The artist Kwementyaye (Kathleen) Petyarre (c. 1938 – 24 November 2018) has died in Alice Springs, surrounded by family and loved ones, at about the age of 80. Alhwarrpe.

“About” that age, because Petyarre was born out bush, delivered by Anmatyerr midwives at Atnangker on Anmatyerr country in Australia’s northeast Central Desert. Petyarre’s birth was not recorded in any official birth register, although it is believed to have taken place between the late 1930s or early ’40s.

Earliest days

Known in childhood as Kweyetemp Petyarre, she and her extended family group moved around their vast desert estate in Anmatyerr country. Their base was Atnangker, a site over which they exerted proprietary rights through the male line. According to principles of systematic rotational navigation they hunted and gathered food and water on the basis of seasonal availability. Their daily cuisine could include emu, kangaroo, perentie, goanna, blue tongue lizard, witchetty grubs, yams, bush plums, bush tomatoes and bush honey.

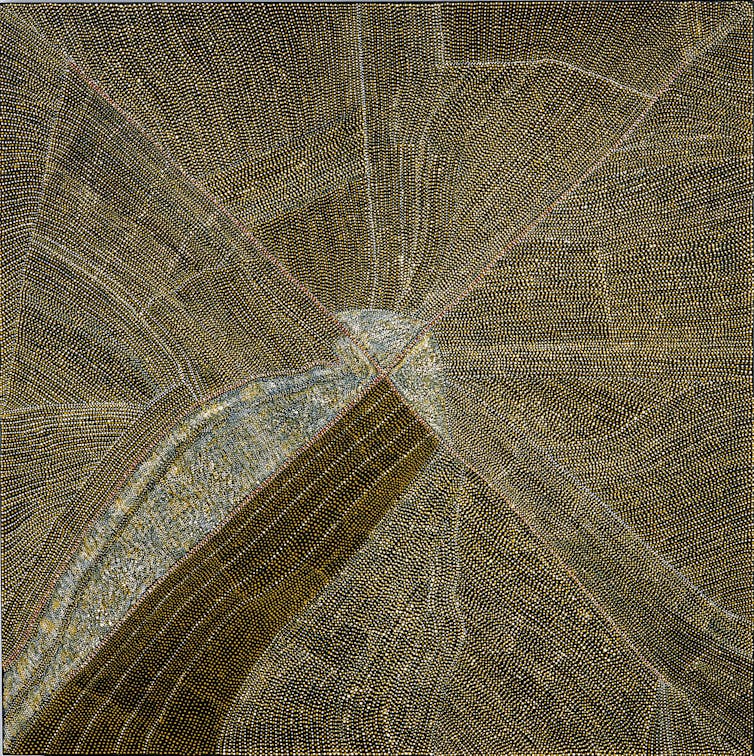

Anmatyerr women would grind seeds and cook delicious cakes on open fires. Later, the “bush seeds” that flourished on her country would become a signature theme in Petyarre’s oeuvre. Delicately represented by abundant tiny dots that she originally applied with a tyepal, fashioned from a twig and also used by women in body painting, later Petyarre turned to miniature saté sticks, sourced from Indonesia.

During her early years, under the instruction of her paternal grandmother, little Kweyetemp embarked on a highly disciplined classical Eastern Anmatyerr education. This was how she acquired foundational knowledge relating to her principal Dreaming Ancestor, Arnkerrth, the Mountain or Thorny Devil.

A small lizard that looks like a bonsai dinosaur, arnkerrth avoids predators by changing colour to camouflage itself to merge with the surrounding environment, also needing only minimal water to survive. Underpinned by Anmatyerr Law, this small creature would become Petyarre’s greatest and most significant artistic subject.

Meeting a white man for the first time

In the late 1940s, after the second world war, Kweyetemp first encountered a white man. The man was crossing Anmatyerr country with a camel. From behind small shrubs, the children peeked nervously at the strangely hued man and his equally bizarre animal companion. Eventually their father revealed himself and addressed the stranger, offering him food and water, which the interloper desperately needed.

With no rancour, Petyarre informed me that the man, who remained there for some time, insisted that the family cover their nakedness. In turn, he supplied “garments”.

Chuckling, Petyarre reflected on this to me in the following words:

We girls had to wear sacks, flour bags with cut-out hole (sic), for neck and arms. Really itchy one!

The older boys were made to wear army supply shorts. This was in the desert summer heat in excess of 50°C in the shade. The uninvited interloper simply would not abide with the family’s nakedness.

Becoming ‘Kathleen’

Not far from Atnangker, a pastoral property on Anmatyerr country had been established by whitefellas some years earlier. The latter group named that large stretch of country – bitterly tongue in cheek – “Utopia”.

This led to Petyarre’s family working for the new “owners” of the pastoral lease. In return the family received rations of flour, sugar and tea, but no pay. Unrelenting assimilatory pressure ensued. English names were imposed on all Eastern Anmatyerr people, and Kweyetemp became “Kathleen”.

A school was set up in a silver bullet caravan and Kathleen began working there as the teacher’s aide, insisting that she instruct the children in their natal language, Eastern Anmatyerr. Her close sister Violet worked in the school as a laundress. Older Anmatyerr ladies were charged to sew uniforms with the words “Utopia School” stitched on.

But apropos of the uniforms, there was a catch. Anmatyerr children were permitted to wear the uniforms during school hours only, and were obliged to remove them before returning home in the afternoon. So they left in the same way they’d arrived at school on the same morning – naked.

Violet would wash their uniforms daily, hanging them out to dry overnight so that in the morning, at school, the children would don clean uniforms. Ironic, given that the small settlements that comprised Utopia had very little running water.

“Utopia” is an umbrella term encompassing a cluster of widely dispersed small homelands, once known as “outstations”. In 1977 Jenny Green arrived in Utopia to work as an adult educator, organising workshops in batik method. For kinship-related reasons, 99% of those who attended those workshops were women. These included Emily Kngwarrey (Kathleen’s aunt), Kathleen, Violet and Gloria and the other four Petyarre sisters.

Rodney Gooch at Utopia

In 1987, Rodney Gooch (1949-2002), a flamboyantly “out” gay man, who had been working for the Central Australia Aboriginal Media Association in Alice Springs, was asked to take over the management of the Utopia Women’s Batik Group. Kathleen wasn’t alone in recollecting that the Eastern Anmatyerr women adored “Ronnie” as they called him.

During his tenure, Gooch introduced acrylic painting on canvas and other media. This was a movement that had started in Papunya in the early ‘70s and took off like wildfire across the arid desert regions.

Kathleen, whose chronic asthmatic condition arose from an allergic reaction to the fumes generated in batik production, took to the new media like a duck to water.

By the mid-1990s Petyarre had become involved with Adelaide’s Gallerie Australis in Adelaide, which represented her exclusively. Exhibitions of her astonishing artworks were mounted – with art lovers attending in droves.

The Telstra prize

This culminated in 1996 when Petyarre won the coveted major prize: the Telstra Art Award.

But this success was relatively short-lived when Petyarre’s non-Indigenous partner Ray Beamish, a former Darwin “long-grasser”, came forward with a claim that he had painted parts of Petyarre’s artworks, including the prizewinning work. A visual art writer working for The Australian newspaper took up this allegation with gusto, which served to amplify the issue. It became national and even international news.

The protracted period of time that it took to resolve this took an enormous toll on Kathleen’s health: she began shaking with fear, for months barely speaking and not painting at all. The source of Petyarre’s malaise was what she understood to be the theft of the Mountain Devil Dreaming, passed down to her by generations of Ancestors who held sacred copyright over that Dreaming.

In 1997-1998, the Board of the Museum and Art Gallery of the NT conducted an enquiry into these allegations. After strenuous investigations and interviews with relevant parties, Board Chair Colin McDonald announced that:

The Board found the allegations of Mr Beamish regarding the authorship of the painting were not proved. Accordingly, there is not basis for interfering with the decision of the judges awarding the 1996 Telstra Prize to Kathleen Petyarre. (24 April 1998).

Fortunately Petyarre eventually returned to painting, and since then her work has been exhibited worldwide – including France, Scotland, Indonesia and the United States. In many instances she travelled to those destinations. Like her Ancestor Arnkerrth, the Old Woman Mountain Devil, Petyarre became a seasoned journeywoman.

Wicked humour

In relation to her personal qualities Kathleen could be imperious, but the attribute I best remember is her marvellous, often wicked, sense of humour. When in 1998 I travelled to the US with Kathleen and her sister Violet, this came to the fore. There was an international conference for Indigenous people worldwide that we attended. The three of us stayed in the same hotel room.

One example will suffice. The background to this is that while Kathleen’s understanding of English was very good, her spoken English was so inflected with Anmatyerr language that 99% of English speakers found it unintelligible. It also practically stopped Kathleen and Violet from trying to communicate verbally, although neither is shy.

As a result, all the other conference attendees addressed me as the conduit to the two Anmatyerr women. A very earnest, middle-aged American lady in hippy attire approached me in the presence of the sisters, asking me, “Is it true that they only communicate by telepathy”?

Kathleen remained silent, but using only her hands she gestured towards her mouth in mock-sign language. Hence I responded to the lady by saying, “No, that isn’t true. Of course they talk.” When we returned to our hotel room that evening, all three of us acted out this scenario over and over again, shrieking and screaming with laughter. It must be admitted that our outbreak of unstoppable hilarity was underpropped by a teeny modicum of schadenfreude.

The Old Mountain Devil Woman

The thorny devil is unable to cover country in a straight line – she always takes a semi-circular route across her vast, arid country. This seems an apt metaphor for Kweyetemp Petyarre’s life, which hasn’t followed the trajectory that her younger self had foreseen, perforce veering off and rounding corners that she had never dreamed of in her childhood. That life, so rudely interrupted by the colonisers, was largely held together by her love of her family, and their love for her.

Petyarre also enjoyed being feted as a successful artist, and the travel that involved – arnkerrth is a great traveller.

On the occasion that I interviewed Petyarre on the subject of death, she had this to say:

If I could make wish I like to move straight back into them old days out in spinifex country—good. Life good then — all the time.

The author has received permission from the family to use Kathleen Petyarre’s full name and images of her in this article.