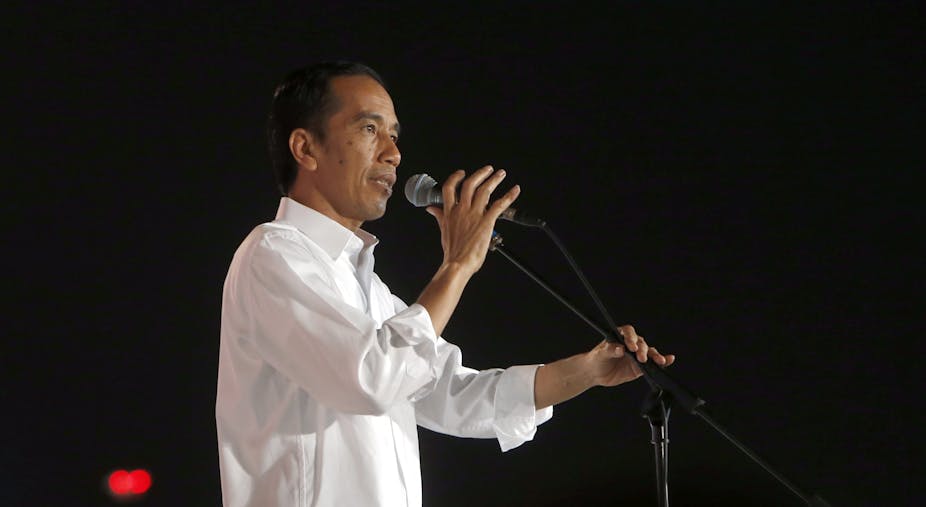

Indonesia’s president-elect delivered his victory speech in Sentul, West Java, on July 14 2019.

Jokowi ran for his second term in an election in which he competed once again against Prabowo Subianto. The two camps used religious identity narratives, polarising voters.

By analysing the choice of words that Jokowi used in his speech, we can see that he seemed to be attempting to end the political polarisation that intensified during the election. He also seemed to try to define the type of person that he deemed to be opponents and allies.

Unveiling messages through diction

From a linguistic point of view, political speeches usually contain explicit and implicit messages, used interchangeably based on what the speaker wants to achieve through their statements.

Explicit messages are straightforward. In language theory, they are expressed literally. In these messages, what is said represents the intended message.

In contrast, implicit messages are those that exist between the lines and are not communicated directly.

Understanding explicit messages is straightforward. Implicit messages are much trickier because they are often left unsaid. But we can find hints of these implicit messages by looking at the word choices a speaker uses in his or her speech.

The “we” politics

One of the most prominent words in Jokowi’s speech is the pronoun “kita” (the inclusive “we”).

Jokowi used the word “we” 61 times, 5.74% of all the words said. He used it far more often than words such as “must” (24 times) and “Indonesia” (23 times). “We” appeared more often than the conjunctions “which” (53 times), “and” (24 times), “will” (18) and “with” (15).

Apart from its frequency, Jokowi used “we” evenly at the beginning, middle and end of his speech.

Jokowi did not use the word “we” only when he was talking about the opposition and when he was talking about his vision.

According to my analysis, the high frequency of the word “we” reflected Jokowi’s intention to end the highly polarised political climate during the 2019 election.

The word “we” pragmatically has a more positive impact on emotional and social relationships between speakers and listeners. By using the word “we”, Jokowi was attempting to reduce any psychological distance with his political opponents. He was also inviting his supporters and Prabowo Subianto’s supporters to reunite.

According to two English linguistic researchers, Linda Thomas and Shan Wareing, the use of “we” has become a formula in political speeches. The word “we” is used when one party wants to identify itself as part of another.

The semantic opposites of the inclusive “kita” is the exclusive “kami” (also translates to English as “we”) and “mereka” (“they”); two words that are used in communication between ethnicities and groups that are in tension.

Jokowi’s choice of using the inclusive “we” is a planned and measurable strategy. He avoided using the word “they”, which only appeared at the end of the speech. Even in that sentence, “they” was negated. “This is not about me, nor you. Also not about us, nor them.”

Which is friend, which is foe

While using the speech to express his political vision, Jokowi also used the speech to declare who are his allies and his enemies.

Although it was disguised, Jokowi’s statement in identifying his opponents and allies could be analysed from the diction and the configuration of words he used.

The subjects he identified as allies were consistently depicted in sentences with positive nuances. He always referred to those he identified as enemies simultaneously with negative adjectives.

Jokowi used a number of positive words, namely “big” (used 9 times), “front” (6), “high” (5) and “productive” (3).

The negative words he used were “don’t” (5 times), “far” (2), “left behind” (1), “beat up” (1) and “disband” (1).

In linguistics, adjectives can be used to analyse sentiments. Adjectives have the emotional range from most negative to most positive.

The most negative words are “die” and “kill”, which are quantified with a value of 0. The word “love” has the most positive sentiment with a score of 1.

The way the speaker arranges positive and negative words implies his sentiment towards certain parties. Thus, we can recognise which party gets positive sentiment (favoured) and which one gets negative sentiment (hated).

The adjectives in Jokowi’s speech had a clear configuration pattern.

Jokowi used the word “big” to describe infrastructure and change, two concepts that were boldly underlined in his government. The word “high” was used to describe the talents and dignity of the nation. “Productive” was used to describe the country and age.

On the other hand, negative words were used to describe parties that he tends to dislike.

In the group of sentences that talked about the opposition, Jokowi used five negative words at once, namely “revenge”, “hatred”, “insult”, “scorn” and “curse”.

Five of the 40 words (12.5%) that Jokowi used when talking about opposition were negative words. This frequency showed a negative sentiment towards the opposition, even when he did not literally say it.

Jokowi used the word “far” to describe a future that is difficult to predict. He mentioned “beat up” in relation to complicated bureaucracy and extortion; and “disband” was used in relation to troubled government institutions.

By observing the patterns above, he was trying to embrace three parties, namely, those who support his infrastructure development projects, those who have great talents, and those who want change.

That pattern also consistently showed that Jokowi placed himself against the opposition (which spreads hatred), bureaucracy (which is inefficient) and government institutions (that are less useful).

The way Jokowi used his words aligns with the theory of Systemic Functional Lingustics (SFL). The theory states that the structure of language is strongly influenced by its social functions.

Words are not chosen by speakers just to express meaning; more importantly, they are used deliberately to arrange social relations and realise certain interests.

Las Asimi Lumban Gaol translated this article from Indonesian.