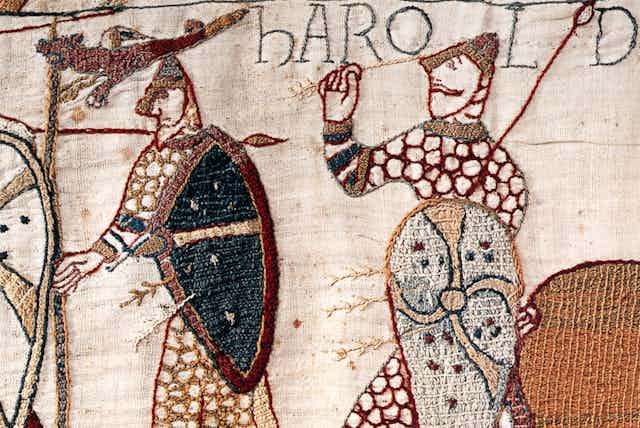

We may not know exactly how England’s King Harold died at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 – was he cut down by swords or was it that fateful arrow? – but die he certainly did, in spite of fanciful later rumours that he fled and became a hermit. But what if it had been Duke William’s lifeless body stretched out on English soil, not Harold’s? History would obviously have been very different – but not necessarily in the ways that might seem obvious.

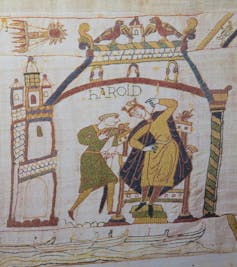

Harold’s ascent to the English throne as Harold II had taken place just a few months before he met his fate. But his coronation in January 1066 was the result of years of careful planning that put him in pole position on King Edward the Confessor’s death, even though he was not related by blood.

Yet the new king had hardly begun to enjoy the fruits of his strategems when he was faced by enemy invasion: the seasoned Viking warrior Harald Hardrada landed in the north, marching in collaboration with Harold’s rebel brother Tostig. No sooner had Harold won a stunning victory at Stamford Bridge, which left both Hardrada and Tostig dead, than news reached the English king of a second invasion, this time in the south, by the Norman Duke William “the Bastard”. Harold raced from Yorkshire to Sussex to meet the challenge and the armies clashed at a site known to this day as Battle.

William’s defeat, and death, was certainly a plausible outcome of his invasion. After all, Hastings was an unusually long-lasting and hard-fought battle. Our sources give the impression of two evenly-matched armies, each composed of several thousand soldiers, and of a whole day’s fighting that inflicted heavy casualties on both sides.

Historians have made much of the Normans’ supposed military advantages – notably their use of sophisticated cavalry tactics – but Harold was an experienced general commanding battle-hardened soldiers. And unlike William, he could have expected reinforcements had he only managed to make it through to evening, as further Saxon troops arrived from Yorkshire.

The Norman duke, on the other hand, was at the end of a very long and uncertain supply chain, isolated in hostile territory. Anything less than a knockout blow at Hastings could have been fatal to his plans, and perhaps to him, too.

On the cusp of glory

Had Harold survived and won, he would probably be celebrated today as one of England’s greatest warrior kings, on a par with Richard Lionheart and Edward I, and indeed Æthelstan – we would probably pay much more attention to the earlier English kings without the artificial break provided by the Conquest. He would have defeated mighty enemies in pitched battles at opposite ends of the country within weeks of each other: quite a feat. Indeed, we might well be talking of King Harold the Great, and perhaps of the great dynasty of the Godwinsons.

And yet we might know much less about the England that Harold would have ruled. After all, the single greatest store of information about 11th-century England, Domesday Book, was a conqueror’s book, made to record the victor’s winnings, and preserved as a powerful symbol of that conquest. Without Domesday Book, which has no serious parallel in continental evidence at this date, many English villages and towns could have languished in obscurity for another century or longer.

So Harold’s England would be less visible to historians. If, of course, an England had survived to be ruled over at all. One of the most striking characteristics of pre-Conquest England are its deep political divisions. It was these divisions that had paved the way for Harald Hardrada’s invasion in the north, allied with powerful English rebels including Tostig – and it was these divisions that had created the circumstances for William’s invasion, too, ultimately a byproduct of the rivalry between Harold’s family and King Edward the Confessor.

King Harold II after Hastings would have been rich, but he would still have faced dangerous enemies and rivals – not least the young Edgar. Edgar’s family claim to the throne – he was the grandson of the earlier king, Edmund II Ironside, and so a direct descendant of Alfred the Great – was far stronger than Harold’s. There would have been more crises to come after Hastings.

One of the merits of counterfactual history is to remind us that things could have been different: it challenges our assumptions and prejudices. Now, the thriving of medieval England seems obvious, but at the time of the conquest, contemporary France had torn itself apart in what has become known as the Feudal Revolution.

A similar fate could have awaited an English king after the shortlived triumphs of 1066: civil war, fragmentation, and the localisation of power. King William, by contrast, had a blank slate and could start (almost) from scratch, creating a new aristocracy that owed everything to him. So it’s not the least of the ironies of William’s Norman Conquest that it perhaps helped to save the country that it also brought to its knees.