With much fanfare, Barbados officially became a republic, installing Dame Sandra Mason as the first president of the island nation on Nov. 30, 2021. Then-Prince Charles, as a representative of his mother Queen Elizabeth II, was in attendance, providing a royal seal of approval. Barbados gained its independence in 1966, though the new nation kept ties to its former overlords by keeping the British Monarch as a symbolic head of state.

To many Bajans (inhabitants of Barbados), the move to republicanism represents an important attempt by the state to, in the words of youth activist and founder of the Barbados Muslim Association, Firhaana Bulbania, cast off “the mental chains that continue to persist in our mindsets.”

The ancestors of most Bajans lived in literal chains. The first English colonizers arrived in Barbados in 1625 and began importing huge numbers of enslaved Africans to work on the island’s sugar plantations from the 1630s. Their struggle to sever colonial ties with the British has been going on for nearly 400 years.

Bussa’s rebellion

The Bajan independence movement traces its roots to Bussa’s Rebellion, an enslaved revolt that occurred in 1816. That rebellion erupted on April 14, Easter Monday, when an enslaved driver named Bussa led an army of insurgents against the British colonial militia and garrison, burning cane fields and destroying property for nearly two weeks before the colonial governor, James Leith, managed to restore order.

By the time the fighting had died down, Bussa’s soldiers had destroyed over one-fifth of the island’s cane fields and caused over £170,000 in property damage, approximately US$13 million in today’s buying power.

But they did not succeed. That took another 150 years, and removing the monarchy only happened this year.

The stately events of Nov. 30, 2021, were the culmination of a movement that began as a violent revolt against the representatives of a political regime and economy based on enslavement.

Very little is known about Bussa beyond his being named as the military leader of the 1816 uprising in survivors’ testimonies and that he was said to have died during the fighting. A driver named Bussa was enslaved on Bayley’s Plantation in southeastern Barbados at the time. A “driver” was selected from among the enslaved and acted essentially as an overseer. As such, Bussa had access to countless enslaved men and women on surrounding plantations.

Most of what is known about Bussa’s Rebellion comes from testimony from surviving rebels, reports from the Colonial Office and the recollections of Protestant missionaries present in Barbados at the time. These sources detail a familiar story of enslaved demands for emancipation and also a rebellion inspired by rumors of the Haitian Revolution of 1791.

A surviving flag

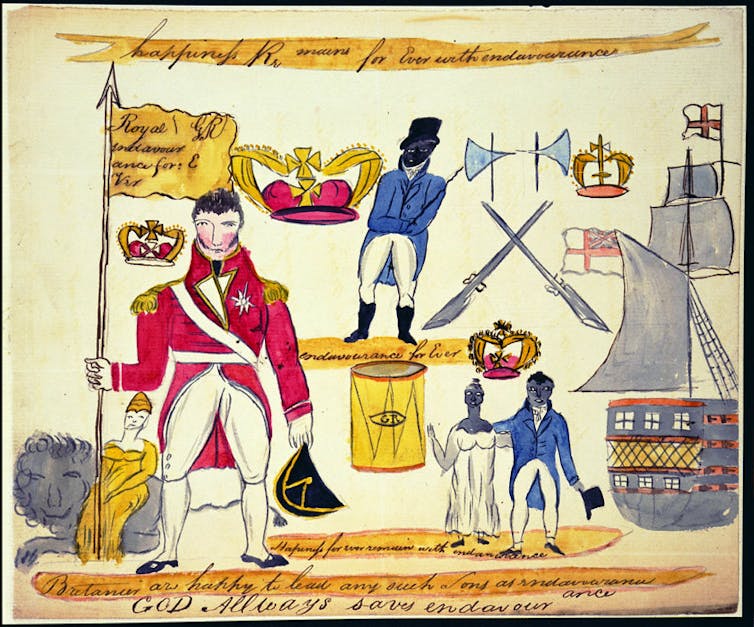

Bussa organized his rebels with an impressive degree of militarization, including the use of battle flags to coordinate attacks. Imperial soldiers found numerous banners and standards in their ransacking of enslaved dwellings. Edward Codd, commander of the island garrison, even recalled one that presented “a rude drawing that served to enflame the Passions, by representing the Union of a Black Man with a White Female.” Yet much of Bussa’s story is told in another flag, one that survived the rebellion in 1816.

The only surviving example of any of these flags, made by an enslaved rebel named Johnny Cooper, gives a complete explanation of Black attitudes toward emancipation, the actions enslaved Africans were willing to take to ensure their freedom, and most pertinently, what they expected that freedom to look like.

For example, Bussa’s rebels believed they had royal and divine approval. The flag makes this evident by presenting King George III waving a banner declaring “Royal endeavour and forever,” a phrase that would have been interpreted as support for the rebels.

Behind the king, Britannia herself sits on a British lion, commenting that she is “always happy to lead any such sons as endeavourance.” The enslaved revolutionaries similarly believed that “GOD always saves endeavour.” Bussa’s rebels evidently believed that the British monarchy understood and were sympathetic to their plight.

The presence of a Black woman on the flag alongside muskets and hatchets shows that the struggle against slavery was both a violent and universal one. The woman depicted is probably the likeness of a literate enslaved domestic servant named Nanny Grigg. Grigg was instrumental in planning Bussa’s Rebellion and was assigned the task of stealing newspapers from the plantation big house and reading them to Bussa and his lieutenants.

But most strikingly, this flag reveals what Bussa’s rebels expected their emancipation to look like. The Black man in the center of the banner has a larger crown than George III. This is likely a depiction of a free Black man named Washington Francklin, who the rebels had singled out as the post-emancipation leader of Barbados.

This is further underlined by the Royal Navy vessel exiting the scene eastward, back to Britain. In other words, Bussa and his followers expected emancipation to come with complete independence from imperial rule and the blessing of the British monarch.

This flag explains that in 1816, Bajans of African descent hoped for what was finally fulfilled on Nov. 30 2021.

Whither the Monarchy

Since independence from Britain in 1966, Bajans have wrestled with the question of their royal, distant head of state.

In 1979, the Bajan government published the report of the Cox Constitution Review Commission that concluded that a constitutional monarchy remained the preferred form of government.

Subsequent governments examined the possibility of republicanism in 2008 and 2015. Yet nothing came of these studies. It was the global reckoning with institutional racism from the summer of 2020 that inspired this constitutional shift.

Bussa’s coherent and revolutionary vision for Bajans of African descent from over 200 years ago serves as a lesson on endurance for those fighting for their rights. It is also a powerful reminder of a centuries-long history of Black struggles against institutional white supremacy and the ways they continue to resonate.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]