“ADHD”, “disruptive”, “behavioural difficulties”: labels like these are applied daily to our children. But there is a growing concern amongst educators, parents and pupils that the use of such labels has the potential to damage young lives.

What’s in a label?

The labels we use to categorise children can be medical, such as “ADHD” (Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) and “ODD” (Oppositional defiant disorder). They can be administrative, like “social, emotional and behavioural difficulties”, and they can be informal (“challenging” or “disruptive”).

Labels like these are used in our education system to categorise children according to their academic ability, educational needs and behaviour. The use of formal labels can help identify children who require additional support. But the use of labelling remains controversial.

Debates about the existence of disorders such as ADHD are ongoing. Research has repeatedly shown that children from minority groups are more likely to be labelled as having a behavioural disorder than their peers. Clearly not all labels are created equally. Whether a child is formally or informally labelled as “mad, bad or sad” can determine the kind of support (or punishment) they receive.

Labels are harming our children

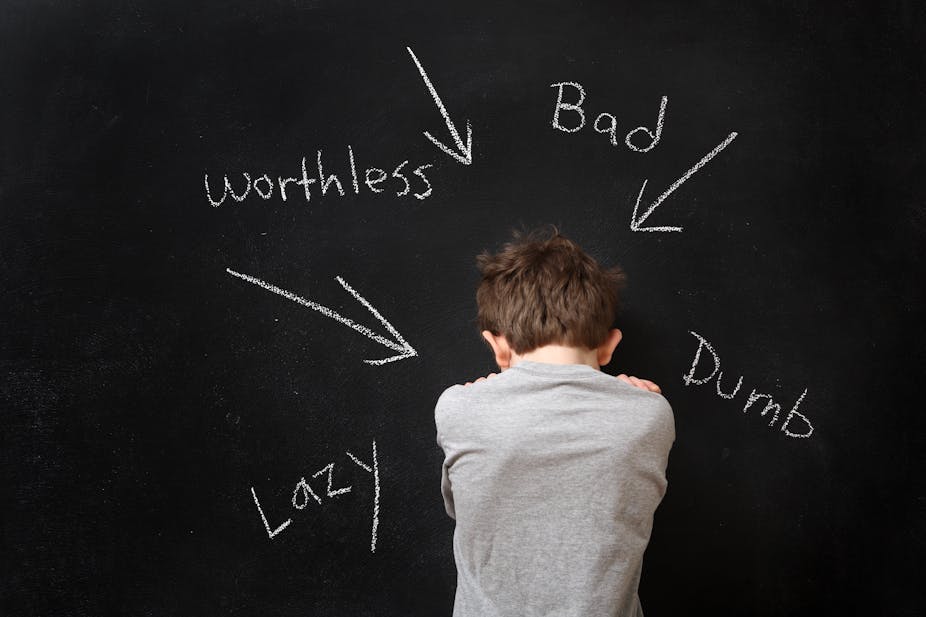

The use of labels can be harmful to children. The relationship between labelling and stigmatisation, although complex, is well established. Being labelled as “different” can lead to bullying and marginalisation in schools.

Children change and develop but labels, unfortunately, tend to stick. This can make it hard for children to leave behind negative reputations and start afresh. Many labels, such as “social, emotional and behavioural difficulties”, locate the problem within the child, individualising issues and shifting the focus away from the wider context. This can make it hard to tackle problems holistically.

Labels that focus on the difficulties a child is having do so at the expense of recognising their capabilities and strengths in other areas. Such labels can be very difficult to see past, even though they are only one part of a child’s identity. This can result in lowering adults’ expectations of children and unduly influencing their interpretation of a child’s actions.

Labels can help

Not all uses of labels have negative consequences for children. Labels, such as “ADHD”, can act as “labels of forgiveness” relieving parents and children of guilt and blame and increasing the tolerance of teachers. Labels can also be used to bring together children with similar experiences and foster a positive group identity where peers provide support for children and their families.

Medical and administrative labels can open the door to extra resources so children get the help they need, such as additional assistance in the classroom or access to counselling. Labels, where a shared understanding exists, can facilitate inter-professional working for the benefit of the child. They can also help educators identify necessary professional development opportunities and implement appropriate inclusive teaching strategies.

We need to listen to students

We can see that the use of labels is a double-edged sword that can have both a positive and negative impact on young lives. So how do parents and educators negotiate this minefield to know when labels are helpful and when they are harmful?

In order to learn when and how to use labels for the best interests of the child, we need to know more about the experiences and outcomes of labelled children.

Listening to students is critical in this process and needs to happen more. This can be as simple as asking children directly about their experience of the labelling process.

What kind of labelling do they find helpful or harmful? How can we create spaces for the labelling process to be challenged by young people? Can students take a more active role in developing their own educational plans?

Students have a right to be involved in decisions that impact their education. Research with girls and boys identified as having behavioural difficulties has shown that they value having their views on schooling listened to.

It has also shown that “labelled” students can offer important insights into their education - including their experience of being labelled, what they see as the causes of their behaviour and what needs to change in schools to improve their learning.

For all this to work, we need to be willing to learn from students and to see them as capable of identifying their own educational needs (and labels) in partnership with professionals and parents. Educators may need support to develop the skills necessary to facilitate this kind of participation and to change established ways of doing things.

Listening to students who have been, or who are at risk of being labelled can also support the kinds of relationships that encourage teachers to see beyond labels, empower students and help protect against some of the potential harms of labelling.