With taxes, health care and climate change emerging as key issues in the upcoming federal election, we’re running a series this week looking at the main issues that swung elections in the past, from agricultural workers’ wages to the Vietnam War. Read other stories in the series here.

As far as 1960s policy issues go, none were bigger than the Vietnam War. Images of helicopter gunships and long-haired protesters overlaid with rock music are the era’s stock footage. But, was it ever a major election issue in Australia?

In November 1966, an Australian Labor Party that had been in opposition for 17 years finally saw victory within its grasp. And the party’s ageing leader, Arthur Calwell, focused on the war as Labor’s main point of difference with a seemingly divided, aimless government.

Organisations like the Australian Peace Council, Save our Sons and the Youth Campaign Against Conscription pushed hard for a Labor victory. But, in the end, Prime Minister Harold Holt not only won the contest, his Liberal-Country Coalition actually gained 10 seats, leaving Labor to lick its wounds.

Read more: Student protests won't be the last, and they certainly weren't the first

Australia’s involvement in the war

Australia’s involvement in Vietnam began in 1962. What started as a 30-person training deployment quickly grew to a battalion after then-Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced – inaccurately at the time – that South Vietnam had requested further assistance in its defence against the North Vietnamese-backed communist insurgents in April 1965.

This was a strategy of “forward defence” that marked Menzies’ policy towards Asia, which was widely supported by the Australian electorate as a way to stop the spread of communism across Southeast Asia. This strategy mirrored fears of a “domino theory” that would bring communism to Australia’s shores.

However, conscription was not as popular as the war among Australians. Polling in October 1966 showed that the public opposed conscription for overseas service by about 60%. Calwell, who had been the Labor leader since 1960, knew this and made it the most important issue in the next election.

Menzies’ retirement in January gave Labor confidence going into the 1966 election. Holt was a relative unknown who barely differed from Menzies on policy. At the same time, Labor was modernising its platforms by doing away with things like support for the “White Australia” policy.

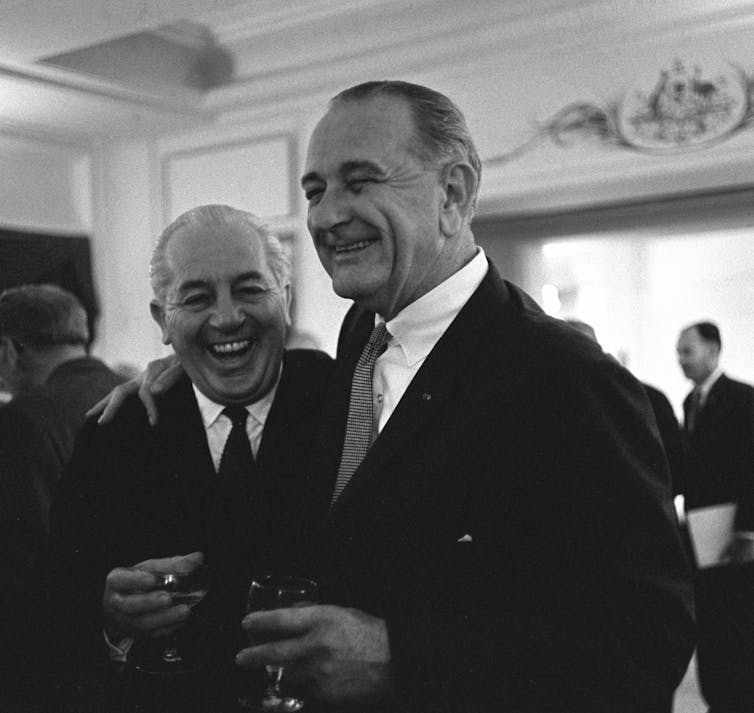

Also, an October 1966 visit from US President Lyndon B. Johnson, which Holt hoped would buoy his chances, was marred by anti-war protests that were broadcast around the world.

Labor’s failed conscription tactic

Yet, if anything, the focus on conscription showed not Labor’s revival but its continued stagnation. During the first world war, Calwell had been involved in the defeat of conscription in two national referendums in 1916 and 1917. Fifty years later, Labor hoped to use the timing of the anniversary of those defeats to its political advantage.

Speaking in April 1966, Calwell cautioned that conscription was a “sinister word” for Australians that would “split the nation and leave the same bitter memories as did the referendum campaigns of 50 years ago”. Then, in a campaign speech only days before the vote, Calwell condemned those who wished to plunge their “arthritic hands wrist deep in the blood of Australian youth”.

While not particularly innovative politically, Holt’s relative youth and seeming vigour – demonstrated by somewhat salacious photographs he took on the beach with his young daughters-in-law – seemed a breath of fresh air.

But this was just one of the reasons Calwell’s rhetoric fell flat. The audience for his messaging was also unclear. Australia was an increasingly youthful nation, but the voting age of 21 meant the “baby boom” generation had little electoral weight.

And while growing numbers of young people were protesting the war, they did so without reference to the first world war, but with theatrical protest tactics from overseas.

Legacies of the 1966 election

Holt’s unexpected landslide victory – winning twice as many seats as his opponent –proved politically explosive. While receiving little credit for the win, which most put down to Calwell’s ineptitude, Holt used his remaining year in parliament to cement an independent reputation through such initiatives as the May 1967 referendum on Indigenous rights.

His disappearance off Cheviot Beach in December of that year left an unfinished legacy.

Read more: The photographer’s war: Vietnam through a lens

As for the antiwar movement, Labor’s election failure led to disenchantment and reorientation. Increasing numbers of young agitators saw the result as a sign of deep public apathy with the movement. This led to more provocative and controversial protests, such as the daubing of soldiers with fake blood during parades, raising money for the Viet Cong and rioting outside the US Consulate in Melbourne.

Labor largely went quiet on Vietnam after its defeat, only returning to the barricades in time for the Moratorium marches of May 1970, by which time public opinion had finally turned against the war. It has been said that the 1966 election’s most significant legacy was as

the last stand of a distinctive Labor style - impassioned, traditionalist [and] Irish-Catholic.

Calwell’s post-election position proved untenable and he was replaced by the deputy leader, Gough Whitlam, who would spend the next five years modernising a party many considered stuck in the past. In the end, Calwell’s overzealous commitment to wielding the past as a political weapon only fast tracked this process.