When the impact of the coronavirus first hit the UK, I stared at the empty rows in my local supermarket, cleared as a result of people stockpiling goods. I had read about “panic buying” in other countries but was not prepared for the scenes that greeted me. The bare shelves were a constant reminder of how fearful people were about the impact of COVID-19, lockdown and about feeding themselves and their families while being sequestered at home. My first thought was of a biblical locust plague; it was as if a swarm of locusts had worked their way through the store, clearing out all the family basics – flour, pasta, bread, toilet rolls and other essential staples.

More visible, tangible reminders of the coronavirus pandemic were the hand sanitiser stations, the new experience of wearing masks out in public and social distancing – the “hands, face and space” mantra that the UK government had adopted. This was our social obligation and responsibility in fighting this virus, by reducing transmission rates and hospital admissions.

Standing in a queue for goods with my 13-year-old son, as customers were being counted in and out, he remarked on the line stretching across the car park, the spacing enforced by staff, the sanitised baskets and trolleys and the face masks on everyone waiting. He asked if I had ever seen anything like this before. I told him no I had not, and I hoped I never would again. While the sanitising and face masks were seen as essential and enforced, staff in retail environments struggled to get access to personal protective equipment (PPE), a problem that also became apparent for frontline healthcare staff in hospitals and care workers in homes for the elderly. Staff shortages across sectors came from the reduced availability of PPE but also because of workers having to self-isolate.

Concerns over access to food and general supplies were endemic and similar fears existed about access to healthcare and whether hospitals would have enough staff and equipment – PPE, medicines, ventilators, oxygen and vaccines – to treat patients with COVID-19, not to mention other urgent medical issues. In India more recently, oxygen shortages ravaged the care that emergency departments were able to give to COVID patients and critical care beds were limited. Pop-up isolation wards were created in train carriages as hospitals ran out of capacity to treat patients.

I study supply chains and health operations and have never experienced such a phenomenon as seen in 2020-21. And as one of the biggest vaccination drives in history rolls out globally, there are ongoing fears about vaccine supplies. The vaccination programme has been hailed as the way out of the pandemic, getting societies and economies back to where they once were. The demand within such a short time frame is unprecedented.

Supply chain disruptions

Supply chain disruptions that lead to restricted access to products have happened before, but how we learn from these and how practice changes accordingly is a matter of debate.

I was a supply chain manager in a pharmacy in a large teaching hospital back in the early 2000s, and the recall of products from quality issues and medicine shortages was commonplace. We would receive alerts from regional and national bodies and take action to find affected stock to return or contact suppliers for additional stock. The systems were in place to accommodate this successfully.

Fast forward to 2020, the same practice is in place but other factors have exacerbated the frequency and magnitude of these issues. The globalisation of supply chains, the growth of pharmaceutical companies in this sector, the explosion of the generics market (where products are no longer patented and can be reproduced by other companies) offering high-volume low-cost medicines such as paracetamol, have increased complexity in the pharmaceutical supply chain. Added to this are new trading agreements (eg Brexit), the grounding of the Ever Given ship in the Suez Canal (which delayed supplies) and of course the pandemic. So many high-risk and high-impact events all occurring within one year, have caused chaos with medicines supplies and associated equipment.

Problems within supply chains are endemic, with capacity struggling to match product demand. The pandemic has affected all supply chains so we have seen large scale shortages of key items which are vital to business, including medicines, semi-conductors for computers and electronic devices, wood and clothing. In the US, the erosion of “industrial commons” – domestic capabilities needed to produce goods for home use – was cited as a cause of supply chain deficiencies. The US invoked the Defense Production Act to boost and retain domestic vaccine production to support the country’s own COVID-19 vaccine rollout.

Lean manufacturing principles and “just in time” practices adopted by manufacturers – buying products to be delivered just in time for production to reduce stockholding – left companies with limited stocks to respond to increasing demand, and no toilet rolls on supermarket shelves. In hospitals and other healthcare operations, stockholding capacity is dictated by storage facilities, which can be limited, and a reliance on multiple daily deliveries to keep up stock levels. This does not cause problems if there is fairly stable product demand. The pandemic, however, caused a huge surge in global demand for many healthcare products which resulted in widespread product shortages.

Practices which for decades were seen as sensible: avoiding assets being tied up in stock or high levels of waste being generated, are not now effective in the current climate. Coupled with extensive globalisation, longer supply chains spanning multiple parties and countries have increased vulnerability.

Read more: Coronavirus: The perils of our ‘just enough, just in time’ food system

The question must be asked about what we have learned from other epidemics, pandemics and vaccination programmes. From a medical perspective, key lessons relate to science, communication, co-operation and ethics. Understanding when information needs to be shared (when, how and by whom) and the evidence base which supports this, working in partnerships (politicians, public health officials, physicians, scientists and the media) to facilitate this and conducting this process in the most ethical manner.

Increased demand for PPE in the UK was predicted in Exercise Cygnus but recommendations were not deployed at the start of the pandemic. Exercise Cygnus, was a simulation of a flu outbreak at peak, carried out to war-game the UK’s pandemic readiness in 2016. The findings of the exercise indicated that the country was not sufficiently prepared to cope with the extreme demands of a pandemic. Key areas of concern included a lack of joint tactical-level plans and social care provision. The report listed four areas of “key learning” and 22 further “lessons identified” from the exercise, couched as recommendations to government. The creation of stockpiles of PPE and respirators were mentioned.

The output of Exercise Cygnus should have been the blueprint that would dictate the UK’s COVID-19 pandemic response. Unfortunately, the lessons weren’t taken on and just four years later disaster struck.

A question of access

I knew that there were substantial issues in the pharmaceutical supply chain when I visited a retail pharmacy in December 2019 and there was no paracetamol available. Paracetamol is a very cheap product, made in high volume as a generic item, and readily available. The same issue emerged in March 2020 when paracetamol stocks were being readily snapped up to self-medicate COVID symptoms.

Supplies of medicines and vaccines during the pandemic have been problematic. Panic buying of essential products created a surge in demand leading to a pull on manufacturing capacity. A change in consumer behaviours also led to opportunistic criminal behaviour such as the manufacturing of fake COVID vaccines.

Concerns were raised as to the impact of PPE shortage on healthcare workers and possible deaths attributed to lack of it. Questions were also asked about why local PPE manufacturers were not offered contracts and why poor quality products were ordered and received.

In an attempt to protect its home population, India took steps in 2020 to ban exports of some medicines used to manage COVID-19 symptoms, for example paracetamol and the antiviral drug remdesivir. As India is a large exporter of pharmaceuticals the impact of this decision was substantial. In the UK, supermarket and pharmacy shelves went bare and any stock that was available was substantially higher in cost, up to 30% in some cases for paracetamol, aspirin and ibuprofen.

Much of the world is heavily reliant on manufacturing countries such as India and China for pharmaceutical products. These are fragile points in a global supply chain that fractured under the impact of the pandemic. India is often described as the world’s pharma capital, where inexpensive, quality drugs are readily available. Despite this and the volume of vaccines also produced in India, the country has still struggled with its own escalating COVID cases.

Coupled with shortages in staff and mandated closures of manufacturing sites to reduce the risk of transmission, and ongoing issues around access to stock and logistics, India and China struggled to respond to product demand. This in itself led to repercussions in wider global supply chains, with demand shifting elsewhere or supplies going unfulfilled.

Vaccine supply chains are challenging based on the complexity of the product, distribution, geography, responsiveness and prioritisation of supplies. This is a fact that underpins decision making when creating vaccines, designing vaccination programmes and allocating supplies. The response to COVID-19 was to create up to 12 billion vaccines by the end of 2021, building on previous capability, but with the added challenge of creating a working vaccine – as vaccines were not quickly created for previous coronavirus strains.

The race for a vaccine

This mammoth task was achievable because of significant governmental intervention and investment in research and development and manufacturing facilities. In the UK, targeted investment in the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine development reaped dividends, accompanied by proactive contract negotiation for eight vaccine candidates.

Rapid vaccine creation for seasonal flu meant when the coronavirus hit, vaccine development happened faster. The process of vaccine creation can take up to ten years but once the coronavirus gene sequencing was complete vaccine creation could commence. The AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine took about ten months to launch.

Some epidemics recur year after year because the affected populations do not have access to appropriate vaccines and drugs. Diseases like COVID-19 do not respect borders. The case is therefore made for equitable access to vaccines and medicines to prevent increasing global transmission rates.

Countries with access to vaccines (through contracts or with the ability to produce them locally) have shown a preponderance to vaccine hoarding, nationalism and protectionism, limiting exports with the aim of protecting their own populations or to fulfil specific contracts. COVAX is the global mechanism for equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines but the initiative has been less successful than expected in securing only 0.3% of vaccines for lower income countries, 75% of which were administered in only ten countries.

Vaccine equity is a contentious issue. Leading up to the G7 summit in June 2021, the UK announced a donation of 100 million surplus vaccines to COVAX and other countries.

Innovations in a time of crisis

Access to PPE, ventilators, oxygen and other equipment needed by frontline staff for patients caused huge problems to healthcare staff across the world, exposing them to risk while delivering care. The demand for PPE was such that it created a global shortage that needed a quick solution. In 2020-21 there was a huge surge in PPE creation. Initially the focus was on safety and functionality but later this shifted to a longer term, sustainability focus and more recently to more security and protection designed into protective equipment.

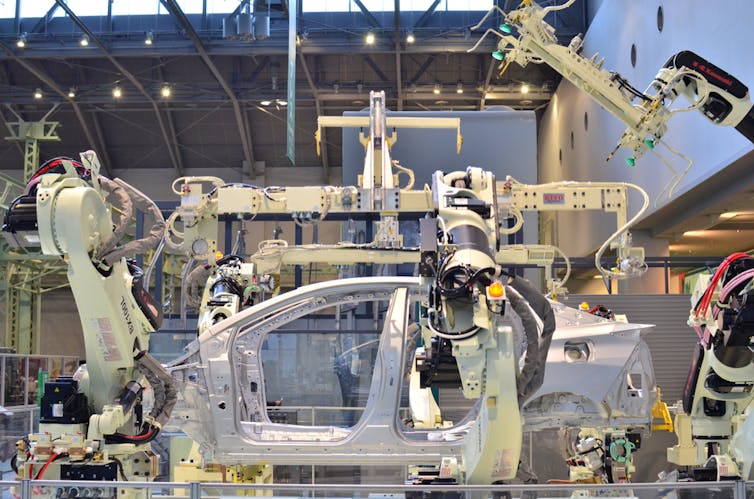

The rush to source and manufacture more technical items such as ventilators has created new partnerships and high levels of innovation. In the Ventilator Challenge UK, a consortium of significant UK industrial, technology and engineering businesses from across the aerospace, automotive and medical sectors, came together to produce medical ventilators.

Some organisations responded to the urgency of product outages. Companies which had never produced medical or healthcare products re-engineered their production processes to do so. Brewdog, a beer manufacturer, showed how some businesses adapted at this time by turning its hand to making hand sanitiser.

The innovation, creativity and educated risk taking that saw some countries get ahead with vaccines were problematic for the European Union, which subsequently suffered delays to their own supplies – a situation that led to political acrimony between the UK and the EU. Concerns about the pace of their vaccination campaign led the EU to demand that the UK export AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccines to support their vaccination campaign and the UK refused to do so. Meanwhile, frustration with the EU’s handling of vaccine procurement led some member countries to decide to secure vaccines direct from manufacturers.

But while the UK and other governments confidently reported on the vaccines they’d secured and their volumes, there was little transparency as to delivery schedules. The upgrading of manufacturing sites to respond to greater demand for vaccines led to production and delivery delays in Moderna, AstraZeneca/Oxford and Pfizer/BioNTech stock in early 2021.

The strategic locating of split-site production facilities – vaccines being produced on multiple sites – can reduce the risk of process contamination or other issues and increase supply chain resilience. AstraZeneca chose to spread its production risk widely, with contracted manufacturing capacity for 2.9 billion vaccine doses to 25 firms in 15 countries. Although in one factory in the US used by two different vaccine firms, production was halted after cross-contamination concerns.

When a pandemic hits, other materials, such as glass vials, tubing, and plastic bags, also become vital. With enhanced production of medicines and equipment comes the increased need to have storage receptacles and packing. The US also invoked legislation to withhold vital materials for domestic production, which was said to contribute to this shortage, but this was lifted in June 2021. Another choke point in the system, the fill and finish section, where the vaccine liquid is placed into vials and packaged for distribution, was recently boosted by companies who make injectables which should increase output volumes.

What we must now do

Moving forward, there are key areas of concern that we should focus on in our supply chains to promote greater stability and access to critical supplies.

Go back to basics. At the height of the pandemic, rapid response was the order of the day. Having rushed to cope and adapt in the face of the pandemic, to keep businesses afloat, we now need to take stock of what businesses and supply chains look like. Changes made to strategies, practice and suppliers, the introduction of new technologies and ad hoc workforce configuration may not suitable as permanent solutions. Now is the time to review and redesign processes and systems.

Businesses can assess the products they buy and where in the world they are created and simulate scenarios of disruptions to identify and fix weak spots in their supply chains. This would inform products that should be stockpiled (due to scarcity or location) and those that can be accessed locally, so lower stock levels can be held or stock delivered just in time for use. The rapid creation of vaccines is a timely reminder of the importance of healthcare research and the production of pharmaceuticals. Investment in the pharmaceutical industry and research funding is essential to increase pandemic preparedness.

Be prepared to be bold and take risks. The pandemic has changed our lives, ways of working and ways of being. What worked before may not work now. We have shown high levels of resilience in being innovative, seeking out novel solutions, designing new technologies, engaging new suppliers to remove choke points and “pivoting” to redesign supply chains. For example, Unilever chose to prioritise the production of its packaged food, surface cleaners, and personal hygiene product brands, in response to heightened demand. Knowing risk hotspots and mitigating these are critical to business survival.

Supply chain configuration. The globalisation of supply chains is something that organisations have strived towards, to offer new business opportunities, greater responsiveness and maximum global presence. This came back to haunt companies during the pandemic, highlighting weaknesses and fractures that enhanced vulnerabilities. Going global, staying local, nearshoring manufacture and shortening supply chains which create domestic vaccine production capability should be debated as businesses learn from this pandemic. PPE sourcing was a critical issue during the pandemic and local sourcing proved essential.

New and existing alliances. The pandemic years 2020-21 offered great insight into business partnerships. Relationships were greatly tested and not all survived. Knowing why age-old relationships failed and new ones never got off the ground is a very salient lesson. Recognising the value of being creative with new partnerships, reducing the focus on costs as the basis for trading and seeking to work smarter are also takeaways from surviving the pandemic. Alliances formed to advance vaccine manufacturing and fill and finish (Sanofi, Merck, GSK, Pfizer) were excellent examples of collaboration.

Build system resilience. The pandemic has impacted all aspects of society. To face future pandemics and large-scale supply chain disruptions we need to be stronger, more resilient and more agile. This relies heavily on enhancements in manufacturing, research intelligence, education, system infrastructure and technologies. It also relies on learning from previous pandemics and epidemics to increase our preparedness for emergency response.

Learn from other supply chains. Vaccine and medicines supply chains are complex, from product creation through to administration to patients. Issues raised in this supply chain such as communication, risk identification and longer supply chains are generic and equally applicable to other supply chains across sectors. What we can learn from other supply chains are their response mechanisms, adaptations and levels of agility. Humanitarian logistics and perishable goods supply chains offer valuable insights. We can determine if such practice can be transferred to the pharmaceutical supply chain. While Amazon may be the distributor of medicines in the future, and vaccine supply chains can be informed by Amazon success, manufacturing will always be in the hands of specialist companies.

Supply chain psychology. Key learning from the pandemic is understanding how supply chain stakeholders operated during this time. The buying behaviours of consumers impacted negatively on some supply chains. For others, panic buying meant businesses thrived as opposed to closing their doors. Surviving lockdown led to consumers buying more products than they normally would. Greater understanding of supply chain dynamics and consumer behaviours will strengthen supply chain design.

The pandemic has thrown a huge curve ball at our supply chains and caused chaos. This has been incredibly damaging for some businesses but has forced others to adapt and change, albeit painfully for many. In the same way that long COVID affects our patients, there may be a lag time in supply chains getting back to strength or a new level of normality. We have much to learn from how our supply chains performed during the pandemic, to reduce the impact of supply shortages of critical goods such as medicines and vaccines. The intelligence is waiting for us to mine and use it and there will be plenty more to follow. Let’s hope we use it wisely.

This article is part of a series on recovering from the pandemic in a way that makes societies more resilient and able to deal with future challenges. It is supported by PreventionWeb, a platform from the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Read more coverage here.