respect, it has something in common with extreme forms of Christian and Jewish religious Zionism.

If one were to give IS’s followers the benefit of the doubt, excluding those with mainly criminal motives, it seems that theirs is an ideology fuelled by a hasty desire for the implementation of the will of God. And an even hastier dismissal of the more careful and humble approach of other Muslims.

As the Qur’an states:

“man was created hasty by nature” (21:37), and “all mankind is at loss, except for those who believe and advise one another concerning the Truth, and concerning patience”. (103:2-3)

This article is the second in our series on understanding Islamic State. Download our special report collating the whole the series.