One hundred years ago, Europe stumbled into an unexpected and utterly devastating war. It was unexpected for two reasons: the diplomatic mechanisms set up after Napoleon’s defeat had kept the continent free from great power war in the 19th century, and that Europe’s economies had become profoundly intertwined.

War became possible because a rising power could not find satisfaction in the existing international order. Chauvinistic nationalism, a complacent mindset about warfare and non-existent diplomatic efforts to reduce the risks of conflict dragged Europe to war.

For some, history seems on the cusp of a tragic repetition. China appears to have all the trappings of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s Germany. It is a great power that is increasingly dissatisfied with the dominant order and is now able to deliver on its potential and ambition. The US is cast as an overstretched Britain: not quite aware of its limits and overconfident of its ability to see off challengers.

A confident and nationalistic Japan is one possible catalyst for conflict. Its alliance with the US is reminiscent of the complex arrangements that caused an assassination in Sarajevo to lead to World War One. The rumbling from North Korea, itself an ally of China, is touted as another spark that might ignite conflict.

Asia is cast as a region as complacent about the risks of war as Europe was in its belle époque. Analogies are an understandable way of trying to make sense of unfamiliar circumstances. In this case, however, the historical parallel is deeply misleading.

Asia is experiencing a period of uncertainty and strategic risk unseen since the US and China reconciled their differences in the mid-1970s. Tensions among key powers are at very high levels: Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe recently invoked the 1914 analogy. But there are very good reasons, notwithstanding these issues, why Asia is not about to tumble into a great power war.

China is America’s second most important trading partner. Conversely, the US is by far the most important country with which China trades. Trade and investment’s “golden straitjacket” is a basic reason to be optimistic.

Why should this be seen as being more effective than the high levels of interdependence between Britain and Germany before World War One? Because Beijing and Washington are not content to rely on markets alone to keep the peace. They are acutely aware of how much they have at stake.

Diplomatic infrastructure for peace

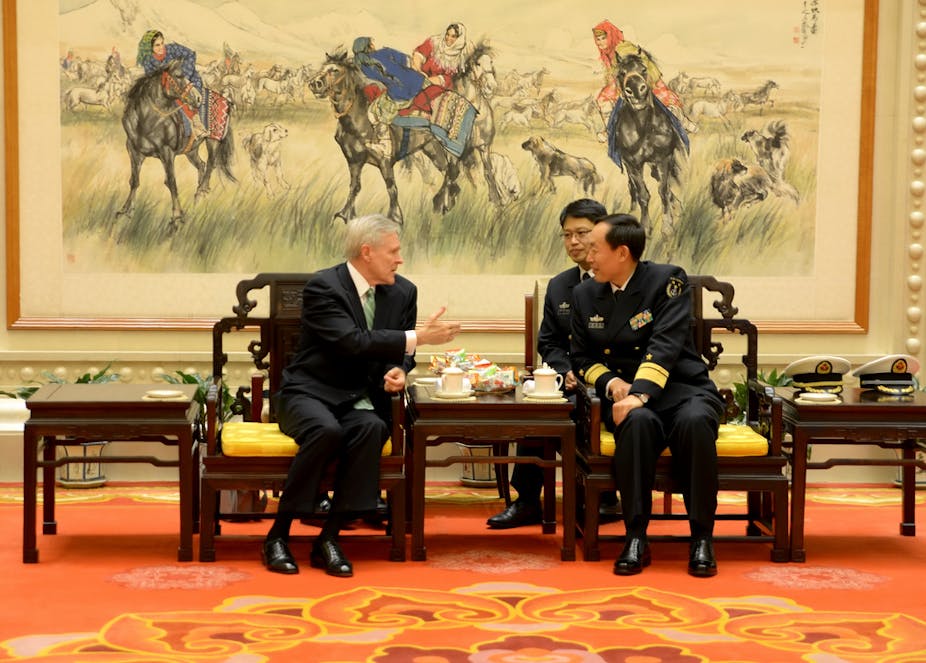

The two powers have established a wide range of institutional links to manage their relations. These are designed to improve the level and quality of their communication, to lower the risks of misunderstanding spiralling out of control and to manage the trajectory of their relationship.

Every year, around 1000 officials from all ministries led by the top political figures in each country meet under the auspices of the Strategic and Economic Dialogue.

The dialogue has demonstrably improved US-China relations across the policy spectrum, leading to collaboration in a wide range of areas. These range from disaster relief to humanitarian aid exercises, from joint training of Afghan diplomats to marine conservation efforts, in which Chinese law enforcement officials are hosted on US Coast Guard vessels to enforce maritime legal regimes.

Unlike the near total absence of diplomatic engagement by Germany and Britain in the lead-up to 1914, today’s two would-be combatants have a deep level of interaction and practical co-operation.

Just as the extensive array of common interests has led Beijing and Washington to do a lot of bilateral work, Asian states have been busy the past 15 years. These nations have created a broad range of multilateral institutions and mechanisms intended to improve trust, generate a sense of common cause and promote regional prosperity.

Some organisations, like the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), have a high profile with its annual leaders’ meeting involving, as it often does, the common embarrassment of heads of government dressing up in national garb.

Others like the ASEAN Regional Forum and the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus Process are less in the public eye. But there are more than 15 separate multilateral bodies that have a focus on regional security concerns.

All these organisations are trying to build what might be described as an infrastructure for peace in the region. While these mechanisms are not flawless, and many have rightly been criticised for being long on dialogue and short on action, they have been crucial in managing specific crises and allowing countries to clearly state their commitments and priorities.

Again, this is in stark contrast to the secret diplomatic dealings in the lead-up to 1914.

Higher risks, greater caution

States in Asia today are far more cautious about the way they use force than Europeans were in 1914. A century ago, war was seen as not only a legitimate policy choice but was championed by many for its ability to demonstrate national virtue, honour and prowess.

The experiences of war in the 20th century, the legal prohibitions that states have since created and the professionalisation of armed forces have meant that there is not the same taste for war that existed 100 years ago.

Asia is not about to succumb to a great power war because of the existence of nuclear weapons. The destructive power of these armaments focuses the mind of decision-makers on the consequences of using force in any significant way. Their existence acts as a crucial moderating influence on the policies of Asia’s great and aspirant great powers.

This is not a counsel borne out of complacency – the region has very real problems, which require careful and active management. Tensions in the East and South China Seas over tiny islands do have very significant risks of friction and conflict escalation. A nuclear breakout in northeast Asia remains an unlikely but nonetheless real possibility, while the old flash-points of Taiwan and Kashmir remain.

The region will require a great deal of vigilance to keep the peace. But it is an awareness of this effort that marks perhaps the final point of contrast with pre-war Europe.

Asia’s statesmen and women are well aware of the challenge that confronts them. So far we must pay them the credit of being up to that challenge and being capable of taking the necessary steps to ensure devastating war does not return.

We live in difficult times, but Asia is not about to sleepwalk into conflict.