The US killing of Iranian military commander Qassem Soleimani and Iran’s announcement that it will no longer abide by restrictions on enrichment agreed under the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement mean that it’s now time for the UK to reexamine its support for that deal.

Agreed in 2015 between Iran, the UK, US, France, Russia, China, Germany and the EU, the nuclear agreement – known officially as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) – provided a basis for a better relationship with the Islamic Republic.

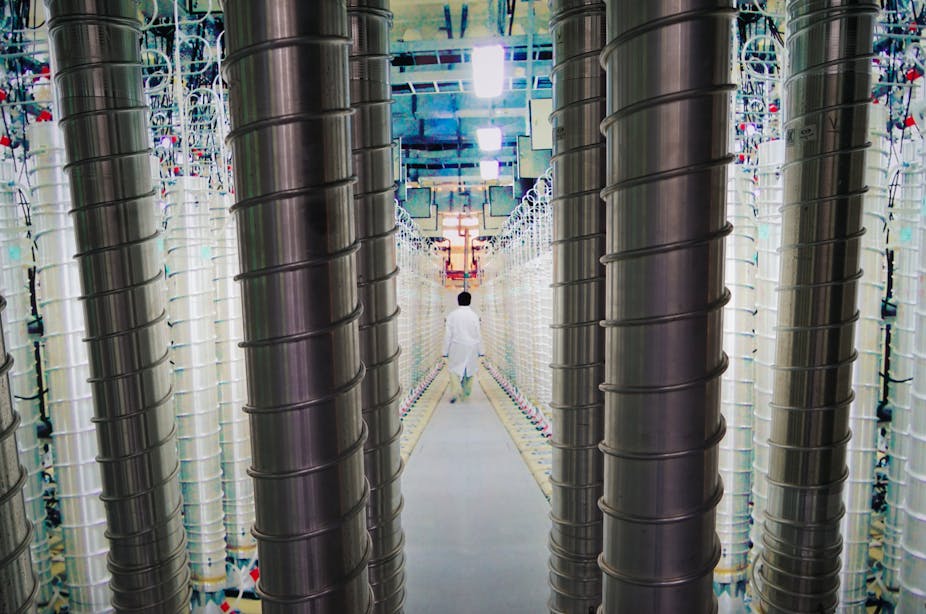

The agreement helped ensure that Iran didn’t move forward with its interest in acquiring nuclear weapons. It was painstakingly negotiated by leading powers, benefiting heavily from the UK’s technical expertise on nuclear matters, including my own. The deal was hard won – the result of years of increasing economic pressure and coordinated diplomatic initiatives. It effectively cut off every pathway for Iran to get the bomb.

These facts led the UK and its European allies, France and Germany, (known as the E3) to continue to support and champion the agreement even after the US president, Donald Trump, withdrew the US from the agreement in 2018. With the UK’s support, the E3 created new mechanisms to skirt reintroduced US sanctions, including a payment system to allow continued trade called INSTEX. The UK took this action in spite of US pressure because it was clear that upholding the JCPOA was in the UK’s interests.

We are only a few days into 2020 but already circumstances have changed such that the UK’s full-throated support of the JCPOA must now evolve. That is not to say that the UK should withdraw its support – at least not yet. Instead, I believe it should change its stance so that it is reviewing its position while watching for signs that Iran is committed to implement the letter and spirit of the agreement.

This nuanced wording is intended to provide the UK with flexibility while also pursuing specific interests.

Why the situation has changed

Before examining these, it’s useful to recap the two key recent developments. First, regardless of your reaction to the US airstrike in Baghdad which killed Soleimani, this use of force creates a new paradigm for relations with Iran that cannot be ignored. The killing of a uniformed military official of a foreign country is a de facto act of war, and Iran said it would retaliate. While escalation is not in the British national interest, nor would be continuing to support the JCPOA if Iran were to commit egregious acts against the US.

Second, on January 5, a few days after the killing, Iran announced it was taking another step back from full implementation of the JCPOA – this time by unilaterally removing the restrictions on enrichment capacity which were a central element of the agreement. This was but the latest in a series of step backs from Iran’s commitments intended to pressure other parties to fully implement the agreement including with regards to the easing of sanctions.

It is understood that the Iranian action was already planned before Soleimani’s killing to pressure the EU to further facilitate circumvention of the ongoing US economic sanctions. However, the step must also be understood in the context of Iran’s domestic political need to respond to Soleimani’s assassination.

This leads to the question of what approach the UK should now take. Britain is an important player with regards to Iran, not least because of its formal role in the JCPOA and seat on the UN Security Council. Britain holds the power to unilaterally cancel the agreement and reintroduce sanctions against Iran. Britain’s decision-making calculus will be influenced primarily by Iran’s compliance (or otherwise) with the terms of the agreement. But in practice, the UK’s position will be informed by broader aspects, including Iran’s actions outside of the agreement.

A nuanced position

It is for this reason that I argue that the UK should now evolve its stance on the JCPOA into one in which it is reviewing its position. This would allow the UK to pursue a number of otherwise competing objectives.

First, this move to review the UK’s stance could be taken without prejudice to any E3 decision to formally trigger the JCPOA’s dispute resolution mechanism in the weeks and months ahead – an approach which is now being discussed. The modalities of that process mean that, once triggered, it is likely to lead to a formal end of the JCPOA.

Second, it could support maintenance of the JCPOA – at least in the immediate weeks ahead, and perhaps for longer. If the UK were to fail to take any action now to mark its objection to Iran’s breach of the agreement, its ability to object later on would be hindered.

Third, the UK should state that it is looking for signs that Iran intends to comply with the letter and spirit of the JCPOA in creating an enduring improvement in relations with an Iran free of nuclear weapons. This phrasing is carefully chosen. Iran would understand that any egregious action against US forces would be taken in the UK as a negative sign. But the UK would maintain a degree of ambiguity regarding the level of Iranian action which might trigger it to withdraw from the JCPOA. While the nuclear issue should be kept separate from other issues, for example, the illegitimate imprisonment of British dual-nationals in Iran such as Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, the Iranian regime would also understand that its actions were under scrutiny.

This approach should buy the UK some time to see how the situation evolves and whether escalation would necessitate a further re-evaluation. But the UK needs to help find a path forward. The purpose of the JCPOA was never to fully solve the Iran nuclear issue in the long term – its purpose was to buy time for relations to improve and broader understandings with Iran to be achieved.

Based on the timeline set out in the agreement, restrictions on Iran’s activities are scheduled to start easing from later 2020, despite no parallel signs of relations improving. Over the course of the weeks and months ahead the UK must decide whether the JCPOA is salvageable, whether a broader understanding can be achieved and what the implications are if not. The UK will have to engage with the US, its European partners and Iran in order to understand the outlook for the agreement. It can’t assume that it’s a positive one.