The death of Jacques Chirac leaves us with a paradox. He was the most popular president of the Fifth Republic, and yet one without any notable achievement during his tenure as leader.

Of course, the obituaries will judge him leniently. They will emphasise his success in resisting American pressure during the second invasion of Iraq – for which he does indeed deserve much credit. But what else is there? Chirac’s political career spanned nearly 40 years at the highest levels of government – he was president for 12 years, between 1995 and 2007, and served as prime minister for two terms (1974-76 and 1984-86). Yet a close analysis of his legacy leaves us with the impression of a lack of tangible results, if not of a large void.

From bulldozer to idle king

Chirac began his political career in the ministerial teams of Charles de Gaulle and Georges Pompidou in the late 1960s. He was thereafter forever linked with Gaullism, even if his personality and political choices point to a much more ambiguous personal position.

His first major political triumph came in 1974 in the presidential election that followed the death of Georges Pompidou. Chirac outmanoeuvred his rivals to become prime minister to President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing.

But Chirac only held the post for two years before resigning. France’s postwar boom years (the “trente glorieuses”) were coming to an end. The country was exposed to its first oil crisis and suffered a long period of mass unemployment, alongside rampant inflation. The key changes that did take place under Chirac (lowering the voting age to 18, legalising abortion, reforming divorce laws) were largely ideas put forward by Giscard d’Estaing as a presidential candidate, rather than coming from Chirac in office.

This first, brief experience as head of government led Chirac to become distanced from the centre of political power for some time. He made do with the mayorship of Paris, a post he occupied until 1995 while founding a political party over which he exercised complete control – the Rassemblement pour la République (RPR). The party was Gaullist in its orientation and a forebear of the main party of today’s French right, les Républicains.

In 1981, Chirac failed to reach the second round of the presidential election, which was subsequently won by François Mitterrand. He became leader of the opposition and was subsequently appointed prime minister in France’s first “cohabitation government” in 1986-88.

Serving under the socialist Mitterrand was the first (but not last) breach of the Gaullist legacy, and one that even today can be interpreted in different ways. Did it stem from a thirst for power, political short-sightedness, a lack of self-discipline, pragmatism or overhastiness? Or was it, perhaps, a mixture of all of those things? Either way, the experience was marked by two years of confrontations with Mitterrand, who, unsurprisingly, exploited the situation to regain the political advantage and win the presidential election convincingly in 1988.

Finally, in 1995, at his third attempt, Chirac finally won the presidency – despite numerous acts of treachery from within his own camp by rivals keen to stop him.

His time in office was far from easy. Chirac drew international criticism at the very beginning of his seven-year mandate when he resumed nuclear testing in the Pacific. Then came strikes in the winter of 1995 and the ill-fated dissolution of parliament in 1997. After performing badly in the subsequent parliamentary election, Chirac was forced into a cohabitation that last until 2002. This time, he played the token president next to socialist prime minister Lionel Jospin.

In the end, it was only a fortunate combination of circumstances – a rising far right threat and a fractured left – that enabled Chirac to win his second term in 2002. He took 82% of the vote against National Front leader Jean-Marie Le Pen in the second round of the presidential election.

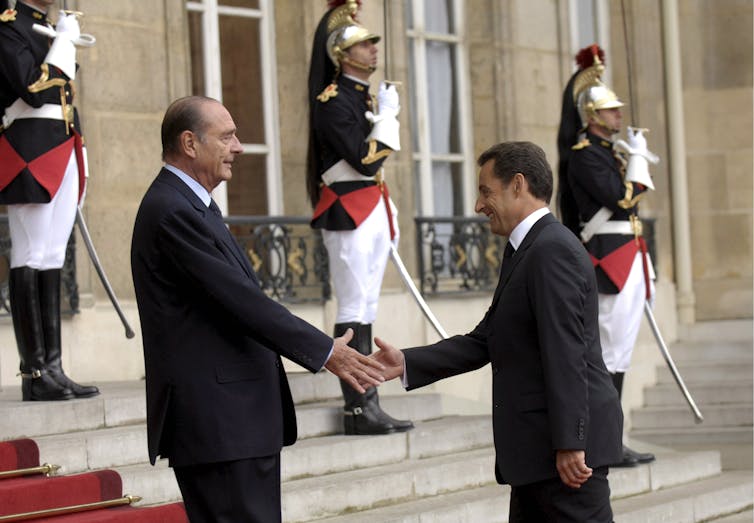

Despite taking the highest share of the vote ever, Chirac never quite managed to shake off the idea that he hadn’t been elected for the “right” reasons. This second mandate was characterised by apparent inactivity. To borrow Nicolas Sarkozy’s phrase, Chirac was beginning to look like an “idle king”.

Chirac was oddly silent for a long time during the serious urban riots of 2005. He then went on to lose a referendum on the European Constitutional Treaty. His second mandate was ending on a bitter note. He even faced a number of criminal charges and was subject to a string of book-length studies that were highly critical both of him personally and of his political actions.

The president of ‘French malaise’

The economic backdrop was not always unfavourable, yet Chirac’s France, increasingly vulnerable, globalised, fragmented, insecure and depressed, became mired in what academic Nicolas Baverez would call “les trente piteuses” (the post-1974 gloom years).

All things considered, it was under Chirac’s presidency that France’s “malaise” became firmly entrenched. It was a malaise that stemmed from long-term, mass unemployment, a crisis in French society and French identity, and a growing anxiety about the increasingly globalised world beyond its borders. Indeed, it was towards the end of Chirac’s mandate that the notion of “France’s decline” returned with a vengeance.

Chirac was right on the subject of Iraq, but we would be hard pressed to find any other major actions under his presidency. We might cite the French state’s acknowledgement of its role in deporting French Jews during World War II or the shift towards an active pro-European policy – but are either big enough to be called a defining moment?

The enigma

Although Chirac’s presidential legacy is limited, many people are fascinated by him as a person. He was a political animal, capable, like his nemesis Mitterrand, of overcoming defeat and betrayal and of eliminating his rivals.

They are fascinated, too, by Chirac the man. Warm, hardworking, likeable, energetic, down-to-earth, charming, cultured … there is no limit to the complimentary adjectives showered on him by those who came into contact with him. He was also a man open to the world and to all cultures. The Paris museum of tribal art, which he founded, will be an abiding testimony to that.

There is an almost equal amount of interest in the part of Chirac’s persona that remains hidden in shadow. Countless books have been written about “Chirac, the enigma”, and the majority of his many biographers concede that part of his personality is unquestionably shrouded in mystery.

The true nature of his political convictions are also a mystery. As a student, he flirted with the Communist party but then he went on to praise the economic liberalism of Reagan and Thatcher in the 1980s. In 1995, he campaigned on the subject of France’s social divide, but once elected initiated a conservative programme of deeply unpopular social reform. He also oscillated between euroscepticism and support for the EU project.

The same ambiguities are in evidence on the question of immigration and integration. Despite launching the controversial “regoupement familial” which authorised migrants to have their family joining them in France and steadfastly opposing the National Front, certain statements, including a comment about the “noise and smell” generated by African families, have left a lasting sense of unease.

We should also note the questions raised about the former president’s personal integrity. In 2011, he was given a suspended prison sentence of two years for abuse of trust, embezzlement of public funds and conflict of interest.

History may well have little to say about Chirac, associated as he is with a lacklustre period in France’s past. He was, at least a politician of his time. Certainly, comparison with his predecessors and successors will not always be to his disadvantage – but perhaps that says more about them than him.