It’s a pandemic within the pandemic. Across Latin America, gender-based violence has spiked since COVID-19 broke out.

Almost 1,200 women disappeared in Peru between March 11 and June 30, the Ministry of Women reported. In Brazil, 143 women in 12 states were murdered in March and April – a 22% increase over the same period in 2019.

Reports of rape, murder and domestic violence are also way up in Mexico. In Guatemala, they’re down significantly – a likely sign that women are too afraid to call the police on the partners they’re locked down with.

The pandemic worsened but did not create this problem: Latin America has long been among the world’s deadliest places to be a woman.

Don’t blame ‘machismo’

I have spent three decades studying gendered violence as well as women’s organizing in Latin America, an increasingly vocal and potent social force.

Though patriarchy is part of the problem, Latin America’s gender violence cannot simply be attributed to “machismo.” Nor is gender inequality particularly extreme there. Education levels among Latin American women and girls have been rising for decades and – unlike the U.S. – many countries have quotas for women to hold political office. Several have elected women presidents.

My research, which often centers on Indigenous communities, traces violence against women in Latin America instead to both the region’s colonial history and to a complex web of social, racial, gender and economic inequalities.

I’ll use Guatemala, a country I know well, as a case study to unravel this thread. But we could engage in a similar exercise with other Latin American countries or the U.S., where violence against women is a pervasive, historically rooted problem, too – and one that disproportionately affects women of color.

In Guatemala, where 600 to 700 women are killed every year, gendered violence has deep roots. Mass rape carried out during massacres was a tool of systematic, generalized terror during the country’s 36-year civil war, when citizens and armed insurgencies rose up against the government. The war, which ended in 1996, killed over 200,000 Guatemalans.

Mass rape has been used as a weapon of war in many conflicts. In Guatemala, government forces targeted Indigenous women. While Guatemala’s Indigenous population is between 44% and 60% Indigenous, based on the census and other demographic data, about 90% of the over 100,000 women raped during the war were Indigenous Mayans.

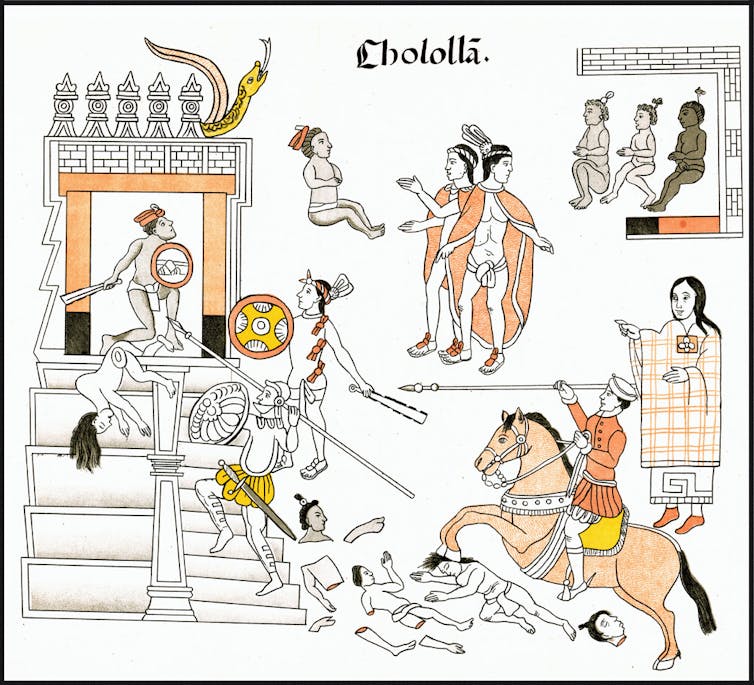

Testimonies from the war demonstrate that soldiers saw Indigenous women as having little humanity. They knew Mayan women could be raped, killed and mutilated with impunity. This is a legacy of Spanish colonialism. Starting in the 16th century, Indigenous peoples and Afro-descendants across the Americas were enslaved or compelled into forced labor by the Spanish, treated as private property, often brutally.

Some Black and Indigenous women actually tried to fight their ill treatment in court during the colonial period, but they had fewer legal rights than white Spanish conquerors and their descendants. The subjugation and marginalization of Black and Indigenous Latin Americans continues into the present day.

Internalized oppression

In Guatemala, violence against women affects Indigenous women disproportionately, but not exclusively. Conservative Catholic and evangelical moral teachings hold that women should be chaste and obey their husbands, creating the idea that men can control the women with whom they are in a sexual relationship.

In a 2014 survey published by the Latin American Public Opinion Project at Vanderbilt University, Guatemalans were more accepting of gender violence than any other Latin Americans, with 58% of respondents saying suspected infidelity justified physical abuse.

Women as well as men have internalized this view. During my research in Guatemala and Mexico, many women shared stories about how their own mothers, mother-in-law or neighbors told them to “aguantar” – put up with – their husbands’ abuse, saying it was a man’s right to punish bad wives.

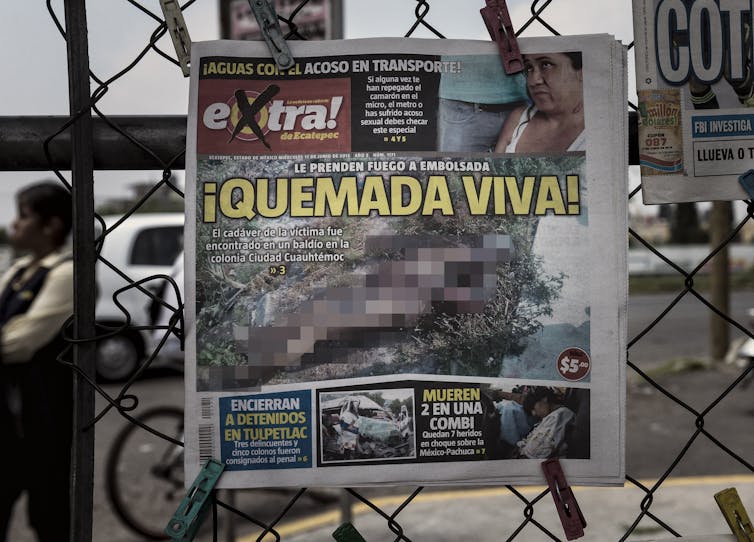

The media, police and often even official justice systems reinforce strict constraints on women’s behavior. When women are murdered in Guatemala and Mexico – a daily occurrence – headlines often read, “Man Kills His Wife Because of Jealousy.” In court and online, rape survivors are still accused of “asking for it” if they were assaulted while out without male supervision.

How to protect women

Latin American countries have made many creative, serious efforts to protect women.

Seventeen have passed laws making feminicide – the intentional killing of women or girls because they are female – its own crime separate from homicide, with long mandatory prison sentences to try to deter this. Many countries have also created women-only police stations , produced statistical data on feminicide, improved reporting avenues for gendered violence and funded more women’s shelters.

Guatemala even created special courts where men accused of gender violence – whether feminicide, sexual assault or psychological violence – are tried.

Research I conducted with my colleague, political scientist Erin Beck, finds that these specialized courts have been important in recognizing violence against women as a serious crime, punishing it and providing victims with much-needed legal, social and psychological support. But we also found critical limitations related to insufficient funding, staff burnout and weak investigations.

There is also an enormous linguistic and cultural gap between judicial officials and in many parts of the country the largely Indigenous, non-Spanish-speaking women they serve. Many of these women are so poor and geographically isolated they can’t even make it into court, leaving flight as their only option of escaping violence.

The collective body

All these efforts to protect women – whether in Guatemala, elsewhere in Latin America or the U.S. – are narrow and legalistic. They make feminicide one crime, physical assault a different crime, and rape another – and attempt to indict and punish men for those acts.

But they fail to indict the broader systems that perpetuate these problems, like social, racial, and economic inequalities, family relationships and social mores.

Some Indigenous women’s groups say gendered violence is a collective problem that needs collective solutions.

“When they rape, disappear, jail or assassinate a woman, it is as if all the community, the neighborhood, the community or the family has been raped,” said the Mexican Indigenous activist Marichuy at a rally in Mexico City in 2017.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

In Marichuy’s analysis, violence against one Indigenous woman is the result of an entire society that dehumanizes her people. So simply sending the abuser to prison is not sufficient. Gendered violence calls for a punishment that both implicates the community and the offender – and tries to heal them.

Some Mexican Indigenous communities have autonomous police and justice systems, which use discussion and mediation to reach a verdict and emphasize reconciliation over punishment. Sentences of community service – whether construction, digging drainage or other manual labor – serve to both punish and socially reintegrate offenders. Terms range from a few weeks for simple theft to eight years for murder.

Stopping gendered violence in Latin America, the U.S. or anywhere will be a complicated, long-term process. And grand social progress seems unlikely in a pandemic. But when lockdowns end, restorative justice seems like a good way to start helping women and our communities.