Kenneth Branagh’s new adaptation of Death on the Nile arrives with a lot of preconceived baggage. We know Agatha Christie. We know Poirot.

Christie’s influence on the murder mystery genre cannot be overstated. Her stories feature heavily in the contemporary media landscape; reruns of various incarnations regularly appear in television schedules. David Suchet’s portrayal of her detective Hercule Poirot is iconic – as are Julia McKenzie, Geraldine McEwan and Joan Hickson as Miss Marple.

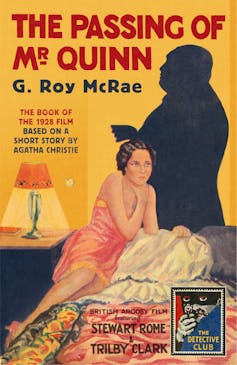

The author of 66 detective novels, 14 short story collections and six bittersweet romance novels under the pseudonym Mary Westmacott, Christie has sold over two billion books. The first film adaptation of her work was The Passing of Mr Quinn in 1928. Her mysteries have been a staple of the big and small screen ever since.

Key to the Agatha Christie narrative – on screen and on the page – is the puzzle. The murder mystery is ultimately a game where you have to guess the killer before the detective does.

For many fans of Christie, adaptations are judged according to the degree to which they conform to their source text. How close is the adaptation to Christie’s original puzzle? Do the clues “fit together” in a similar fashion?

Reactions to Branagh’s adaptations of Christie complicate this picture even further. We aren’t just comparing these films to the novels themselves but other screen adaptations – the portrayals of Poirot we are more accustomed to.

Past Poirots

David Suchet is known as the quintessential Poirot, having played the role on television from 1989 to 2013. Suchet is faithful to Christie’s description of Poirot in her writing and fantastic in portraying Poirot’s iconic “rapid, mincing gait” and particular mannerisms.

This is Branagh’s second performance as Poirot. In 2017’s Murder on the Orient Express, the importance of the clues given by the suspects in the interviews became secondary to Branagh’s own peculiar portrayal of Poirot.

Branagh’s adaptations are more concerned with Poirot himself than any of the suspects.

The method of the crime in Death on the Nile, the puzzle Poirot (and we) must solve, is very intricate. It is one of Christie’s best in my opinion. In Branagh’s film, the central murder happens far too late in the narrative: the murder happening 70 minutes into a two hour film leaves insufficient time for the investigation.

What I love about the books and many of the adaptations, particularly Suchet’s versions, is how each clue is slowly considered.

How do we interpret each clue? What are its implications? This is where having an assistant for Poirot to bounce ideas off (and to show off as well) comes in handy. In the book of Death on the Nile it is Colonel Race. In this film, Poirot doesn’t really engage with anyone in any meaningful manner.

Rather than just a mystery, this film functions more as an exploratory narrative into Poirot. We get an absurd origin story for his moustache. We learn of his lost love. This theme about the extremities heartbreak can drive us to permeates throughout all the suspects.

It is an interesting narrative device but, in the end, it is still all about Poirot. There is no care given to these suspects or the importance of several clues.

But the biggest crime with Branagh’s portrayal of Poirot is the lack of charm. While the Poirot audiences are used to is peculiar, pompous and obsessed with order, he is above all else charming. He gets to know each suspect, asks them seemingly irrelevant questions and makes them lower their guard.

In this version he is gruff, unfriendly and often mean.

Read more: Poirot at 100: the refugee detective who stole Britain's heart

Death of the author

As with Murder on the Orient Express, Branagh again has the film veer into absurd action sequences. These moments break the narrative tone. The Poirot we are accustomed to does not chase suspects as if he was an action hero.

The visual effects are notably poor. The green screen is laughable at times. With the exception of a wonderful scene in Rameses II’s tomb, there is no genuine sense of place. There is no depth given to Egypt here.

There is so much potential to this film. The cast is superb and harks back to the incredible cast of the 1978 version, which featured Maggie Smith, Bette Davis, Mia Farrow, Angela Lansbury and Jane Birkin.

The Murder on the Orient Express performed well at the box office but received mixed critical reviews. The negative response was centred largely around the notion of fidelity. As the Atlantic described it, the film was “self-indulgent and thoroughly unnecessary”.

Branagh’s adaptation of Death on the Nile has been met with an equal amount of trepidation. The adapted work can never fully forget the original source.

It is interesting, then, that Christie’s name isn’t as present on the promotional material for Death on the Nile as, say, the BBC’s recent collection of miniseries adapted by Sarah Phelps.

Perhaps this is to signal Christie is no longer the sole author of this mystery, or maybe we are supposed to believe this version of Christie is elevated above the quaint, televisual fare that we may be accustomed to.

Fidelity informs the critical responses of Agatha Christie fans to adaptations of her work because, as film academic Christine Geraghty argues, “faithfulness matters when it matters to the viewer”.

Branagh’s adaptations of Christie are for an audience that haven’t read the original book and don’t already adore Suchet’s portrayal of Poirot. This film is for a new audience: an audience which isn’t hoping for fidelity.

If many go on to read her work and watch the rich history of Agatha Christie screen adaptations, that can only be a good thing – it gets a lot better than this attempt.

Read more: Death on the Nile: a meditation on celebrity and a riposte to Christie's critics