It will be some time in the early hours of Friday morning until we discover whether Newark will join the list of shock by-election results. But whatever the outcome, we doubt it will be as remarkable as the contest that took place 55 year ago in Earndale. An eventual Conservative victory by just 22 votes (after four recounts) the Earndale campaign was also noticeable for the burgeoning love between the Labour and Conservative candidates and for the fact that no sooner had the Conservative candidate been elected than his uncle’s death elevated him to the Lords voiding the result of the election.

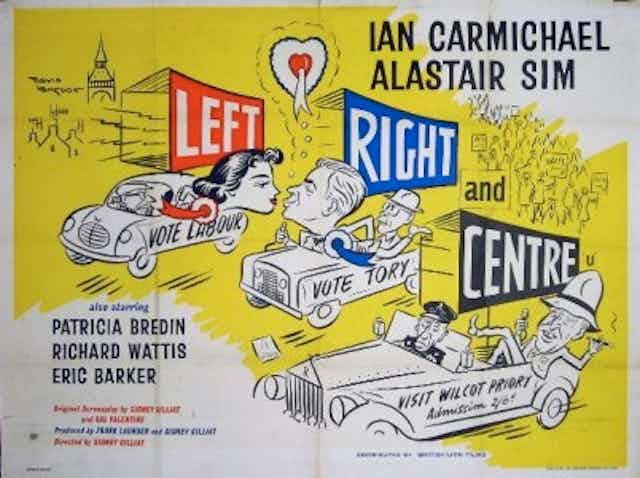

Earndale, of course, doesn’t exist. The by-election was the central plot of Left, Right and Centre, a satire/rom-com hybrid from Launder and Gilliet, best known at the time for their series of St. Trinian’s films. It is part of a long tradition of by-elections as a device in political fiction that stretches back to Dickens’ depiction of the Eatenswill election in the Pickwick Papers in 1836 to the parish by-election that is the catalyst for J K Rowling’s recent foray into “grown-up” literature in The Casual Vacancy.

Politics then…

The film itself was advertised with the tagline - “You’ll Howl When SEX and POLITICS Collide Head On!” – which could be said to have oversold it somewhat; it’s unlikely that anyone howled with laughter, even back then, and it’s a very 1950s take on SEX (which of course stands for LOVE rather than anything remotely raunchy). But still, the film survives as a revealing slice of political history.

That Left, Right and Centre is very much a film is of its time is at least superficially clear. A young Hattie Jacques plays a Labour campaigner, despairing of the destitution and poverty wrought by the Conservatives - whilst simultaneously being confronted by signs of widespread affluence, although in 1959 affluence was indicated by the profusion of TV aerials rather than satellite dishes.

And now…

The fictional by-election is also remarkable as it is a straight fight, with just two candidates. Newark boasts eleven which now seems unexceptional; in 2008 in Haltemprice & Howden there were 26 candidates crowding the ballot paper. And, to be expected, it’s a good deal cleaner than more recent examples of fictional takes on politics: there’s no top-quality swearing, no 1950’s equivalent of Tucker’s Law. Yet, in terms of substance, the themes touched on in the film deals are distinctly contemporary.

There are carpet-bagger candidates, desperately pretending to be local. There’s the issue of women in politics, the Labour candidate (played by Patricia Bredin, who just two years before had become Britain’s first entry in the Eurovision Song Contest), who is condescendingly cast as the “Girl for you”, even on her own party’s literature. There are the party activists, feeling unloved by the leadership: “We’re the ones what gets ‘em in”, complains the Labour agent. His Tory counterpart replies: “Not that it is ever appreciated”.

There’s the bumbling efforts of TV celebrities who fancy (and are encouraged to by a media-savvy party machine) trying their hand at politics. The Conservative candidate (played by Ian Carmichael) is characteristically a bit of an upper-class twit most famous for his role on a panel game. Announcing his candidature, the best he can manage is: “If one has something to offer then one ought to offer that something, whatever that something may happen to be.”

Machine politics

Very notable too is the dominant role played by manipulative party apparatchiks. Agents, rather than spin doctors in those days, but just like Malcolm Tucker today marshalling bumbling politicians and setting the agenda. Once love blossoms between the two candidates they do their best to stamp it out, and to engineer conflict. “It’s horrible”, complains the Labour agent. “If we was all to behave like this what would happen to parliamentary government?”

But above all, Left, Right & Centre (its very title all-encompassing) is pervaded by a sense of widespread political apathy and a soggy, consensus politics – the parties appearing so similar that it is impossible to tell them apart. From the point where the two candidates meet on the train, and order the same breakfast (“We seem to have the same ideas”, says Carmichael), to a lovely set piece in which there is a mix up over meeting venues, and the Conservative party bigwig delivers the same platitudinous speech (“Let’s keep strong, and look after the old folk”) to both parties – no-one notices, and he receives a standing ovation at both venues – the film plays up the extent to which the occupation of the centre ground leads to a bland politics of consensus and agreement, a childish playing up of minor differences, and a deadening of political discourse.

Plague on both your houses

From the very outset the film displays all the negativity and cynical tropes of representations of politics and politicians that are so familiar today but that can be traced back to Shakespeare. The animated title sequence even ends with a wall upon which are scrawled the words from Romeo & Juliet: “A plague on both your houses”, itself the title and epigraph of an earlier novel on politics written by Philip Gibbs in 1949.

This is followed by a world-weary narration that suggests that the electorate get the politicians they deserve – and it’s an electorate that the film also makes clear does not deserve very much. Apathy prevails, like today people are portrayed as obsessed with celebrities and low-brow culture. The film proceeds to show us bickering party managers, limp and windy politicians and above all a sage defeatism about the point of politics, with politics depicted as a game of, and for, its practioners. A politics devoid of real issues or debate, and of little interest or concern to anyone else. In all of its 89 minutes, there is not a single positive reference to politics or politicians.

Left, Right, and Centre may not be the greatest film in the world (though the one review on Amazon which begins with the words: “Not Very Good…” is a bit harsh). But anyone who thinks today’s politics – and complaints about it – are somehow original should be chained to a chair and made to watch it on a loop until they scream their repentance.