The phrase “colonial settlement” sounds benign, but Julie Gough’s Tense Past presents compelling evidence to the contrary.

Since 1994, Gough has been searching the archives, piecing together the evidence and representing Tasmania’s overlooked history of dispossession and frontier war.

She has made art installations by collecting maps, correspondence and text, found objects and natural materials, and by recording her own movement – walking, running and driving – through her ancestors’ land.

Read more: Tasmania's Black War: a tragic case of lest we remember?

In this major exhibition, surveying 25 years of her work, Trawlwoolway artist Gough generously shares her own, and her family’s experiences as Tasmanian Aboriginal people to skilfully entwine the past with the present.

A legacy of early Australian landscapes

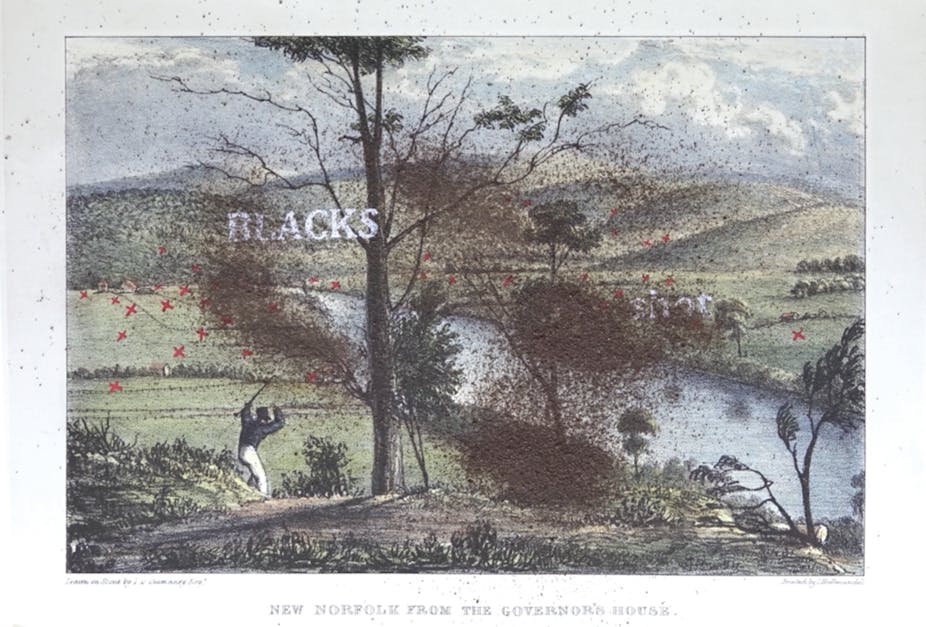

We understand our colonial history through art. In Hunting Ground Pastoral, Gough counters the bucolic and idyllic narrative of Australian colonial paintings.

Representing new lives in a “new” land, colonial painters like John Glover and Joseph Lycett helped to create — and continue to maintain today — an official story of peaceful settlement in their paintings of Australia.

Their early landscapes give the impression of Europeans farming a fertile and ordered countryside. Aboriginal people are generally not present at all, but if they are, they are portrayed in some parallel Antipodean Arcadia, living harmoniously in an environment unaffected by European settlement.

In this video, Gough corrects the visual record. She recreates hidden scenes from the Black Wars by animating a series of historic prints of familiar Tasmanian locations such as the village of Richmond, a major tourist destination just outside Hobart.

As the video progresses, each print is slowly inscribed with quotations from historical documents detailing a massacre that occurred at the same site:

Launceston … pursuit 12 miles … four men, one woman and a child killed.

Blood red arrows, crosses or circles appear beneath the superimposed words and a blood red stain seeps into the landscape. Each image is then slowly obscured by soil until it is completely buried, just as these colonial paintings in their gilded frames have painted out a history in which the hunting grounds of Gough’s ancestors become the site where they themselves were hunted and murdered.

Brutal dispossession

Curated by Mary Knights, Gough’s sculptures, videos and installations are deftly supported by colonial artworks and artefacts from TMAG and other major collections.

And just as Gough re-inserts Aboriginal resistance fighters into the landscape of the colonial painting, these genteel portraits, items of furniture, cutlery and letters remind us that Tasmanian history was not some abstract process, but a series of deliberate acts carried out by men and women of refined tastes.

Read more: Peta Clancy brings a hidden Victorian massacre to the surface with Undercurrent

The 1830 Black Line map graphically illustrates the tactical manoeuvres of a cordon of soldiers, police and settlers moving across the island north to south, attempting to force all remaining Tasmanian Aboriginal people off their land.

A campaign desk with a sealed box provides the staging to re-imagine the moment that the plan of attack was conceived, approved, activated and managed.

And in her piece, We Ran/I am, Gough gives human form to these brutal attempts to dispossess Aboriginal people and links herself to her ancestors. Retracing the Black Line on foot, she captures her own body running and stumbling in 14 still images.

Above the prints hang seven, earth-stained pairs of calico trousers that she recreated to resemble those described in a journal entry by the “protector” of Aborigines George Augustus Robinson as “excellent things”, because they made it impossible to run.

The first stolen generation

One of the most powerful ways in which Gough connects the past with the present is through the stories of children. In a sound installation she sings a Tasmanian Aboriginal children’s song, Song for the Aborigines, that was transcribed by Mrs Maria Logan in 1856. The historic manuscript is also displayed in the gallery.

But she also tells us about the first generation of stolen children, long before the term was first adopted, in her piece, “Missing or Dead”.

Over a ten-year period, Gough gathered the names of Aboriginal children who had been living with non-Aboriginal people up until 1840.

She identified more than 180 individuals and created a haunting memorial to these forgotten children by inscribing some of these names (including three of her ancestors) onto unfinished tea-tree spears.

Bundled together and constrained by the suspended frame of a broken chair, names like “Girl x”, “Goldie” and “Charley x” are burnt onto the bare wood, offering a sharp, poignant glimpse of their lives and so resisting their erasure from history.

Beyond the gallery, Gough extends this work in a temporary memorial that forms part of the Dark Mofo’s Dark Path program.

Read more: Explainer: how Tasmania's Aboriginal people reclaimed a language, palawa kani

More than 180 posters bearing the names of stolen and missing children are nailed to the trees in Queen’s Domain, referencing how proclamations were displayed in colonial times.

This work illustrates the tragedy and scale of child removal while also alluding to white anxieties about losing children in the Australian bush.

Gough tells us she has only been able to track ten of these missing children’s descendants through the archives. The tragic loss is not confined to the past but continues through time: the stolen children of the 19th Century are the missing generations of today.

Tense Past reconnects our hearts and minds to the consequences of the frontier wars, the missing ancestors and lost generations, and the impact of colonisation on Tasmania’s first people — then and now.

Julie Gough – Tense Past Presented by Dark Mofo and the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart 7 June – 3 November 2019.