Modern understanding of World War I is dominated by the immense human cost of the war on land with its trenches, artillery and machine guns – but the war was won by sea power.

In August 1914 Britain, the greatest naval power of the age, controlled the oceans, cutting Germany off from global resources. Without imported raw materials and food Germany could only fight for a year or two before facing starvation and industrial failure.

To break the crippling blockade, Imperial Germany’s High Seas Fleet had to defeat the British Grand Fleet, based at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, which closed the North Sea to German shipping. Outnumbered and outgunned, it never attempted to do so.

The two fleets met for the only time on May 31 1916, almost two years after the war began, in the largest surface naval battle in history – the Battle of Jutland. The Germans had sailed north, planning to cut off and destroy a fraction of the Grand Fleet. The British, forewarned by radio intelligence, steamed south planning to catch the entire High Seas Fleet.

What happened at Jutland

The fleets met off the western coast of Denmark. The British force of 150 ships, including 37 battleships, was one-third larger than the German fleet.

The action began in the mid-afternoon and involved a series of relatively short artillery and torpedo exchanges which were restricted by poor visibility. Fighting continued until after midnight when the Germans managed to disengage and – after a chaotic night of action – retreat to base.

The battle exposed serious failings in the British Battle Cruiser Fleet, the advanced scouting force of the Grand Fleet, where poor gunnery and signalling practice was compounded by the careless handling of high explosive ammunition, resulting in the destruction of three battleships. By contrast, the Grand Fleet comprehensively outgunned the German battle fleet in two brief gunnery exchanges, forcing the German Admiral Reinhard Scheer into dangerous emergency manoeuvres to turn away from the battle.

Comparisons with Trafalgar

The result of the action has been contested ever since. Both sides measured the action against Nelson’s defeat of the Napoleonic fleet in the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, the ultimate naval victory. The Kaiser declared Jutland had broken “the magic of Trafalgar”, while many in Britain were shocked by the failure to repeat Nelson’s triumph.

These analogies missed the fundamental issue. Both Jutland and Trafalgar maintained Britain’s command of the oceans and the economic blockade, which was its primary strategic weapon.

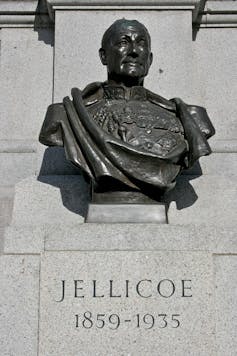

In 1805, Nelson had faced an enemy of markedly inferior skill: at Jutland Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, commander of the Grand Fleet, faced a highly capable and resolute enemy, whose ships and men were equal to his own. He could not afford to take risks in pursuit of a “decisive” victory because, unlike Nelson, he commanded Britain’s only modern battle fleet.

As Winston Churchill famously observed, Jellicoe was the only man on either side “who could have lost the war in an afternoon”. But Jellicoe did not have to win, he had ensure he did not lose – and his cautious professionalism was perfectly suited to the occasion. That said, he did seek try to destroy the enemy, twice outmanoeuvring Scheer and cutting off his route home. With a little luck, and more capable subordinates, Jellicoe might have achieved a truly stunning success – but he would not take excessive risks to secure one.

Having listened to the Kaiser’s bombastic claims of victory, after the battle Scheer decided he would not risk another such encounter. He knew that while German tactical skill and resilience at Jutland had been impressive, it did not amount to strategic success.

Who won?

German propaganda claimed victory, because they had sunk more British ships – six big ships to two – and killed 60% more British sailors; the toll was 6,094 killed and 674 wounded.

These numbers were irrelevant: the British remained on the battlefield the next day, ready to fight, while Scheer had turned and fled on three occasions, limping home with much of his fleet heavily damaged. He did not attempt to engage the Grand Fleet again. This was the real test of victory.

The Grand Fleet anchored a British economic blockade that was slowly strangling the German war effort. Unable to break the blockade, the German High Command resorted to unrestricted submarine warfare, sinking all British and neutral merchant ships within a self-proclaimed “war zone” without making provision for the safety of passengers and crew.

This gross violation of international law brought the United States into the conflict alongside Britain and France in April 1917. This made the economic blockade much tighter, leaving Germany to stake everything on a military victory on the Western Front in the spring of 1918. In October 1918 the High Seas Fleet collapsed in mutiny and helped bring down Germany’s Imperial regime.

Although a library of books and articles have dissected British tactical and technological failings at Jutland – and they were significant – the British won the battle, and that victory settled the outcome of the World War I.