Josephine Baker – performer, Resistance hero, and civil rights activist – is the first woman of colour to enter the Panthéon in Paris, where her remains will be interred. She is is the latest hero of the French Republic to be “Panthéonised”. But what does it mean to enter into the “temple of the nation”, and how does this process work?

Panthéonisation, as the process is known, has its origins in the French Revolution. In 1791, the revolutionary National Assembly voted to transform the new Church of Saint Genevieve on the Left Bank of Paris into a “temple of the fatherland” where the nation’s great men would be honoured.

Panthéonisation is one of the highest honours the French Republic can bestow on its citizens. Between 1945 and 1981, such ceremonies were relatively rare. It is only in the last four decades, following the election of François Mitterrand as president in 1981 and his inauguration day visit to the monument, that it has become more common for French presidents to select people for the honour.

Why was it created?

The idea of creating a French national pantheon predated the revolution. It was inspired both by classical pantheons of the gods, and the model of Westminster Abbey as a space to honour national heroes. Unlike in Britain, however, the revolutionary Parisian Panthéon was to be a secular monument. An inscription on the front of the former church stated its new purpose: “To the great men, the grateful fatherland” (in French, “Aux grands hommes, la patrie reconnaissante”).

Throughout the revolutionary and Napoleonic eras, the Panthéon retained its function as a temple of great men (and they were all men).

Alongside politicians and soldiers, in 1794 the Enlightenment thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau joined Voltaire in the crypt, both honoured as intellectual forebears of the French Revolution.

Over the course of the 19th century, the fate of the Panthéon mirrored the upheavals in French politics. The building was by turns returned to the church and then reclaimed as a secular temple. It was not until 1885, and the death of the writer Victor Hugo, that the monument definitively assumed its status as a temple to the great and the good. Hugo’s funeral marks the first modern Panthéonisation. The remains of “Le grand Victor” were brought to the Panthéon through the packed streets of Paris in a spectacular, nine-hour procession.

What qualifies someone?

There are no strict rules about what qualifies someone for Panthéonisation, and the final decision is made by the French president. The 1885 legislation simply states that “the remains of great men deserving of national honours will be buried there”.

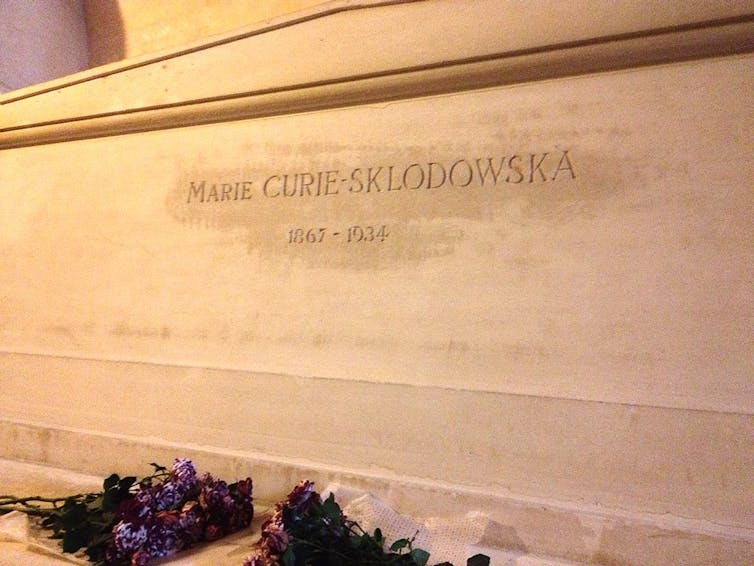

Napoleonic generals and politicians aside, the current occupants of the Panthéon’s crypt show how broadly this criteria can be interpreted. Politicians and activists, such as Jean Jaurès and Jean Moulin, are honoured alongside writers such as Émile Zola and Alexandre Dumas, and scientists, notably Marie Skłodowska-Curie and her husband Pierre. Skłodowska-Curie’s inhumation in the Panthéon, in 1996, was the first time a woman had been honoured there in her own right.

Panthéonisation is not limited to individuals – in 2007, those deemed “righteous among the nations” for their part in saving Jews during the Holocaust were inducted. And it is not essential for the person’s body to be physically interred there, either - the remains of poet and politician Aimé Césaire, Panthéonised in 2011, are buried in his native Martinique.

Josephine Baker’s selection marks a new departure in more ways than one – not only is she the first woman of colour to enter the Panthéon, but she is also the first performer. However, it is her Resistance and civil rights activism, rather than her popularity as an entertainer, that have secured her entry. During the Second World War, Baker worked in espionage for the French Resistance. Her celebrity status allowed her to move more freely to gather information and to transport documents without the risk of being strip-searched. In the 1950s and 1960s, she used her visits to her native United States to advocate for civil rights and racial equality, culminating in her appearance at the 1963 March on Washington. Dressed in her Free French uniform and proudly wearing her wartime medals, Baker urged young African-Americans to “light that fire in you” as they fought for civil rights.

For the public, the most visible and important part of the Panthéonisation process is the ceremony that accompanies the honoree’s entry into the crypt. In the century and a half since Victor Hugo’s triumphant burial, Panthéonisation ceremonies have become ever more personal, designed to reflect the life of the individual being honoured.

The entry in 1964 of the French Resistance leader Jean Moulin featured a torchlit procession, echoing Moulin’s description of the Resistance as a “people of the night”. The 2018 ceremony for the politician Simone Veil honoured her political achievements and status as a survivor of the Holocaust. Her coffin was brought up the rue Soufflot on a bright blue carpet, symbolising her election as the first president of the European Parliament. An audio recording of the dawn silence at the Birkenau camp site, where Veil and her mother were imprisoned, was played prior to the entry of her remains into the monument.

For Josephine Baker’s ceremony, her son, Brian Bouillon-Baker, called for a “musical, popular, festive” event, capturing his mother’s spirit as well as her achievements. Baker’s entry into the Panthéon comes after several years of a popular campaign and public petition and could mark a change in how people are selected for the honour in the future. The induction of a Black woman, born outside France, could herald a new and more diverse era for the Panthéon, ensuring the monument reflects both the history of the French Republic and the diversity of contemporary France.