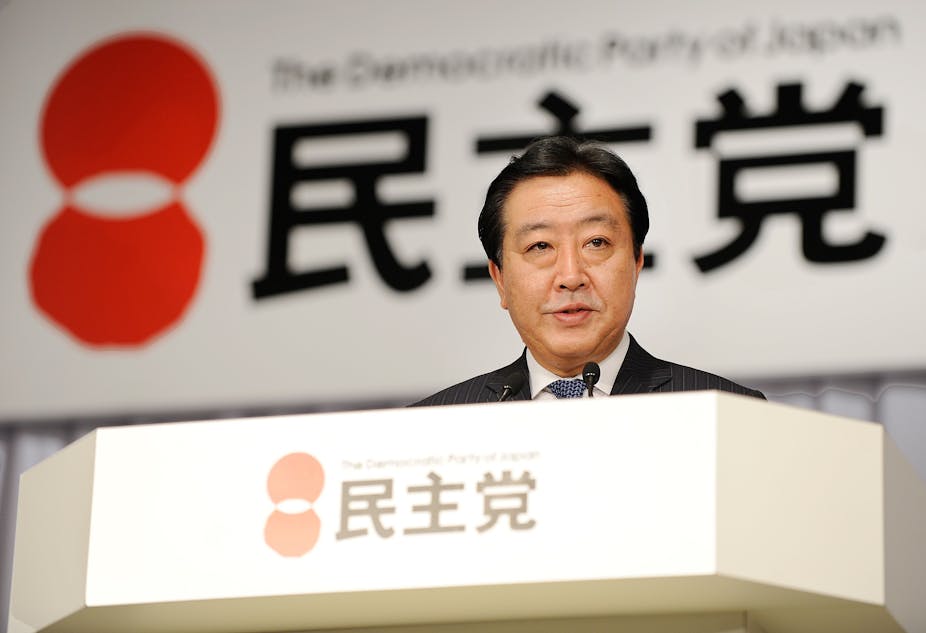

Former Finance minister Yoshihiko Noda has become Japan’s sixth prime minister in five years after winning a leadership vote in the parliamentary wing of his Democratic Party of Japan.

Noda replaces Naoto Kan, who has come under intense criticism for his government’s response to the March 11th earthquake and tsunami and associated nuclear crisis at Fukushima.

The Conversation spoke with Sydney University Adjunct Professor Richard Broinowski - a former diplomat posted in Japan - about what the ascension of Noda means for Japan as it works to recover from the diasters earlier in the year.

How is Noda different to his predecessors and what new thinking will he bring to the role?

It is an important question but I am afraid the answer is not much. This man is cut from a similar mould to all his predecessors although he claims to have a poor country cousin background and therefore to be quite different.

He likes to call himself self-deprecatingly as a loach, a deep water fish. He says he’s not a goldfish. So he’s got a maudlin sense of humour but frankly he doesn’t have a great deal going for him. I don’t think he is a man of much imagination or charisma.

I think that he has got some enormous problems to face. Being a former Minister for Finance is going to be helpful, he fully understands the economy and he is an ally of the outgoing Prime Minister Naoto Kan. I think he is going to be a hardliner and raise some taxes. We’ll have to wait to see what he does.

The other thing he’ll probably want to do is modify or reduce the country’s reliance on nuclear energy. This doesn’t mean he will face it now. In fact the power industry is so strong among the nine generating and distribution companies of which Tepko is the biggest, that I don’t think any Prime Minister without an enormous amount of public and party support behind him would be able to reduce to nothing nuclear power in Japan.

He’ll work out a compromise and he’ll do what he can within his lights.

Will this period of political instability in Japan end soon or is the new reality?

I think it probably is the reality. The fact is that Japan is based on a party system. The old Liberal Democratic party was riven by factions and people got resoundingly sick of them and chucked them out in the elections when the Democrats were appointed a couple of years ago.

The first thing they were going to do was abolish the power of the bureaucrats in Tokyo in the ministries. But that hasn’t happened. The bureaucrats still rule and they rule effectively. We don’t see any breakthrough here in my view. I wish we could but it seems to me that it is just more of the same.

The electorate are just as cynical and tired of the opportunistic conformity of the new lot as they are of the old. It is a far cry from saying they want the Liberal Democrats to come back again but they simply haven’t got a great deal going for them here.

Would you say there is a need for a fundamental generational change in the way Japan governs itself to deal with the crises on many fronts it is facing?

It is not so much a generational change as unfortunately the new breeds of politicians come out of the same moulds as their forefathers. We have a tribal system in Japan where there are obligations, there are things that have to be done, there are conventions that have to be followed and restrictions on behaviour.

It is hardly the atmosphere where one person can rise and become some kind of aspirational leader that breaks through barriers. We thought that might happen when the Democrats took power but that really hasn’t happened.

There are enormous challenges in Japan but one thing that has happened since the Fukushima reactor problem is that Western and foreign observers tend to see Japan as some kind of third world country. The poor little Japanese, look at what has happened to them, this awful triple whammy of the earthquake, the tsunami and the nuclear disaster.

The fact is that Japan remains the third largest and strongest economy in the world. They have poured enormous resources into handling their own disaster in Tohuko in the northern region of Honshu and yes there were foreigners involved but they were dwarfed by the efforts of the Japanese themselves.

The Japanese remain rich and powerful and capable of handling their own problems and paying for them. And that is what they have done.

They’ve got a political system that is crippled. But it has been crippled for a long time. In the early period after WWII, the golden age of the 1960s and the 1970s you had prime ministers like Sato who were able to hold a degree of conformity and consistency in government policy.

The policies are still going and the bureaucrats are still really running things and because of that, when you see such a change in prime ministers it does not necessarily signal – as it does in Italy – political instability because behind the politicians blustering as they do in the Diet, there is a solid well-educated effective bureaucracy that is really controlling what is happening in Japan.

Will his comments in support of Japan’s WWII leadership play badly with neighbours like South Korea and Japan?

Not necessarily. That depends on how it is handled. So many prime ministers in the past have said things like that, the war wasn’t our fault, we didn’t do bad things in China, we do need the atomic bomb for our own defence, all kinds of statements are made by right-wing politicians and they get away with it.

If he is saying similar things, well too bad. Whether it makes a difference to Japan’s relations with China, I couldn’t say at this stage. I don’t think it will. I think probably there is so much synergy between the countries [at the moment]. The Chinese were quite sympathetic to what happened in Tohoku and they shelved their resentment about the Japanese and their refusal to make a wholehearted apology for WWII.

There seemed to be some kind of constructive understanding going on. I think that will continue. South Korea, China and Japan have a very strong affiliation. They trade more with each other than they do with the rest of the world. That’s unlike another rising power in India which trades much more with the US and Europe than it does with its neighbours.

In north east Asia there is a synergy of countries that are achieving about the same things at about the same pace although Japan is the older grandfather and has fallen behind a bit.

They are very dynamic and they are working very well together and that will continue.